Angels on trial

The first attempt by the U.S. Department of Justice to bring a significant criminal case against the Hells Angels in the Pacific Northwest unfolds Monday in a heavily guarded federal courtroom in Seattle. There, federal prosecutors will ask a 12-member anonymous jury selected two weeks ago to convict Spokane’s Richard “Smilin’ Rick” Fabel, West Coast president of the Hells Angels, and three of his cohorts of racketeering.

The extraordinary step of identifying jurors only by number was taken, authorities say, to reduce intimidation – a hallmark of so-called outlaw motorcycle clubs that boast their members are so tough they are the “1 percenters” of society.

The trial is expected to last 10 weeks and involve up to 200 witnesses, many of them from Spokane and Eastern Washington. The case involves alleged acts of witness intimidation in Spokane and elsewhere, according to court documents.

The charges are included in a federal indictment brought under the Racketeering Influenced Corrupt Organization (RICO) law. It accuses Fabel, 49, and his Spokane-based motorcycle gang of running an organization that engaged in extortion, robbery, kidnapping, threats, drug-dealing, trafficking in stolen motorcycle parts and murder.

Convictions could send the defendants to prison for life.

The indictment – originally brought 13 months ago and modified five times – outlines 19 counts, charging Fabel and co-defendants Rodney Rollness, 45, Joshua Binder, 31, and Ricky Jenks, 29, with racketeering and a continuing conspiracy that began in 1996.

Rollness, of Snohomish, Wash., and Binder, of North Bend, Wash., also are charged with committing a violent crime in aid of racketeering: a killing in 2001 in Snohomish County.

Fabel faces the Seattle trial after similar federal charges against him were dismissed late last year in Nevada. Fabel and Jenks are still Hells Angels; Binder and Rollness are former members.

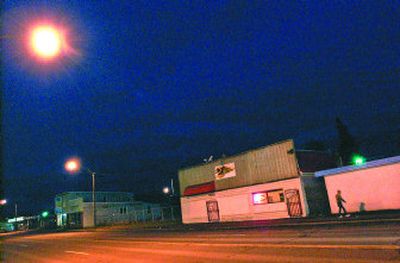

As part of the indictment, prosecutors in Seattle are seeking forfeiture of the Hells Angels’ Spokane clubhouse at 1308 E. Sprague Ave. Fabel’s name is on the deed to the property – a landmark of sorts that’s been the target of repeated police raids.

The clubhouse and a previous one at 1818 E. Third Ave. have been home base for the Hells Angels since the club first established its presence in Spokane and the Northwest in 1994. The club – officially called the Washington Nomad chapter – has drawn members from throughout the state for what are called church meetings, usually on Thursdays. Only members and their associates are allowed inside.

Conspicuous since arrival

Experts believe the Hells Angels chose Spokane because of its proximity to the Canadian border. The club has 227 chapters in the United States and 29 foreign countries, and an estimated 2,500 members.

The Hells Angels have been anything but low-profile since their red-and-white colors and signature death skull logo began showing up in Spokane 13 years ago.

A year after the Spokane clubhouse opened, the chapter’s then-secretary was arrested in December 1995, accused of killing a member of the rival Ghost Riders in a Hillyard bar. The Hells Angels member claimed self defense and was acquitted the following year.

In 2000, as Fabel worked his way up through the Hells Angels hierarchy, he organized the biker club’s annual national gathering in Missoula and posed for pictures with Ralph “Sonny” Barger, the club’s founder-turned-author. The bikers were largely peaceful in Missoula, but a group of townsfolk objected to a heavy police presence and got involved in a small riot with officers.

In 2001, Jenks and a man considered a club associate were arrested in the shooting death of a man making methamphetamine in a Spokane Valley home. Investigators determined the killing occurred during a drug rip-off.

Jenks later pleaded guilty to second-degree manslaughter and was sentenced to 21 months in prison. Not long after he was released, Jenks was arrested in connection with the racketeering indictment in Seattle.

‘A lot at stake here’

The trial, expected to last into May, will be built around evidence seized by federal and state investigators during a series of raids at the clubhouse and Fabel’s Spokane home.

Evidence taken in the raids, including copies of written rules and regulations for the Hells Angels, will be introduced as evidence to “prove the structure, common purpose and continuing existence” of the Washington Nomads as a racketeering enterprise, the government trial brief says.

The Justice Department has used the tough RICO law in the past to go after the Hells Angels, but not all of the prosecutions were slam-dunks and many ended with plea bargains instead of trials.

In the most recent racketeering cases, plea agreements were struck against Hells Angels in 2005 in San Diego and in 2006 in Illinois. The former Chicago president of the Hells Angels received the longest sentence, nine years.

“I don’t see this case as rendering any death blow to the Washington Hells Angels, but it is an important step in going after organized criminal groups,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Mike Lang, one of three Seattle-based prosecutors handling the case.

The Hells Angels, he said, “have been around long enough and they have enough members so they can continue operating in the Northwest even if the defendants in this case are convicted.”

The prosecution intends to introduce more than 1,000 exhibits, Lang said.

In an attempt to prove trafficking in stolen motorcycle parts, federal prosecutors hope to wheel into the Seattle courtroom a customized Harley-Davidson owned by Fabel that was taken during a Spokane raid.

Court documents also say federal prosecutors will attempt to show the jury four other Harley-Davidson motorcycles that allegedly were built with stolen parts and have altered vehicle identification numbers.

