A goodbye for a friend

ELLENSBURG – A chimp act is a hard act to follow. You don’t have to tell Roger Fouts this. He has been following one for some 30 years.

But Monday’s memorial service for a very special chimpanzee named Washoe was the toughest act yet for the primate researcher and his family.

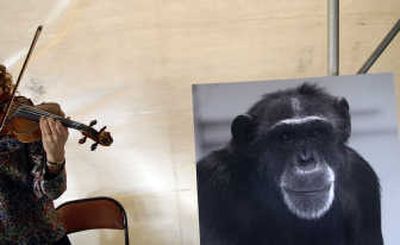

Nearly two weeks after Washoe’s death made news all over the world, those who knew her best gathered at Central Washington University to pay their respects. A cellist played a Bach suite as nearly 300 people crowded in and around a funeral tent outside the Chimpanzee and Human Communication Institute on the university’s Ellensburg campus.

Some wept as Fouts recalled not just what the chimp meant to him, but what she told him, as well.

Washoe, who died of natural causes at age 42, was the first non-human to use a human language, American Sign Language, and the first non-human to pass that language on to another of her kind – both considered groundbreaking achievements in their times. “We got to say goodnight to her,” Fouts said of the last moments he and his wife, Deborah, spent with their beloved friend.

Washoe, the matriarch of a chimpanzee family that has lived at the institute since 1980, was born in Africa in 1965. She was first acquired by University of Reno cognitive researchers Allen and Beatrix Gardner, with whom she lived in Washoe County, Nevada, until she was 5 years old.

As the chimp began to learn sign language, “very soon it was clear – or rather wasn’t clear – who was experimenting on whom,” Gardner said at the service Monday.

Washoe spent several years at the University of Oklahoma, where Fouts continued the primate research.

In 1979, after losing her own infant to pneumonia, Washoe was introduced to another young male chimpanzee as a way to assuage her grief.

“My baby, my baby,” Washoe signed that day, Deborah Fouts recalled. From that moment on, Loulis became Washoe’s adopted son.

Loulis quickly began to sign, including several words that the researchers did not teach him. He learned these words from Washoe.

Washoe had something to teach the Fouts children, too.

“Our children have never known life without Washoe in it,” Deborah Fouts said. When now-grown Joshua, Rachel and Hillary came home, Washoe would get very excited. “She would see them at Christmas and start screaming with joy.”

All three human siblings returned to Ellensburg for Monday’s service.

“I grew up with an incredible non-human sibling who taught me compassion for all beings,” Rachel Fouts said.

Deborah Fouts said there is still a great deal to be learned from the institute’s remaining chimpanzees, Dar, Tatu and Loulis, but the institute is not set up to introduce new chimpanzees into the close-knit family, which is reeling from the loss of Washoe. The institute offers educational programs for students of all ages. “She taught me that we are all beings,” Deborah said of Washoe in an interview. “Our beingness, human or chimpanzee, is the most important part of us.

“By any measure, Washoe’s life was extraordinary.”