New era, pressing problems

Musharraf exit will test fledgling government

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan – The resignation of President Pervez Musharraf will force Pakistan’s untested new civilian government to confront a dizzying array of problems, chief among them an intensifying battle against Islamic insurgents in the nation’s long-lawless tribal areas.

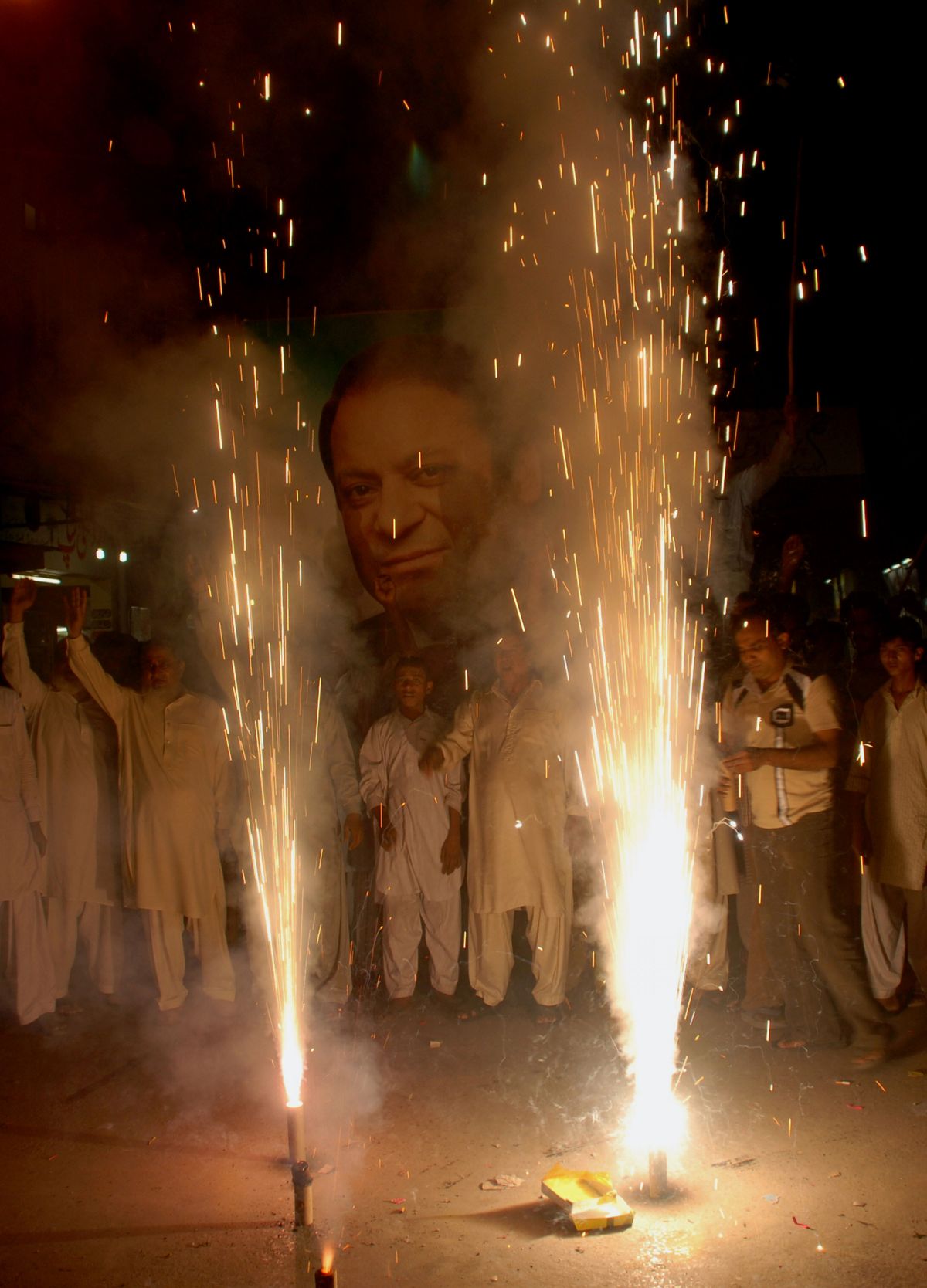

Musharraf’s departure Monday, greeted with near-delirious rejoicing in the streets of Pakistani cities, also opens the door to a potentially debilitating power struggle within the country’s fragile ruling coalition, which was bound together mainly by its anti-Musharraf stance.

Moreover, without the distraction of presidential impeachment proceedings, which were due to begin within days, the 5-month-old government will have to deal with public anger over widespread power shortages and galloping inflation. Many Pakistanis, even those who considered themselves well off a few months ago, are furious that they can barely afford food and gasoline, and that blackouts darken homes and offices many times daily.

“Now this government will have no one but themselves to blame for all that,” said independent political analyst Ejaz Haider.

Nuclear-armed Pakistan, perhaps the most important yet most troubled U.S. ally in the fight against al-Qaida and the Taliban, entered an uncertain new era with the departure of Musharraf, who stepped down only hours before a parliamentary session that was to have been a prelude to impeachment proceedings for alleged constitutional violations. After months of posturing and saber-rattling by both sides, and days of tense back-channel negotiations, the end for Musharraf was astonishingly swift.

