As Bonds closes in …

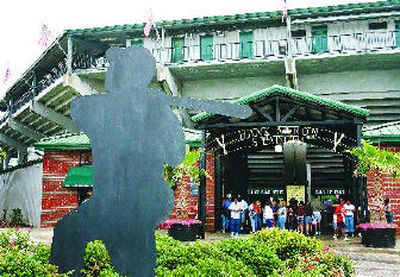

MOBILE, Ala. – Charlie Lord stands at the entrance to Hank Aaron Stadium, under a giant baseball emblazoned with the famed “755” and facing a life-sized cutout of Mobile’s most famous son.

He knows it’s only a matter of time before Aaron’s home run record falls to Barry Bonds and the shrine loses a bit of its shine.

Then, Mobile no longer will be known as the hometown of the home run king.

“I think a lot of people here would like to see Hank Aaron hold the record forever,” Lord says, “and a lot of them just say it’s part of life.”

Residents of this Alabama port city, like many baseball fans, have mixed feelings about the imminent fall of Aaron’s record to Bonds – and about the man himself, who has long lived in Atlanta.

There are tributes, such as the minor league stadium named for Aaron. And the sprawling Henry “Hank” Aaron Park, featuring a granite statue of the slugger not too far from Hank Aaron Loop, which circles downtown.

He’s the centerpiece of displays featuring the city’s five Hall of Famers at the stadium and park – Satchel Paige, Ozzie Smith, Willie McCovey, Billy Williams and Aaron.

Lord, CEO of the local YMCA, praises the dignity Aaron has brought in his occasional visits to speak to kids.

Others grumble, claiming he has kept his distance from Mobile residents during trips back and even citing a canceled visit for the Double-A Mobile BayBears’ opening night because of a scheduling conflict.

Idella Lane doesn’t want to hear such talk, or criticism of Aaron, who has said he doesn’t plan to be present when Bonds breaks the record.

“He doesn’t owe Mobile anything,” the retired nurse said during a recent BayBears game. “I think the press is awful the way they’ve dealt with him.”

She attended high school with Aaron’s late brother, Tommie, also a former major leaguer. Lane met the older Aaron only once, when his sister helped organize a trip to Atlanta for a Braves game.

He showed up at the hotel “and everybody hugged him,” she said.

Aaron didn’t play baseball at Central High School or Josephine Allen Institute, which he attended his senior year. Those schools didn’t have baseball programs.

Aaron’s discovery came during a neighborhood softball game. Ed Scott, then a scout for the Negro American League’s Indianapolis Clowns, spotted him hitting line drives off the outfield fence.

“I was like, ‘Look at those wrists. Why isn’t he playing baseball?’ ” Scott recalled. He signed Aaron for the Clowns at $200 per month and took a photograph of the future star at the train station wearing a suit. That photo still hangs in Scott’s home.

And now that Bonds is catching up to the 33-year-old record?

“I hate to see it be broken, but records are made to be broken, you know?” Scott said. “Somebody’s got to break it. It’s been a good while.”