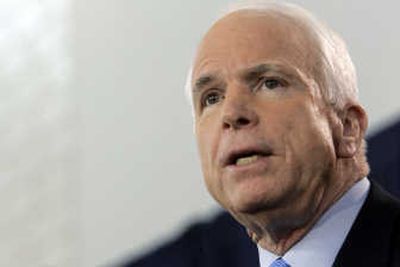

Candidate McCain now backs tax policies he once opposed

WASHINGTON – On May 26, 2001, after then-Sen. Lincoln Chafee of Rhode Island cast his vote against President Bush’s $1.35 trillion tax cut, he trudged back to his office, convinced, he recalled, that he had been the lone Republican to oppose the largest tax cut in two decades.

But Chafee’s staff told him that one other Republican, who had largely avoided the grueling efforts at compromise, had joined him in dissent. That senator, John McCain, was marching to his own beat, Chafee said, impervious to pressure from either side.

Now that he is the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, however, McCain is marching straight down the party line. The economic package he has laid out embraces many of the tax policies he once decried: extending Bush’s tax cuts he voted against, offering investment tax breaks he once believed would have little economic benefit and granting the long-held wishes of tax lobbyists he has often mocked.

McCain’s concerns – about budget deficits, unanticipated defense costs, an Iraq war that would be longer and more costly than advertised – have proved eerily prescient, usually a plus for politicians who are quick to say they were right when others were wrong. Yet McCain appears determined to leave such predictions behind.

“He’s looking forward, not back,” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, McCain’s senior policy adviser.

To supporters, McCain has simply seen the light and now understands the power that business tax relief has to spur economic growth and innovation. Said J.D. Foster, a former Bush White House and Treasury tax policy expert, now at the Heritage Foundation: “It’s logical that he wouldn’t be repeating the arguments he made then. We all learn from experience.”

To critics, it is political pandering. “It’s just part of the new John McCain that’s taking on the conventional wisdom that in tight races, you have to energize the base and win by 50.000001 percent,” Chafee said.

1994 warning

Holtz-Eakin urged skeptics to “wind the clock way back,” saying McCain has supported lower taxes and a smaller federal government throughout his political career.

But McCain’s conflicts with fellow Republicans over taxes date back well before his differences with Bush. In December 1994, after his party swept to control of Congress on tax-cut promises, he challenged Ronald Reagan’s legacy when he warned, “I think we would be making a terrible mistake to go back to the ‘80s, where we cut all of those taxes, and all of a sudden now we’ve got a debt that we’ve got to pay on an annual basis that is bigger than the amount that we spend on defense.”

In 1998, Republican leaders and their tobacco industry allies lambasted McCain’s $516 billion tobacco regulation bill as the “McCain tax,” painting it as big-government overreach and a $1.10 tax increase on every pack of cigarettes.

In 2001, just days before Bush’s first tax cut passed, McCain lamented on ABC’s “This Week” that, “I’d like to see much more of this tax cut shared by working Americans. … I think it still devotes too much of it to the wealthiest Americans.”

Two years later, Bush was back for more: $350 billion in tax cuts, which accelerated the first round and added deep cuts to the tax rates on dividends and capital gains.

“Most of the economists view this as primarily benefiting wealthier Americans,” McCain said on CNBC at the time. “There’s a theory, I think, that’s prevalent – it was true in the 2001 tax cuts – that if you give it to the wealthy people, then they will then, you know, create jobs, et cetera. The interesting thing to me is that most economists will tell you that it’s the middle-income Americans that have been keeping the economy afloat.”

Pushing Bush cuts

Indeed, many of his warnings from those years have come to pass. Numerous expiration dates on those tax cuts, designed to hold down the cost to the Treasury, proved to be just the “gimmicks” he said they were, as Congress extended them repeatedly. The budget deficits he warned about in 2001 re-emerged in dramatic fashion, as did defense spending increases not accounted for when Bush said the tax cuts were affordable. And the war in Iraq proved to be far longer and more expensive than lawmakers had expected when they approved the 2003 cuts, as McCain anticipated.

Yet in Pittsburgh last week, in the face of a projected budget deficit of $400 billion and a sixth year of war, McCain proposed extending Bush’s tax cuts, including the dividends and capital gains tax cuts, lowering the corporate income tax, allowing businesses to write off the cost of new equipment and technology, banning Internet and new cell phone taxes, and permanently extending the business tax credit for research and development.

By McCain’s accounting, his tax proposals would cost the Treasury $200 billion a year.

Conservative tax policy analysts noted that some things McCain predicted in his earlier days did not happen. In 2003, he doubted that a capital gains and dividends tax cut would have any economic effect and said that whatever gains were to be had would be swamped by rising deficits and interest rates. Foster said, however, that the economy took off with the passage of the 2003 tax cut, and although budget deficits have remained, interest rates have stayed low.

Holtz-Eakin said McCain did campaign for president in 2000 on a tax cut plan, albeit one significantly smaller than Bush’s. But it was always meant as a first step toward a simple flat-tax system, Holtz-Eakin said. His latest tax proposal is merely the next step in that process, building on the past eight years of tax changes.

No doubt, conservatives say, McCain is now on the right political side of the tax issue.

“He’s put himself in a position where a conversation about the economy is a conversation about Democratic tax increases and Republican lower taxes, and that’s where any Republican wants to be,” said Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform, who has clashed fiercely with McCain in the past.