Over the course of a few short hours, the 65-year-old president delivered his resignation speech for the cameras, saluted a high-stepping honor guard and climbed into his black limousine, leaving the presidential palace for perhaps the last time.

The competition to succeed him, however, could be bitter and divisive. As stipulated by the constitution, Chairman of the Senate Mohammadmian Soomro took over as acting president. A president is to be selected by lawmakers within 30 days, and the choice may be far from unanimous.

The Pakistan People’s Party, senior partner in the ruling coalition, said there is no doubt the new president will come from its ranks. The party’s ceremonial head, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari – the college-age son of assassinated former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto – flew to the port city of Karachi and declared there would be a PPP president.

“Democracy is the best revenge,” the Oxford student said, smiling as he quoted his mother who was slain late last year.

But a candidacy by his father, Asif Ali Zardari, could prove highly problematic. Many Pakistanis vividly remember Zardari’s corruption-tainted tenure as a Cabinet minister in the 1990s, when he was known as “Mr. 10 Percent” for the kickbacks he allegedly demanded.

The PPP has suggested the new president might be a woman, which could pave the way for the well-respected new speaker of Parliament, Fehmida Mirza.

Another possible candidate is the new prime minister, Yousaf Raza Gilani, who earned his political stripes in Musharraf’s jails.

However, the head of the junior party in the ruling coalition, former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, could also assert a claim on the presidency. Without his insistent demands that Musharraf be ousted, the PPP would probably have been content to allow the president to serve out a figurehead tenure.

Another looming question is just how much power the new chief executive will have.

Musharraf’s authority had waned dramatically in recent months, first with his relinquishing the post of army chief of staff in November and again with his party’s crushing defeat in parliamentary elections six months to the day before he resigned.

During his nearly nine years in office, however, he had worked assiduously to strengthen the powers of the presidency. The ruling coalition had been preparing a package of reforms aimed at reversing some of those changes, but the Pakistan People’s Party may now resist enacting those limitations on presidential authority.

In his speech, Musharraf declared that he had asked for no concessions in exchange for his resignation, although intense indirect negotiations had been under way for days aimed at securing a promise of legal immunity.

If Musharraf remains in the country rather than heading into exile, Sharif might seek to bring treason charges against him, something he has repeatedly pledged to do. The president’s continued presence in Pakistan would also pose a major headache for security forces, which would be charged with his protection. Musharraf has been the target of repeated and elaborate assassination attempts by al-Qaida and other Islamic militant groups.

The Bush administration had hoped that Musharraf, even with significantly diminished powers, could have served as a transition figure while the new civilian government found its footing, particularly in its dealings not only with Pakistan’s military, but with the nation’s powerful and shadowy security and intelligence apparatus.

Pakistan’s military made a point of staying out of the impeachment crisis. But the civilian government recently had a bruising run-in with the intelligence services when it clumsily tried to bring the premier spy agency, the Directorate of Inter-Services Intelligence, under the purview of the civilian Interior Ministry. That order, issued as Gilani was en route to a meeting with President Bush in July, was embarrassingly rescinded after an outcry within the intelligence community.

At the height of his friendship with the United States, which probably peaked two years ago, Musharraf was feted in the White House and hailed as a warrior-statesman. His autobiography, “In the Line of Fire,” was a best-seller in the United States.

And on Monday, the Bush administration had kind words for the departing president.

Musharraf, said Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, “has been a friend to the United States and one of the world’s most committed partners in the war against terrorism and extremism.”

“President Bush appreciates President Musharraf’s efforts in the democratic transition of Pakistan, as well as his commitment to fighting al-Qaida and extremist groups,” echoed White House spokesman Gordon Johndroe.

But lately, Musharraf’s American patrons had made clear their growing disenchantment as billions of dollars in military aid yielded little visible result in the fight against al-Qaida and the Taliban. Osama bin Laden, still believed to be at large nearly seven years after the Sept. 11 attacks, stood as a frustrating symbol of the inability of Pakistani forces to penetrate militants’ tribal sanctuaries. U.S. ground forces have not been allowed to operate in Pakistan out of respect for the nation’s sovereignty.

The impeachment crisis this month has overshadowed the Pakistani military’s strongest move against militants in the tribal areas since the 2001 U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan. The new civilian government initially disconcerted Western allies by seeking to negotiate with militants in the tribal areas. But for days now, Pakistani helicopter gunships have been strafing suspected militant hide-outs in the Bajur tribal agency, thought to be a sanctuary of major al-Qaida figures. By Pakistani estimates, up to a quarter-million civilians have fled the Bajur fighting, the largest internal displacement in the country’s history.

Although many of Musharraf’s foes hoped for more sweeping retribution than his departure seemed to afford, some of his enemies urged a focus on reversing his actions, including his firing of dozens of senior judges during 2007’s bout of emergency rule.

Aitzaz Ahsan, the lawyer who led the grass-roots uprising that heralded Musharraf’s eventual downfall, said it was time for members of the judiciary, the shock troops in that movement, to “lower the black flags and rejoice.”

Ahsan, who was jailed and then kept under house arrest for weeks under the emergency rule, said he hoped for accountability, but not vengeance.

“I am not a witch-hunter,” he said.