Montana governor fetches attention

HELENA – “Get a dog.”

That’s the advice Montana Gov. Brian Schweitzer has for Idaho Democrats, who continue to be blasted out of the ballot boxes by Republicans.

Schweitzer was joking. Somewhat.

The first-term Democrat made the comment during an interview in his office last month. Lying on a pillow a few feet behind Schweitzer’s chair was Jag, the border collie ranch dog who trots behind the governor everywhere, including the marble halls of the Statehouse.

Even Schweitzer’s critics concede the dog was a brilliant political move: a populist mascot, of sorts, for a political party desperate to distance itself from the East Coast of John Kerry. Schweitzer, a dog-loving, gun-toting, death penalty-supporting, Arabic-speaking farm boy, was elected alongside a Republican lieutenant governor running mate in 2004 – the same year George W. Bush took the state by 20 percentage points over Kerry. Schweitzer is being eyed as a model for Democrats nationwide and has been mentioned as a possible vice presidential pick.

“Schweitzer is our shining star,” said Bev Moss, chairwoman of the Kootenai County Democrats. “It’s not the East Coast Democrat that appeals to people out here. It’s Brian Schweitzer carrying around his gun with his dog next to him.”

Moss admits that a Schweitzer-like candidate has yet to emerge in Idaho, but she hopes the growing popularity of Democrats in Montana will somehow spill west over the Bitterroot Divide. “Montana is very similar to Idaho, with that whole independent streak,” Moss said.

Schweitzer, 52, grew up in an Irish-Catholic household where a portrait of John F. Kennedy hung beside an image of the Virgin Mary. His parents never finished high school, but he went on to earn a master’s degree in soil science. Schweitzer then spent nearly a decade working on irrigation projects in Saudi Arabia – where he learned Arabic – before bursting onto Montana’s political scene during the 2000 election cycle with a campaign to unseat the state’s incumbent Republican senator, Conrad Burns.

“I never heard of him before; no one had,” said Charles S. Johnson, a veteran political journalist and statehouse bureau chief for Lee Newspapers, which publishes dailies in Billings, Helena, Butte and Missoula. Schweitzer lost to Burns by 4 percentage points, but “he never really stopped campaigning after that,” Johnson said.

After his defeat, Schweitzer traveled the state, taking his populist message to the smallest of small-town audiences, Johnson said. The national press took note as Schweitzer frequently hosted busloads of senior citizens to buy cheap pharmaceuticals in Canadian border towns.

“He’s just a bundle of energy,” Johnson said. “He’s probably the best retail politician I’ve seen in approaching people and talking to them.”

Schweitzer often repeats the story of speaking at the ceremony for a graduating class of one student. Republicans in Montana have taken to joking about the seemingly omnipresent Schweitzer, who never misses a chance to shake a hand.

“He’ll walk into a basketball game and assume it’s a party for himself,” said Bob Keenan, a longtime Republican lawmaker from Bigfork and former president of the Montana Senate. “He’s a really amazing politician in that regard.”

As Schweitzer was recovering from his failed Senate bid by shaking hands from Alzada to Yaak, the state’s Republican governor, Judy Martz, was floundering. She had famously proclaimed herself the “lapdog of industry,” and had become embroiled in a scandal after laundering the bloodied clothes of a top adviser involved in a drunken driving fatality. Martz’s approval ratings were typically in the 25 percent range, Johnson said.

In 2004, Schweitzer was elected, ending 16 years of Republican control. After his inauguration, he threw away the key to his office. It has remained open ever since, with journalists welcome to sit in on any meeting at any time.

Schweitzer also made news early in his term by calling for the return of Montana Guard troops from Iraq, speaking out against the Patriot Act and pardoning 79 deceased Montana residents of German heritage who had been found guilty of sedition during World War I for such offenses as praying in German or not singing the national anthem. Schweitzer’s German grandparents had been forced to kiss the American flag to show their loyalty, he said.

National energy independence has become the central goal of Schweitzer. “I know how dangerous it is to be dependent on foreign oil,” he said. “Our economy is dependent on dictators. … It’s the greatest peril to this country in the history of this country.”

While the governor was laying out his energy policy, Jag woke from a nap and began roaming the office. Schweitzer spotted the dog and snapped his fingers.

“Jag, would you lay down?”

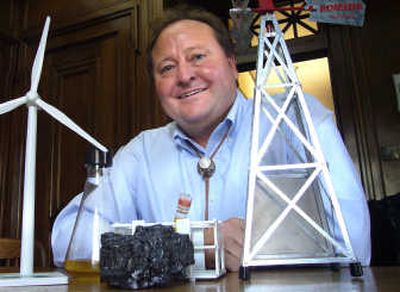

The dog lowered its head and went back to bed. Schweitzer continued discussing his energy independence campaign, which included adjustments to his own life: cutting power use in the governor’s mansion by 25 percent and swapping an SUV for a biodiesel-powered Volkswagen Jetta. Schweitzer’s desk is covered with energy-related doodads: miniature wind turbines, models of hydrogen-powered cars, a vial of biodiesel. There’s also a chunk of black coal, which he would like to see liquefied into fuel oil.

When Schweitzer took office, the famously windy state produced less than one megawatt of wind-generated energy. Today, roughly 140 megawatts of wind power are generated in Montana and 600 megawatts are on the way, Schweitzer said. “I want to continue to develop energy projects. I want transmission lines, I want pipelines, I want coal gasification, I want wind power, I want solar power.”

But critics on both the right and left say Schweitzer has largely failed to transform rhetoric into reality. Environmentalists “are tremendously disappointed” in Schweitzer’s push for coal gasification for its potential to boost emissions of greenhouse gases, said George Ochenski, a prominent liberal political commentator from Helena who publishes a regular column in the Missoula Independent. “The numbers don’t pencil out economically or environmentally for Brian’s pet project,” Ochenski said,

Schweitzer’s lack of political experience has made it tough for him to pull off his ideas and is fueling increasingly “strong-arm tactics,” Ochenski said. “Somehow, the feeling has begun to creep in that this guy is more than a little defined by his initials, B.S.”

But Schweitzer remains popular, with approval ratings consistently in the 60 percent range, according to polls commissioned by Lee Newspapers. Republicans have yet to put forth an opponent for the 2008 election, said Johnson, Lee’s statehouse bureau chief. “They have a hard time going after him,” he said.

Last year, Democrat Jon Tester, an organic wheat farmer from north-central Montana, defeated Sen. Conrad Burns in a pivotal race that helped Democrats win control of the U.S. Senate. Next year, Schweitzer faces re-election, as does the state’s four-term Democrat senator, Max Baucus.

Bob Keenan, considered a top Republican contender for either office, said Schweitzer is vulnerable, despite his populist appeal.

“Schweitzer is definitely a force to be reckoned with,” Keenan said. “If the Republicans want to regain control, they’ve got to take the head of the dragon, and the head of the dragon is Schweitzer.”

The governor acknowledges his ambitious plans will take a lot more work. But he doesn’t think the Republicans have an ounce of a chance of kicking him or his dog out of office.

“I own the middle,” he said.