Ethanol dominates U.N. food conference

ROME – A global summit over how to feed the hungry and pump up food stocks – tasks that could demand more than $20 billion a year in aid – magnified a debate over diverting grains to produce biofuels in the world’s most developed countries.

As hundreds of representatives gathered at a United Nations conference Tuesday to address the global food crisis, leading strategists took issue with the increasing interest in and use of ethanol, a cornerstone of an evolving U.S. policy on alternative fuel sources.

A clear split also emerged between the largest ethanol producers, Brazil and the United States, as Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva defended ethanol use but then drew blunt distinctions between corn and Brazil’s sugar-cane based products. He took aim at how the U.S. subsidizes its Midwestern corn farmers and laid out cost differences for production of each country’s brand of ethanol.

“There is good ethanol and bad ethanol,” da Silva said. “Good ethanol helps clean up the planet and is competitive. Bad ethanol comes with the fat of subsidies.”

The fuel dialogue played out over a day of somber revelations of food demands during the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization’s high-level conference on world food security. U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, in an opening address, pointed to soaring populations and shrinking resources as a test of survival.

Poorer countries with substandard farm methods will be hardest hit, but rich nations struggling with increasing fuel costs will also feel the hurt, Ban said. By 2015, the world’s population, now 6 billion, will rise to 7.2 billion, he said. By 2050, 9 billion people are expected to inhabit the Earth.

“The world needs to produce more food,” Ban said. “Food production needs to rise by 50 percent by the year 2030 to meet the rising demand.”

Ban estimated the global cost of solving the food crisis could exceed $20 billion a year over a number of years.

The conference is focused on forging strategies, policies and practical programs to build food sustainability. FAO head Jacques Diouf, in his remarks, took wealthy nations to task for ignoring previous calls to action that he said could have prevented rice and wheat shortages and ensuing civil unrest in Haiti, Somalia and other poor nations.

Diouf’s comments set the stage for discussions that will continue for the next two days over how to encourage and support food production and possible reforms within FAO over how to purchase and distribute food.

But all discussions of the food crisis were constantly twinned with talk of the spiraling cost of fuel and its impact on the food supply.

The U.S., the nation that gives the most food aid in the world, found itself chided for pursuing an alternative fuel policy that some blamed for current grain shortages. In 2007, almost one-quarter of U.S. corn crops went to ethanol; this year, the share is expected to reach one-third, although the figures are a matter of contention. Meanwhile, over the past two years the price of a bushel of corn has more than doubled.

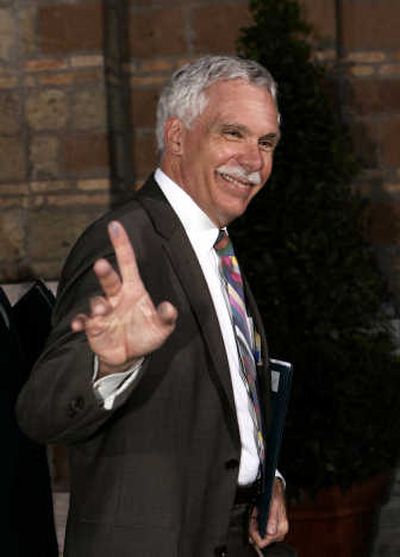

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Ed Schafer reacted mildly Tuesday to the criticism heard at the conference, some of which first arose in a UN report released last week.

“I’m not here to take offense,” he said about the ethanol exchanges. “It seems to me that what we need to do is focus on the real issues. … Focusing on biofuels will not solve the food crisis.”

Schafer said biofuels account for only about 3 percent of the rise in food prices. Others put that figure higher; Oxfam International says that biofuels may contribute 30 percent to the added costs.