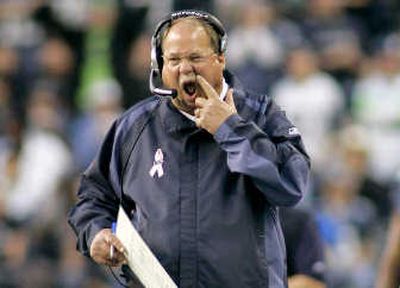

Cameras’ intrusion irks Holmgren

KIRKLAND, Wash. – The Seahawks almost disastrously found out the billion-dollar hand that feeds the NFL can also bite back.

Early in Seattle’s 28-17 loss to New Orleans Sunday night, the Saints called a timeout. As NBC went to a commercial and Matt Hasselbeck exited the huddle to confer on the sideline with Seahawks coach Mike Holmgren, the network’s overhead camera crashed to the turf near the startled quarterback.

“It was real close … I’m going to talk to my lawyer and get back to you,” Hasselbeck joked later.

After momentarily righting itself, the camera again slammed onto the field, near receiver Bobby Engram. Officials delayed the game for almost 10 minutes before the network got the camera away from the field of play, parking it directly over the Seahawks’ bench. Players stepped over themselves to avoid standing under it, as if it was a guillotine.

“Think of that,” Holmgren said. “Unbelievable.”

Later in the game, NBC’s more conventional sideline camera zoomed onto Holmgren’s play card. NFL coaches are so secretive about what’s on that, they commonly shield their mouths with it while calling plays just so TV doesn’t show them mouthing even a syllable of a call that is unintelligible to almost every viewer not named Bill Belichick.

But NBC’s shot was close so clear that anyone could read Holmgren’s plays from a living room couch.

“I don’t even know how they do that,” Holmgren said this week, sounding incredulous. “Was that the camera that almost hit Matt and killed him?

“There are not a lot of secrets. But those things they should probably tell you they’re going to try do that, or ask you. … I would rather they wouldn’t do that.”

Fred Gaudelli, producer for “Sunday Night Football,” said when the shot appeared on his 8-inch monitor in the production truck, he couldn’t read the plays. But when he and director Drew Esocoff aired the shot, they immediately saw on their 35-inch main monitor that it was too revealing. Gaudelli estimated they cut away after 1 1/2 seconds.

For years, Holmgren was on the competition committee, a mix of team owners, general managers and coaches who consider changes to the game. He said he was one of the only voices opposing some of the more intrusive innovations networks wanted to employ.

“The television executives would bring their proposals to the committee, about sideline reporters, about access to locker rooms,” Holmgren said. “The committee makeup changed over the years to the point where, at one point, I was one of two coaches on.

“It didn’t take me too long to figure out that the television people, really, because of the enormous amount of money that’s spent, they’re asking for an opinion from the competition committee, but really all they’re doing is saying, ‘Listen, this is really what we want to do.’

“They didn’t want to hear what I had to say most of the time.”

Gaudelli pointed out the good in the relationship TV has had with the NFL, dating to the 1960s.

“I think there is a proper balance to everything,” Gaudelli said. “But the success of this league is largely owed to television. It pays for the salaries of the players and the coaches – including all the people serving on the competition committee.”