Development draws criticism

A 700-acre commercial and residential development at Liberty Lake, advancing under the banner of economic development, looks like “the attack of the real estate developers” to Otis Orchards resident Edward Hojnowski.

“They want us to pay for it, and they walk away with a profit,” Hojnowski told Spokane County commissioners.

Hojnowski was among several Otis Orchards residents who testified earlier this month against a proposal to create a “revenue development area” that could give developers up to $50 million in sales tax revenue over 25 years — on top of an estimated $15 million from local property taxes.

The principal companies to benefit from this public spending would be Jim Frank’s Greenstone Corp. and Centennial Properties, a subsidiary of Cowles Co., which owns The Spokesman-Review.

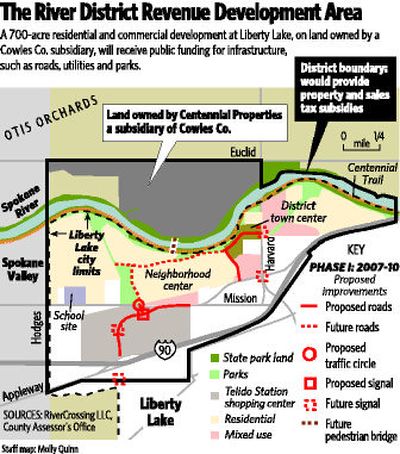

Centennial Properties has teamed up with Greenstone — as River Crossing LLC — to develop 700 acres of Spokane River frontage north of Interstate 90 on both sides of Harvard Road.

Frank said Greenstone is managing the project, while Centennial Properties’ role is to sell land under an option agreement as the development progresses.

Greenstone will develop about 700 acres on the south bank of the Spokane River in a mixed-use project called the River District of Liberty Lake. The project will get tax support from a 1,200-acre “revenue development area.”

The revenue area includes some 200 south-bank acres that aren’t part of Frank’s project. Owners of that property, including auto dealerships and other existing businesses, also may apply for property tax and sales tax assistance.

Frank said the revenue development area also includes approximately 300 acres on the north bank, mostly owned by Centennial Properties, but he has no plan to develop that land.

River District plans call for a shopping center called Telido Station, a business and office park, 1,320 apartments, 1,355 townhouses and 2,470 single-family homes. Greenstone specializes in large residential projects while Centennial Properties is a land company that does no development on its own.

Centennial was not involved in development of the River Park Square shopping mall in downtown Spokane, which is controlled by companies affiliated with and owned by Cowles Co.

Unlike River Park Square’s complicated and controversial public-private financial partnership, River District will get a straightforward public subsidy.

However, Frank said his project won’t use any public money for work that ordinarily would be required of developers, such as residential streets. Instead, he said, the money will be used only for “core infrastructure” — such as arterial streets, water reservoirs and parks — that ordinarily are provided by local governments.

Much, if not all, of the money is to come from increased sales and property tax collections generated by development within the 1,200-acre revenue area.

The area encompasses both a “tax-increment financing” system, or TIF, that was established in December 2005 and the Local Infrastructure Financing Tool, or LIFT, that county commissioners are poised to implement on June 19.

The TIF diverts 75 percent of future property tax collections to developers for 15 years, excluding taxes for schools, bond debt, excess levies and taxes that are limited to a single purpose. Emergency medical levies and Spokane County’s conservation futures levy are examples of single-purpose taxes.

River District home construction is under way, and the TIF generated $89,870 this year in its first annual collection. The revenue is expected to increase substantially next year.

The state of Washington will pay up to $1 million a year for 25 years under the LIFT program, to be matched by another $1 million a year from the city of Liberty Lake.

Spokane County will administer the district and issue bonds to be repaid with money from Liberty Lake and the state. State law allows work to be done from cash flow for five years, but requires public bonds to be sold after that.

The county can be left holding the bag only if county commissioners abandon their pledge to require the developer or the city to back the bonds with a binding line of credit. Liberty Lake, in turn, has a contractual right to decide all use of the tax money.

Little vocal opposition to the River District project had surfaced until a May 15 hearing on the development’s sales tax support. Then about a half-dozen Otis Orchards residents waited more than four hours to tell county commissioners they don’t want urban development in their semirural area across the Spokane River from Liberty Lake.

“I’m not in Liberty Lake,” Carole Stansberry said. “Liberty Lake is the rich people on the other side of the river. We are the redheaded stepchildren.”

She and others complained about lack of notice, and Frank apologized for failing to contact Otis Orchards residents.

“It never occurred to us to talk to this neighborhood,” Frank said. “We have no plan to develop this area.”

Centennial Properties Vice President Bob Smith said “economics will drive everything,” but the company has no immediate plans for the north bank land.

“That’s so many years out that I probably won’t be alive by that time,” Smith said. “You’re talking about something that could be 15, 20, 25 years out.”

Frank said the north bank area was included in the TIF and LIFT district for the sake of long-range sewer planning. The Liberty Lake Sewer and Water District has excess capacity and is willing to serve the north bank.

“We’re just ready for the future,” sewer district Director Lee Mellish said.

Frank said Liberty Lake is a “wonderful community” and has a “fantastic light industrial base” because leaders had the foresight to build the infrastructure necessary to attract Hewlett Packard and other high-tech companies.

Indeed, said county Treasurer Skip Chilberg, “Liberty Lake is one of the hottest development areas in the county.”

