Modern Spokane forged in struggle

Bank failures, layoffs and swan-diving stock portfolios are nothing new in the Inland Northwest. It has all happened before – bigger, deeper and longer (or so we can hope) – during the only Depression that has earned the adjective “Great.” Here’s how the Great Depression played out in the Spokane area:

Nobody needed Twitter and instant-messaging to spread the news throughout Spokane on Oct. 24, 1929: Something big and ugly was happening in the stock market.

Breakfasts went half-finished. Agitated investors hopped on streetcars and converged on Spokane’s “wire rooms,” where stock quotations were posted on boards in the brokerage houses. By midmorning, no more bodies could squeeze in.

The crowds watched in horrified fascination as the numbers showed what a reporter called “a tidal wave of price-wrecking.”

They had no way of knowing it was the beginning of the 1929 stock market crash, the first day of the Great Depression and the day they would later know as Black Thursday. They knew only that it was an exceedingly lousy Thursday.

“Spokane ‘Lambs’ Shorn By Slump,” screamed The Spokesman-Review’s headline.

The reporter tried to put the best face on it by pointing out that Spokane was calm in comparison with New York, where some traders collapsed and had to be carted off the floor. The overall mood of the Spokane throng, he said, was “sober.”

Sober was inadequate to describe the mood several days later on Black Monday and Black Tuesday (Oct. 28 and 29), when the market dropped even more catastrophically. Once again, the crowds converged on Spokane’s wire rooms. By this time, investors were in the full grip of panic, and the brokerage employees could only hold on for dear life.

“W.V. Stenton, his eyes showing a sad need of sleep, has been on the floor of the Doherty office from early morning until past midnight, meeting anxious stockholders,” The Spokesman-Review reported on Oct. 30, 1929.

This is how the Great Depression officially began in Spokane, but in truth, times had been tough for years in the Inland Northwest. Mining and logging were already in decline. Farmers in the West had been especially beleaguered.

“In the new farmlands of the West, hard times had hit well before 1929,” according to Spokane-raised author Timothy Egan in his book “Breaking Blue,” which took place in Spokane during the Great Depression. The agricultural depression, he wrote, had started nine years earlier.

In fact, five banks in Spokane County had already failed earlier in 1929.

The full impact of this new disaster on the Inland Northwest was summed up in two more headlines the day after the Crash: “Panic Splashes Into Wheat Pit” and “Mining Stocks Slip … Some Margins Wiped Out.”

Yet as in the rest of the United States, the Great Depression took several more years to build up to its dismal peak in Spokane. Most people tried to live as usual, although they pinched their pennies, planted gardens and hunkered down. Gilbert and Dorothy Nokes, a young married couple, built chicken coops in back of their Whitworth-area home.

“We took a case of eggs to town every week,” Dorothy Nokes said in a 2004 interview. “That’s where you made your money to get your groceries.”

Robert “Mac” MacDonald of Spokane later remembered making what he called “the first tube socks.”

“When your socks were worn, you’d sew the top up, cut the toe off and wear them backwards,” he said.

By 1931, the troubles from Wall Street had reached into the Inland Northwest. Building permits nosedived; new construction was almost nonexistent. Farmland lay fallow due to foreclosure. Businesses went bankrupt and jobs disappeared. One cash-poor Kettle Falls lumber mill paid its crew in scrip, which was slightly better than not paying them at all.

In a particularly demoralizing development for Spokane’s youngsters, the Manito Park Zoo was closed in 1932 because of plummeting tax revenues. Three bears were shot and stuffed.

Two banks went under in Spokane in 1931, followed by a sickening spate of bank failures in 1932, including three affiliated banks on the same day, April 15, 1932: American State, Spokane State and Wall Street State.

One of the bank’s directors stood on the balcony and announced to a frantic crowd that everyone would get all of their money, which he soon was forced to amend to $200 of their money, then $100, then $50, according to an account in Carolyn Hage Nunemaker’s “Downtown Spokane Images: 1930-1949.”

Leading Spokane businessmen tried to ease anxieties, pointing out that these were small banks. Yet, you can almost hear the panic in their exhortations not to panic.

