The rush of the river

They don’t want to end up like the dog.

Kayakers know the story: Years ago, a few boaters came across a canine that ended up “wavekill.”

Don’t worry; the poor pooch’s legacy lives on.

Dead Dog Hole, as it is so aptly named, is one of five kayaking playspots on the Spokane River, along with Corbin Park, Mini Climax, Sullivan Hole and Trailer Park Wave, which is named for its proximity to – you guessed it – a trailer park.

The not-so-animal-friendly name intimidated Chris Hoffer at first, but the section of the river near the state line quickly became man’s best friend. Dead Dog Hole is formed by a large, angular slab of rock, making it a prime spot for learning new tricks, said 38-year-old Hoffer from Post Falls.

“It’s the never-ending surf wave. You can stay in one spot in a controlled environment (on the river),” he said. “It’s like skiing fresh powder, like getting fresh tracks in every single ride.”

Sullivan Hole, which is one of the most popular playspots, is a “trusty dog,” (as opposed to a dead one) said Daniel Henry, a 32-year-old kayaker from Coeur d’Alene. Fellow kayaker Travis Nichols prefers paddling Trailer Park Wave.

“(Trailer Park Wave is) the most dynamic,” said Nichols, 24, who started kayaking four years ago and is a sponsored boater. “You can do a lot of different varieties in tricks. And when I say dynamic, I mean it has the most energy potential.”

Hoffer, who has been kayaking for nine years, said when he saw his friend’s inflatable boat it was love at first sight.

“I knew I was gonna start kayaking before we even touched the water,” Hoffer said. “I had called my bank and already had a loan.”

Terry Miller’s love story is similar to Hoffer’s.

“I just got hooked,” said Miller, president of the Spokane Canoe and Kayak Club. “Being on the river – it’s like a religion.”

And it’s an easy religion to practice with so many rivers and creeks close by.

“You could spin the compass in any direction,” Nichols said. “We’re right at the center of lots of great resources.”

Although kayakers in the Inland Northwest have access to rivers in Washington, Idaho, Montana, Oregon and Canada, some boaters long for adventures in uncharted waters.

Miller, who just returned from a month-long kayaking trip in New Zealand, doesn’t kayak for an adrenaline rush. He gets his high from conquering the unknown.

“For us it’s just about scouting a rapid, seeing a line in your head and being able to make it,” Miller said. “It’s more of a challenge.”

A sprinkler sales manager during the summer, Miller kayaks the world in the installation off-season. He has creek boated rivers in Argentina, Chile, Buton and Nepal.

“Doing the multiday descents in Nepal was awesome because you got a raft that’s carrying all your stuff with sherpas, and the monkeys and everything come out at night,” Miller said.

“Buton is the last Buddhist kingdom in the world. In New Zealand you could get a helicopter there in an hour, but in Buton it would take two weeks.”

No matter where these kayakers decide to dip their paddles, safety and know-how come first. Before hitting the river kayakers should take lessons, Nichols said.

“I started by learning through structured, organized lessons and removed years of bad habits,” he said. “Lessons are the best place to start because they can get you going in the right direction.”

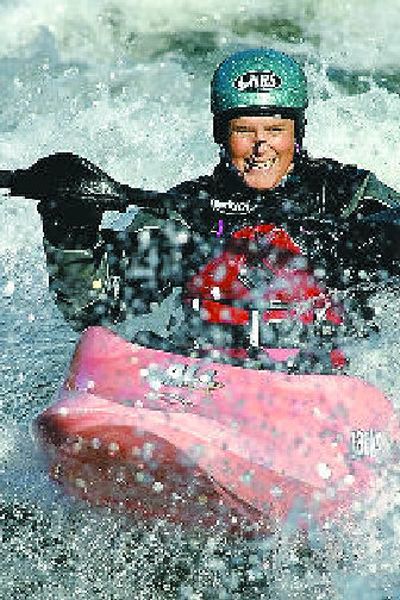

As for safety, Hoffer has learned a few things over the years – some the hard way. Rule No. 1: Buy a helmet that fits.

“It was my first four months of kayaking, and I didn’t realize the importance of a good-fitting helmet,” he said.

“I was at the North Fork of Clearwater River, and I flipped upside down in a rapid, and my helmet exposed my forehead, and I hit a rock.”

The result was a concussion, nine stitches and a broken nose.

A week later he was back at it. Hoffer removed his stitches himself and set out on the Priest River in northern Idaho.

“But I only did one run and everyone else did two,” Hoffer said, laughing.

While Miller doesn’t have any horror stories, he said he always goes home with a few bumps and bruises, maybe even a bloody nose now and then.

“I’m sure if we were younger we’d be pushing the envelope more,” he said, “but there’s always a job to go back to Monday morning.”

Despite the injury stories and pictures of extreme kayakers sailing down 20-foot waterfalls, the sport is not only for thrill-seekers.

“Whitewater kayaking is a sport for everyone,” Nichols said. “It’s one of the most misunderstood sports. Danger is a part of the sport, but the bigger part is just finding a group of people and getting out there. I’ve boated with 10-year-olds and 90-year-olds on the same part of the river.”