That’s why he thinks no public development incentives are needed.

“We divert funds to developers and then we have to go back to the taxpayers when we need money for mental health, and there is something wrong with that picture,” Chilberg said, calling mental health one of “a lot of other examples.”

In December 2005, county commissioners imposed a three-year, 0.1 percent sales tax increase, effective last June, to pay for mental health services. The tax will raise about $7.5 million in its first year.

Frank countered that failure to provide more ready-to-build sites cost Liberty Lake a Cabela’s sporting goods superstore and a Sysco Foods distribution center, both of which decided to build in Post Falls.

“Both of those projects were lost because Idaho was more foresighted in having infrastructure and pad sites available,” Frank said.

County Commissioner Bonnie Mager shares fellow Democrat Chilberg’s view that solid developments would be built even without public assistance.

Both of them cited developer Marshall Chesrown’s Kendall Yards as a project they think is being subsidized unnecessarily.

Chesrown plans up to 2,600 residential units and 1 million square feet of retail and office space on the north bank of the Spokane River, west of Monroe Street.

The Spokane City Council voted 6-1 to give an estimated $20 million to $25 million in future property taxes to Kendall Yards. County commissioners earlier agreed to participate in the subsidy, but Mager dissented on grounds that the decision was rushed to accommodate a groundbreaking ceremony.

Mager has the same complaint about the River District sales tax decision. She wanted to continue the recent hearing to investigate the complaints of Otis Orchards residents, but any delay in the tight timetable would cause a year’s delay in revenue collection.

Commissioners had to close the River District public hearing to allow a 30-day waiting period before making a decision on June 19. Legislators eliminated the waiting period after the River District LIFT request was filed, and lawyers advised commissioners to stick with the old rules.

Mager applauded Frank’s plans for low-income housing and environmentally sensitive amenities, but said she thinks publicly subsidized projects need more scrutiny.

“I see us just being bombarded by requests under the name of economic development — and maybe it is, and maybe it isn’t,” Mager said.

Instead, she said, public officials should identify needs, set goals and accomplish them with incentives to developers.

“Where is the legal mechanism to make sure you can hold the developers’ feet to the fire?” Mager added, citing a tax-subsidized project on the West Plains that promised a biomedical park and delivered a hotel, a restaurant, a bank and a travel agency.

Republican County Commissioners Mark Richard and Todd Mielke rejected Mager’s assertion that the county’s economic development cart is ahead of the horse.

“I don’t believe government is in the development business, so I don’t believe government comes up with the projects and then asks developers to come forward and do the job,” Mielke said. “I think we need to go by what the law says.”

Richard agreed that waiting for proposals from developers is “exactly the way the Legislature intended it to happen.”

In the case of River District, the Legislature actually chose the project as a demonstration of the new LIFT sales-tax incentive program, Mielke said. The program grew out of competition with Idaho to attract Cabela’s, he said.

Kent Hull, whose Iron Bridge office development in Spokane was approved by the Spokane City Council for property tax subsidies, said he thinks projects in urban areas offer community benefit while those on bare land in outlying areas promote sprawl.

“I really would like to see it used more for revitalization,” Hull said of programs such as TIF and LIFT.

Frank thinks both kinds of development deserve public support.

Without open land in places like the River District, “where else do you have enough land for things like Telect, Itron or Microsoft, for that matter,” Frank said, referring in general terms to the high-tech industry that has settled in Liberty Lake. Sen. Chris Marr, D-Spokane, said subsidies should be aimed at “unique economic development opportunities.” Big box developments with stores like Wal-Mart shouldn’t qualify, he said.

But Marr said he approves of the River District project and a couple tax-increment financing districts county officials have established in the West Plains.

State law requires tax subsidies to be spent on streets, sewers, parks and other public infrastructure. River District infrastructure spending is expected to total $72 million, including $16 million for a new Liberty Lake interchange on Interstate 90.

Greenstone spokesman Jason Wheaton said River District plans also call for spending $21.6 million on basic street and utility improvements, $2.5 million for transit parking and $2 million for wastewater reuse. A network of underground pipes would allow use of treated wastewater for park and open-space irrigation.

Plans call for nearly $30 million to be spent on parks, trails and other recreational improvements, including a $5.8 million sports complex.

“We think it’s just a wonderful opportunity to enhance the Centennial Trail and to enhance the trail system in Liberty Lake,” Frank said.

Businesses planning to expand or relocate look for areas that have amenities and infrastructure in place, he said.

According to Business Planning Consultants of Spokane, River District will cost nearly $1.1 billion and create 9,877 jobs. The consulting firm also forecasts the project will generate $30 million a year in property taxes, $17 million a year in sales taxes and $1 million a year in real estate excise taxes, Frank said.

Like the state’s share of the $2 million-a-year LIFT contribution, Liberty Lake’s share may come from increased sales tax receipts in the development district. However, the city could use money from any source; other possibilities include contributions from developers or transportation mitigation fees the city has been collecting from developers since 1994.

Liberty Lake Community Development Director Doug Smith said officials will decide how to provide the local match after getting a better idea of how much tax money River District can generate.

State law would require Spokane County to issue public bonds for the district within five years of its creation.

“I’m just a firm believer that this is not only legitimate, but completely appropriate,” Richard said.

Staff writer Jonathan Brunt contributed to this report.