“We are shocked at any bank closure, but looking at the problem in the face, we can feel assured as to Spokane’s financial future,” said Lloyd Hill, president of the Spokane Rotary Club. “I have gone over the matter carefully and urge our people not to let any hysteria or false rumors disturb them, but to go about their business as usual.”

The next month, four more small banks failed.

However, Spokane did indeed escape most of the banking panic that swept the nation in 1932 and 1933. Washington’s Governor Clarence D. Martin declared a “bank holiday” (bank closure) from March 3 to March 6, 1933, as a way to protect banks from being overrun by panic withdrawals, yet some of the big banks in Spokane announced that they didn’t need it. Washington Trust, for one, opened for business as usual on March 3, 1933, and weathered a brief run which “had spent itself” by early morning. By 11:30 a.m. only four people were in the lobby, one of whom was “a boy industriously patronizing the water fountain,” said The Spokesman-Review.

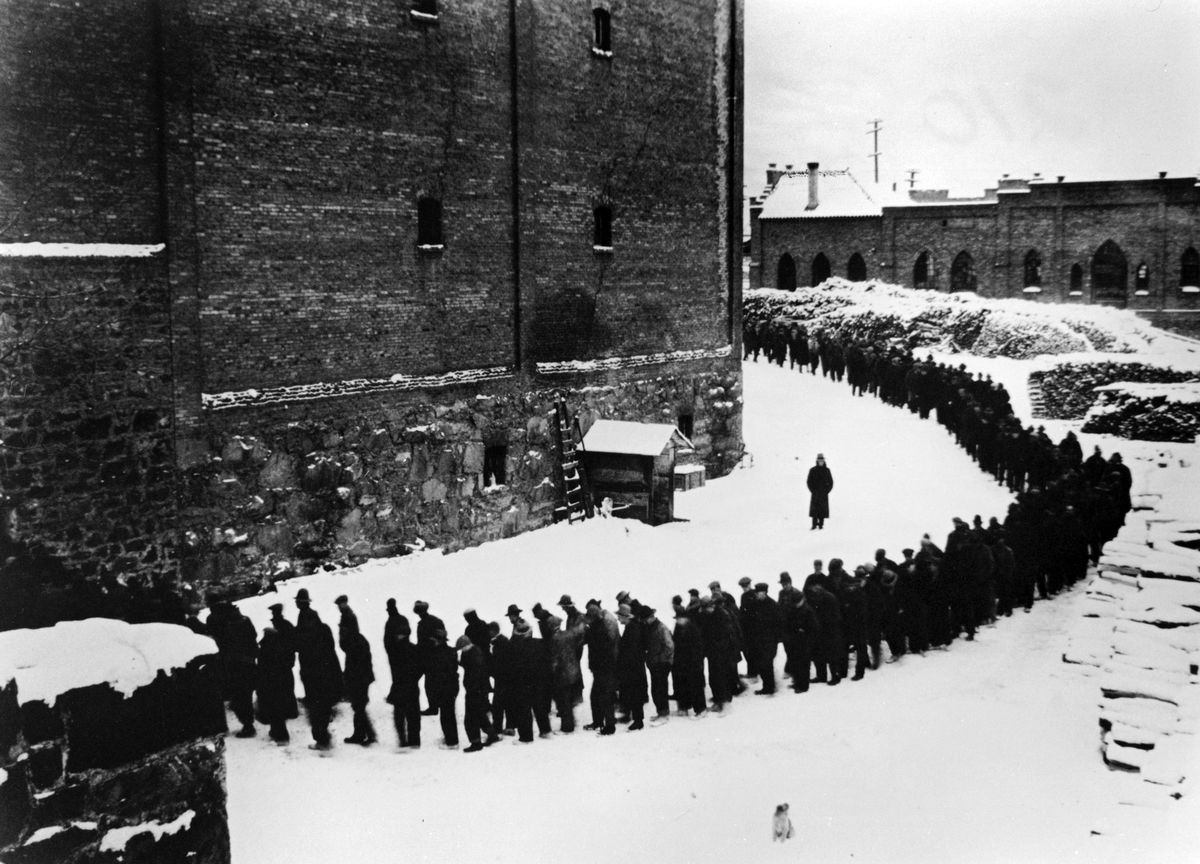

Keeping money was one thing; making it was an entirely different problem. Spokane’s unemployment peaked in the 1930s at about 25 percent, close to the national average. Spokane’s employment problems were exacerbated by a particularly cruel fact: Hundreds of unemployed men (and their families) were arriving in Spokane every day by box car because of a false perception that jobs were available in the Northwest. They alighted in Spokane because it was such a huge railroad “division point.” They lived in hobo “jungles” by the Spokane River and in “shack-towns” beneath the downtown bridges on both sides of the river.

