Super Bowl has a nice ring to it

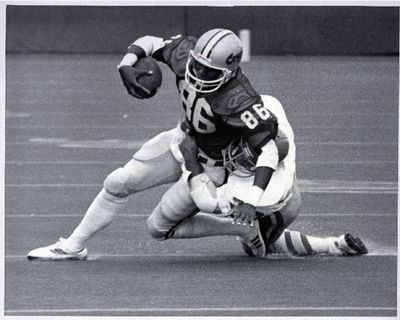

Mike Wilson was never The Star by today’s me-first standards.

Not at Washington State, where the Cougars lost more games than they won and he caught twice as many passes as a sophomore than he did the next two seasons combined.

And not during an unlikely 10-year career in the National Football League, first overshadowed by San Francisco teammates Dwight Clark and Freddie Solomon, then by Jerry Rice and John Taylor.

But take the names Joe Montana, Ronnie Lott, Eric Wright and Keena Turner, or Lynn Swann and John Stallworth, and add Mike Wilson.

That becomes the list of the 49ers who played on all of San Francisco’s Super Bowl champions in the 1980s and the list of wide receivers, Wilson and two Pittsburgh Steelers, who have four Super Bowl rings.

“My statistics could have been better, but it was about winning,” Wilson said. “Sometimes I think that’s missing today. I can’t complain. History puts it in perspective.”

Wilson ending up in such rare company would have to be considered unusual by any measure.

Although Wilson was a highly regarded football and basketball player coming out of Carson (Calif.) High School, many big-time football schools saw the 6-foot-4, 210-pounder growing into a tight end. Not the Cougars, and with Jack Thompson slinging the ball all over the field, Wilson jumped at the chance to go to a pass-first program.

Freshmen didn’t play in those days, but when his time came, Wilson made quite a splash. Playing against UNLV at Albi Stadium in the 1978 season opener, he caught five passes for 106 yards and a touchdown. He finished the season with 31 receptions for 481 yards and three scores.

Unfortunately, because of injuries, he never came close to matching that success for the rest of his career, when Steve Grant and then Samoa Samoa were the quarterbacks. But with that enticing size and 4.4 speed, the Dallas Cowboys drafted him in the ninth round of the 1981 draft.

Then came the highlight of his professional career, according to Wilson, Super Bowls included.

“The best thing, I think, was getting released by Dallas and signing with the 49ers the next day,” he said. “It was really just a matter of having the aptitude for understanding Bill Walsh’s system.”

His rookie season, playing on an unheralded team of stars-to-be, ended with a 26-21 win over Cincinnati in Super Bowl XVI, known in 49ers lore as the game following The Catch.

Wilson went on to play in 136 regular-season games, starting 28, catching 159 passes for 2,199 yards with 15 touchdowns. He also appeared in 18 playoff games.

“I think I matured and blossomed when I got in the NFL as opposed to my three years starting at Washington State,” he said. “I was very consistent. In hindsight, not to be arrogant, I think I could have started for a lot of teams. I accepted my role. My talent level was up there but obviously we had some exceptional stars. That was the key to the 49ers, we checked our egos at the door.”

Wilson retired after the 1990 season with an idea of working in a front office, but Walsh, who had returned to Stanford, called again.

“Coaching wasn’t a great aspiration,” Wilson said. “Bill Walsh called me … offered me a job. … I’ve been coaching since. It’s been very rewarding.”

Wilson coached wide receivers at Stanford, the Oakland Raiders, Southern California and the Arizona Cardinals, until a coaching change cost him his job before this season.

He’s proud of his work. During his time at Stanford, converted quarterback Justin Armour earned All-Pac-10 honors opposite Keyshawn Johnson; three USC wide receivers were drafted, including first-rounder J.R. Soward; his most renowned Raider was Tim Brown; and Anquan Boldin and Larry Fitzgerald both caught more than 100 passes for more than 1,000 yards in 2006 for the Cardinals.

“For me coaching is not about my name being recognized, it’s about my players … being productive,” Wilson said.

After a year off he’s trolling for work now.

Without a coaching job Wilson has spent most of his time in Manhattan Beach, Calif., where his wife, Tona’ Broussard-Wilson, has her own freelance production company.

Their oldest daughter, Samantha, is a freshman at Yale, the youngest, Emma, is a senior weighing options that include Stanford and the Ivy League.

“I’m very proud of them,” Wilson said. “It wasn’t me, it was just them being motivated to excel in classroom. I admire that and I encourage that.”

Both girls played some basketball but preferred track and field.

“Samantha was as competitive in the classroom as I was on the football field,” Wilson said. “You can’t knock that. She didn’t care how many points she had in basketball but she wanted all A’s. More power to her. Emma is the same in the classroom.”

The buildup to the Super Bowl is a special time for Wilson and his former teammates as they reflect on their accomplishments.

“Obviously, whenever you talk about my career and the five guys on four Super Bowl teams, it wouldn’t have happened without the great Bill Walsh giving us the opportunity. … It was a phenomenal run,” he said. “With the Super Bowl around the corner you can’t help but reminisce.

“I think the first one, Jan. 2, 1982, was the best. There were no expectations for the 49ers to have success; we had so many young players, rookies, including myself. To rise to the pinnacle was unexpected. After we established that level of excellence it almost became expected.

“During the ‘80s we were very consistent. In my opinion, with creation of free agency, you won’t see that. New England is doing a good job. New England is as good as any team I’ve seen on both sides of the ball. But the game has to be played. That’s the reality. No one expected the 49ers to beat Dallas in the 1981 championship game. Anything can happen. That’s the beauty of it.”