Too good to be true

SAN JOSE, Calif. – Here are the morals of the Marion Jones story:

“If it seems to be good to be true, then it isn’t true.

“If you wonder why the media is a skeptical bunch, this is why.

“If anyone ever tells you he or she “thought it was flaxseed oil,” don’t believe that person.

Seven years after she stole our hearts, five medals and Olympic credibility, Jones finally admitted she was a thief. A cheat. A liar.

Jones, according to the Washington Post, has sent a letter to friends and family apologizing for doping and for disappointing them.

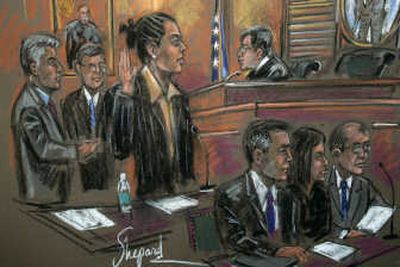

She pleaded guilty in U.S. District Court in White Plains, N.Y., to using performance-enhancing drugs and lying about it to federal investigators.

This news comes as a shock only to the folks who contributed to the Floyd Landis Defense Fund. Or the fans who say Barry Bonds is an innocent victim of a bitter media vendetta.

The confession has chipped the last fragment of gilt off the one-time golden girl. Erased the last trace of what was such a pretty picture.

The fallout remains to be seen. Jones might face lawsuits. She might be stripped of her five Olympic medals. The Justice Department might seek to charge more athletes, such as one currently unemployed home run king. Or it may be the end to the sordid story.

If you don’t remember how big Jones was in the summer of 2000, I can remind you. Because I was right there, mythologizing her every move. Yes, I feel stupid about it. And about the glowing accounts of certain soaring home runs I witnessed the next year. And about a certain degree of wide-eyed acceptance of lot of other amazing athletic feats I’ve witnessed during my sportswriting career – a career that has spanned the steroid era.

If Jones perpetuated a fraud on the American public, I – along with the majority of my colleagues – was her accomplice.

Jones made for fabulous copy. She was smart, stunning and media savvy. She smiled for the cameras, glammed up for magazine covers, set sky-high goals and almost reached them.

But the other lesson in the Jones story is that where there’s smoke there’s fire. That little puff of smoke in 1993 – which Jones attacked like a true professional, hiring Johnnie Cochran to defend her – was indication of the inferno that was to come.

Jones never learned her lesson. She associated with dopers her whole career. Even in the midst of her glory in Sydney, her then-husband C.J. Hunter was involved in controversy after reports revealed he had tested positive for steroids earlier that summer.

Along the way, as the accusations mounted, Jones continued to attack and deny. She filed a defamation lawsuit against BALCO Laboratories founder Victor Conte for $25 million. She held news conferences to insist she was clean. She had her high-priced lawyers and consultants conduct a relentless campaign to discredit reports, insist the true story hadn’t been told and hound reporters who questioned her version of events. She called the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency a kangaroo court. She was indignant, adamant, and lying every step of the way.

She was able to fool a lot of the people during that time. Anyone critical of the woman who had sullied the Olympic ideal and earned millions through her lies was accused of harassing her, of not understanding, of racism. Of, yes, carrying out a media vendetta. Even as the evidence mounted, plenty didn’t want to see it – only the pretty picture that had been painted once before.

Back in 2000, Jones seemed to have it all. Beauty, smarts, fame, medals.

And a body juiced on performance enhancing drugs.

The moral of the story? There’s nothing moral about this tale.