Fabel has been in custody at a federal detention facility in Des Moines, south of Seattle, since his arrest in Spokane in February 2006. In previous interviews, he would only grin when asked how he got the nickname “Smilin’ Rick.”

David Miller, acting U.S. marshal for the Western District of Washington, last week said the “high profile, high security trial” will take place in a courtroom protected by federal marshals and double metal detectors.

“There’s a lot at stake here,” Fabel’s court-appointed defense attorney, Peter Camiel, said a few days ago. “He’s facing the possibility of life in prison if he’s convicted.”

Attorneys for the other defendants didn’t return telephone calls seeking comment.

Fabel is “holding up well” and hopeful of being acquitted on the racketeering charges, Camiel said. The attorney wouldn’t say if Fabel will take the stand in his own defense.

‘Just another business day’

The racketeering indictment against Fabel and the others was returned Feb. 8, 2006, in Seattle, just four months after he was indicted in Las Vegas. The Nevada indictment accused Fabel of being one of the masterminds behind a bloody 2002 shootout in a Laughlin, Nev., casino involving Hells Angels and their rivals, the Mongols. The shootout left three bikers dead.

Fabel was accused in Nevada of 19 counts of violence in aid of racketeering and 13 counts of carrying a firearm during and in relation to a crime of violence.

The Nevada case, brought under the federal Violent Crime in Aid of Racketeering law, accused him and 41 other Hells Angels of operating a Mafia-like criminal enterprise that was responsible for the riot in the Nevada casino.

All the Nevada charges against Fabel and 35 other defendants were dismissed last fall after the government’s case began to fall apart, ending with plea bargains from only six of those initially indicted.

Fabel was out on bond on the Nevada charges, living in his modest home near Albi Stadium in northwest Spokane, when he was arrested on the racketeering indictment returned against him in the Western District of Washington.

Former Hells Angels infiltrator Anthony “Tony Uno” Tait, who testified as an expert witness in the 1995 Hillyard shooting trial, said the outlaw biker club views such criminal trials “as the cost of doing business” and that it won’t put a significant dent in their operations.

“It’s just another business day for them,” Tait said. “They got caught, so now they have to answer.

“If the feds can prove the RICO and they are convicted, it will be one of the first racketeering convictions against the club. They’ve tried to RICO them before, and it’s fallen through the crack every time.”

Tait, who keeps his whereabouts secret, previously provided information to the FBI about the Hells Angels, including their operations in Alaska where Fabel joined the club.

“He’s not the ultimate player in the gang, but then again he’s got a lot more clout than the average member,” Tait said. “He’s a pretty good fish – one you shouldn’t throw back in.”

Tait won’t testify in Seattle, but an agent with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms & Explosives who infiltrated the gang is scheduled to be called as an expert witness for the prosecution.

‘I’m scared’

The jury also will hear and see grisly evidence about the July 2001 shooting death of Michael “Santa” Walsh near Arlington, Wash. A separate trial was ordered for a fifth defendant, Paul Foster, 50, of Arlington, a former Hells Angels associate who is charged with being an accessory after the fact in Walsh’s death. Investigators say Walsh falsely claimed to be a member of the Hells Angels and was slain in an act that earned the killers a “Filthy Few” patch – a top honor only given to members who kill for their outlaw club.

The indictment accuses Rollness, Binder and “others known and unknown” of killing Walsh.

His bullet-riddled body was found in a roadside ditch on July 25, 2001, four days after he disappeared while attending a bikers party at Foster’s home in Western Washington.

The initial tip to police came about 11:30 p.m. on July 21, 2001, when a 911 operator received a call from an anonymous woman who reported hearing gunshots from a house near her semi-rural home near Arlington. The woman, who wouldn’t give her name and drove several miles because she didn’t have a phone in her home, said the shooting occurred at a house during a party.To help make their case about the fear factor surrounding such cases, court documents say prosecutors want the jury to hear the 911 tape where the woman caller says, “I’m scared. I’m scared of those people.”

To avoid prejudicing the jury, prosecutors will be barred from calling the Hells Angels a “gang,” and will only refer to the organization as a “motorcycle club.”

The connection to the unsolved murder of Walsh developed while police in Monroe, Wash., were investigating stolen motorcycle parts – an investigation that eventually involved the FBI.

Trial offers inside look

Tom Hillier, a former Spokane County assistant public defender who is now the federal defender for the Western District of Washington, said prosecutors are up against some of the best criminal defense attorneys in Seattle. Hillier is not directly involved in the case.

“They’re all really good lawyers, excellent criminal defense lawyers,” Hillier said. “None are flamboyant … just hard-working, skilled, creative trial attorneys. It’s a great defense team.”

Robert S. Lasnik, the chief judge for the Western District, will preside over the trial. The federal judge is a former King County deputy prosecutor with a reputation for being a “bright, capable, experienced jurist,” Hillier said.

“He’s not going to be controversial in the least,” Hillier said. “He’s not the sort of judge who’s the center of attention. He’s going to preside over the case with skill and dignity.”

Tait, the former infiltrator, said the Seattle racketeering case should give a public glimpse into the club’s methods of intimidation and how the Hells Angels established a beachhead in the Northwest.

“The Angels pull stuff off and get away with it because the fear is so great,” Tait said. “They don’t have to worry about sticking a gun in somebody’s mouth and having them call the police. That victim knows, ‘The next time I may not live through it.’ “