“The ever-increasing army that throngs to the freights is one of the most pathetic aspects of the depression,” wrote Margaret Bean of The Spokesman-Review, who walked through the vast Northern Pacific rail yards at Parkwater (near Felts Field) in October 1932.

There, she saw men who “once drew large salaries,” hundreds of boys and girls “traveling in bands,” and entire families riding the freight cars “in a useless hope of finding green pastures.”

“The other morning, when a through freight slowed down as it entered Parkwater, more than 300 men, women and children dropped from the train before it entered the Northern Pacific yards,” wrote Bean. “They headed for the jungles. Some of the passengers didn’t light until the train stopped. The door of one ‘empty’ swung open on its grating hinges and out climbed a fairly young woman. She carefully placed her newspaper bundles on the ground and then reached into the car to take off her small child and a parrot in a cage.”

When Bean approached some members of this vast “army” to ask where they were going, she received this answer not once, but many times: “Chasing the rainbow.”

The nearby Schade Brewery, shut down due to Prohibition, became a roosting point and soup kitchen for transients. They named it, sardonically, the Hotel De Gink, “gink” being slang for an odd fellow.

This was the nadir of the Great Depression, yet even in these toughest of times, most people pulled together and helped out their neighbors. In 1932, Alexander Barclay, a Coeur d’Alene doctor, forgave all debts owed to him as a way to help people “retain their courage.” Dorothy Nokes remembered the Great Depression as tough economically but “friendlier” than modern Spokane, because of the overwhelming sense that everybody was in the same boat.

People craved merriment more than ever. The Fox Theater, a “million-dollar” movie and concert palace, opened on Sept. 3, 1931 and proceeded to provide plenty of non-depressing entertainment, ranging from comic Ben Doba (“The Convivial Inebriate”) to violinist Jascha Heifetz to Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon.”

Eddie Cantor and Al Jolson played Spokane’s music halls. Boxing hero Jack Dempsey barnstormed through Spokane. In 1933, Prohibition was repealed, making it a little easier for the Inland Northwest to either laugh away its problems or drown them.

Meanwhile, the mining, lumber and wheat industries continued to wallow. Spokane County’s population dropped from 154,450 in 1933 to 150,020 in 1934.

Yet recovery began slowly to take hold, partly due to developments in that other Washington. In March 1933, new President Franklin D. Roosevelt started the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a work relief program in which young, unemployed men were sent out to work in the nation’s forests and parks.

This program was particularly significant in the Inland Northwest. By August 1933, a whopping 45 CCC camps, employing 10,000 men, were already operating within 100 or so miles of Spokane. Many more would open later.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA), a relief agency established in 1935, also put thousands of unemployed people to work on what would later be called infrastructure. The WPA was responsible for, among other things, High Drive, Rutter Parkway, parts of Geiger Field and mile after mile of sewers and water mains. The WPA even established the Spokane Arts Center, which put artists and art teachers to work.

Another federal agency, the Public Works Administration, was responsible for the project that deserves the most credit for lifting the Inland Northwest out of its ravine: the Grand Coulee Dam.

Work began on the site in 1933; heavy construction began in earnest in 1935. By the time it was finished in 1941, the project had employed 12,000 workers. They were paid, on average, the then-excellent wage of 85 cents an hour.

With employment picking up, so did business. By 1939, downtown Spokane business activity was back to 1929 levels.

Then, in 1941, World War II arrived and overwhelmed any lingering traces of Depression in the Inland Northwest. Industry was poised to revive; Spokane County’s population was poised to explode.

The Great Depression would fade into history, although its legacy survives in the roads of Riverside State Park, the Vista House at Mount Spokane and the sewer systems beneath our feet – all built by the CCC and the WPA.