Valley man swept up by chance to help

Darrin Coldiron is no stranger to taking the long way home.

In 2005, he left a good paying job with the Spokane Valley Fire District and set off for tsunami-ravaged Sri Lanka to search for a college friend he feared was lost among thousands killed when a massive wall of water hit the day after Christmas 2004.

It turned out his friend was OK, but that journey more than two years ago taught the firefighter a valuable lesson: A helping hand can be grabbed by anyone. His journey took him to Komari, a village of 3,000. More than 95 percent of the coastal town had been wiped out by a wave more than 25 feet tall. Many residents were swept out to sea.

Coldiron felt a kindred spirit for the town when he first saw it. It was small enough to be all but forgotten by the other relief organizations in the area, but the right size for a couple of volunteers to make a difference.

Sri Lankans feared the tsunami would strike again and didn’t want to return home.

Coldiron and another volunteer, firefighter Nick Muzik, decided they’d be the first people to return to flattened Komari. They rented one of the few buildings left standing, then started cleaning up properties and forming construction crews of local residents to rebuild the town. Working with others, they formed their own, homespun nonprofit Community Focused Disaster Response, or CFDR.

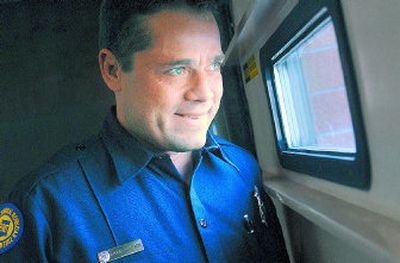

After spending about 18 months of the last two and half years in Komari, Coldiron returned to Spokane Valley in late April. Last week, he was at the fire district headquarters, brushing up on his emergency procedures so he could once again go out on call.

He is, to say the least, a changed man, the kind of guy who shrugs his shoulders at the thought of selling his home and leaving his job to help someone else. He smiles when explaining the decision and utters words few of us ever say.

“It’s only money,” he said.

He might still be in Komari today were it not for an ethnic war between rebels of the island nation’s Tamil minority and the Sinhalese government. The fighting between the government and a faction of Tamils who want their own state has driven hundreds of relief workers out of the island nation in the past year. Aid workers in other parts of the country have been killed. Not long after Coldiron set off for his third Komari trip last June, the New York Times reported that 17 workers for the relief group Action Against Hunger had been shot execution style in their office. As a result of the violence, only a third of the homes promised to tsunami victims had been built in areas of the country plagued by fighting.

“It’s like crossing a fast moving creek with slick rocks,” Coldiron said of the challenges associated with living with the likelihood of deadly violence. “Every step has to be planned ahead.”

His group had to send a couple volunteers home because they just weren’t cautious enough. Bullets were flying in Sri Lanka roughly a year after the tsunami. Air raids, jungle clashes and suicide bombings have killed at least 4,000 people since then, according to U.S. State Department estimates. The fighting wasn’t affecting Komari for the first year Coldiron’s group was there, but the violence crept toward town.

Last year at this time, the Sri Lankan government’s special task force had been attacked inside Komari by unidentified gunmen, which in turn led to villagers being searched daily at gunpoint for identification. Children on their way to school had their bags searched at gunpoint by government soldiers, and checkpoints that had been routine and civil since 2002 became a cause for fear.

For CFDR, there were no sides in the war, Coldiron said. All they wanted to do was help a village mend. Even now, more than a 30-hour plane ride away from Sri Lanka, the firefighter is guarded about what he says about the fighting, because he doesn’t want a Tamil fighter or some government official surfing the Internet to read his comments and retaliate against Komari villagers.

However, Coldiron does say Komari is in a war zone. One of the things that seldom shows up in the 10-second video clips of war anywhere on the nightly news is that there are a lot of people caught in the fighting who just want to get by, and the only side they really take up is the side of life. But even life can be a hard cause for some to champion; Komari has one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

The hope of CFDR is that it has made odds for a successful life better. Before Coldiron left, the group had arranged to have skilled tradesmen come to the village and teach Komarians the basics of electrical wiring and plumbing. The group created education seminars to prepare Komarians for placement in the final grades of the public education system. Komari farmers are experimenting with agricultural practices facilitated by CFDR.

But the group’s biggest influence on the village might be the creation of CFDR itself. Sometime this summer, the last American volunteer for CFDR will leave Komari.

The locals who have worked closely with the group for two and a half years will take over the program. They’re ready, Coldiron said. Komarians have sharpened their use of the English language and more importantly their understanding of bureaucracy behind the international relief world. Already locals working with CFDR have learned what it takes to negotiate contract work with nongovernmental organizations. The locals have become a contractor of choice for reconstruction efforts. That’s a big difference from where the community was in January 2005 when Coldiron arrived with fellow firefighter Muzik. Civil war between the Tiger militia of the minority Tamils and the army of majority Sinhala government has left Komari with no leadership. Living in fear, it was safer to do nothing.

CFDR’s promise to the Komarians is that it will continue to sponsor the programs started by the group for another five years. If the money needed to back up the pledge comes from American donors, so be it. If the donations quit coming as Americans forget the tsunami of 2004, Coldiron said he and others – in order to keep their word – will put their life savings into the project. And maybe with a successful outcome, the group of friends can turn their attention to another village in another country in need of a helping hand.

“There’s a lot of water between here and there,” said Coldiron. “We have to wrap up Komari first.”

Then again, all it took the first time was a plane ticket and a willingness to help.