FDA taking closer look at Lasik surgery

WASHINGTON – Lost in the hoopla of ads promising that Lasik vision surgery lets you toss your glasses is a stark reality: Not everyone’s a good candidate and an unlucky few do suffer life-changing side effects – lost vision, dry eye, night-vision problems.

A decade after Lasik, which stands for laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis, hit the market, unhappy patients will air their grievances before the Food and Drug Administration today as the government begins a major new effort to see if warnings about the risks are strong enough.

How big are those risks? The FDA thinks about 5 percent of patients are dissatisfied, but it can’t provide more specifics. It’s pairing with eye surgeons for a major study expected to enroll hundreds of Lasik patients to try to better understand who has bad outcomes and exactly what their complaints are.

“Clearly there is a group who are not satisfied and do not get the kind of results they expect,” FDA medical device chief Dr. Daniel Schultz said Thursday. The study should “help us predict who those patients might be before they have the procedure.”

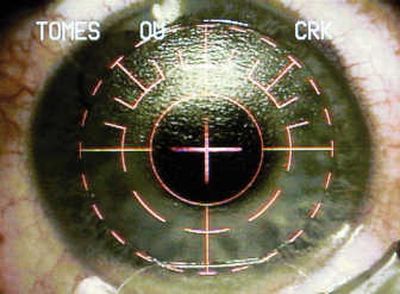

About 7.6 million Americans have undergone some form of laser vision correction, including the $2,000-an-eye Lasik. Lasik is quick and, if no problems occur, painless: Doctors cut a flap in the cornea – the clear covering of the eye – aim a laser underneath it and zap to reshape the cornea for sharper sight.

The vast majority, 95 percent, of patients see more clearly after Lasik – some better than 20/20 – and are happy they had it, said Dr. Kerry Solomon, of the Medical University of South Carolina, who led a review of Lasik’s safety for the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery.

But one in four patients who seeks Lasik is told they’re not a good candidate, he said. And there is little information about just how badly the 5 percent who get it but are dissatisfied actually fare.

Solomon estimates that fewer than 1 percent of patients have severe complications that leave poor vision. Other side effects, however, are harder to pin down. Dry eye, for instance, can range from an annoyance to so severe that people suffer intense pain and need surgery to retain what little moisture their eyes form. That’s the kind of question the FDA’s new study aims to answer.

Dry eye is common even among people who never have eye surgery and increases as people age. Solomon said that 31 percent of Lasik patients have some degree of dry eye before the surgery and that about 5 percent worsen afterward.

But dry-eye specialist Dr. Craig Fowler, of the University of North Carolina, said other research suggests 48 percent of patients experience some degree of dry eye at least temporarily after Lasik. Cutting the corneal flap severs nerves responsible for stimulating tear production, and how well those nerves heal in turn determines how much dry eye lingers long-term, he said.

Even if the risks are low, that’s little consolation to suffering patients.

“As long as you know any ophthalmologist that’s wearing glasses, don’t get it done,” said Steve Aptheker, 59, a Long Island lawyer who was lured by an ad for $999 Lasik surgery and suffered severe side effects that required seven additional surgeries over four years to restore his vision.

The flaps cut in his cornea became wrinkled when they were laid back down, blocking his vision and causing severe pain. A few surgeries later, with a different doctor, Aptheker could function better but couldn’t drive at night and saw a halo around objects that caused serious distortion even during the day. With more operations as new technology hit the market, Aptheker said today his right eye sees as well as it did with glasses before Lasik, but his left remains fuzzy and requires halo-reducing drops.

The FDA has long known of those side effects and for years has had a Web site with warnings for Lasik patients and required that doctors give every potential patient a brochure outlining risks. Today, the agency will ask its outside advisers if its warning efforts go far enough.

But Lasik has been refined in recent years to offer crisper vision with fewer risks, said Dr. Steven Schallhorn, an ophthalmologist who oversaw the Navy’s refractive surgery program until last year when, based in part on his research, the Navy began allowing its aviators to get Lasik.

Schallhorn advises patients to seek what’s called “all-laser Lasik” – in which a thin flap is created using a more precise laser instead of a blade – combined with “wavefront-guided” software that maps subtle irregularities in the cornea before it’s zapped.