For ‘Billy,’ the show must go on in Spokane

The squabble over Kitty Oakes’ estate has breathed fresh life into one of the more “incredible-yet-true” scoops of my columnist career.

Namely the saga of Billy Tipton, the Spokane jazz musician who spent 54 years posing as a man.

Reporter Karen Dorn Steele laid out many of the details today in her fascinating story:

That Tipton and Oakes lived a “Leave it to Beaver” life as man and wife in a tidy South Hill home on leafy Manito Boulevard; that their adoption of three boys wasn’t legal; that Tipton’s sexual identity was revealed to the total shock of the sons, friends and others after the entertainer’s death in 1989.

That yours truly broke the news thanks to a tip from then-Spokane County Coroner Graham McConnell.

Twists. Turns. Secrets.

The Tipton transgender tale was so over-the-top that it always seemed better suited for an opera than a newspaper.

And it’s about time Spokane got a chance to see that opera.

That’s my pitch for today.

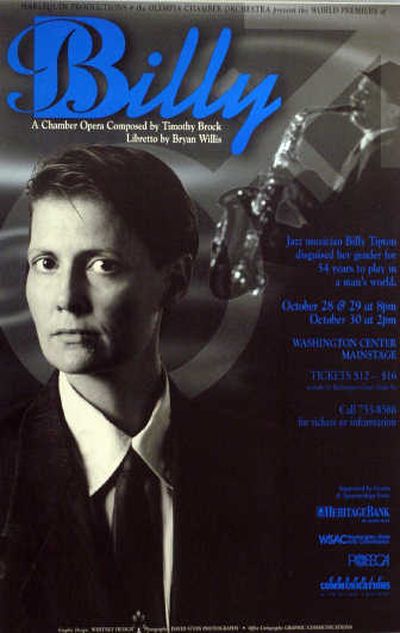

Largely lost with the years is “Billy,” a brilliant original opera about Tipton performed just three times in 1994.

It always bothered me that those three performances took place in Olympia and not where Tipton lived, performed and died.

Now that the Fox Theater is the beautifully refurbished home of the Spokane Symphony, I ask you …

Wouldn’t the community’s art deco palace be a fine and fitting venue for the likes of “Billy”?

The only obstacle is, oh, maybe 40 or 50 grand. But, hey, all we need is an art patron with a magnanimous spirit and checkbook to match.

Bryan Willis, who wrote the libretto for “Billy,” said it took $25,000 to produce the opera, which was a joint venture of the Olympia Chamber Orchestra and Harlequin Productions.

That was an act of artistic courage, to be sure.

There are a lot of ways to make money. Staging an opera usually isn’t considered one of them.

Yet the compelling and contemporary real-life story of “Billy” drew people who would never buy a ticket to an opera.

Because of that the production finished in the black, Willis said.

Maybe 400 bucks in the black. But in the black is in the black.

Here in Spokane, this operatic tribute to one of our most complex and intriguing former citizens would be a huge draw.

Willis, an Olympia resident, is now a notable playwright who has led workshops and leads the Northwest Playwrights Alliance.

In 1994, Timothy Brock, who wrote the opera’s haunting and rich score, was director of the Olympia Chamber Orchestra.

He is now an internationally celebrated composer and conductor. Brock, according to his biography, “has written new or restored original orchestral scores to 26 silent films,” including Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 score to “Modern Times.”

OK. I suppose I should mention my own selfish interest in seeking a “Billy” comeback.

The tenor is Doug Clark.

Yeah. I hear you. I still don’t believe it, either.

Nobody, in fact, was more surprised than I was upon learning that Willis had written me into his opera.

I was there with my family on opening night. We watched in slack-jawed amazement as the Doug Clark character appears in the first act.

Sitting before a glowing word processor, the actor began to sing the very words I wrote when telling the world about Tipton.

“For more than half a century, jazz musician Billy Tipton kept guard over a fantastic seee-cret…”

I thought my daughter, Emily, was going explode from suppressed giggles.

Even more shocking was seeing Troy Fisher, the guy who played me.

Slim. Handsome. Thick mane of blond hair.

Of all the weird damn things to come out of the Billy Tipton story, that last one might be the topper.

But the production was first rate, the music gorgeous.

Willis and Brock put a sympathetic, human face on Dorothy Lucille Tipton who, in 1933, borrowed her younger brother’s name and left Kansas City to pursue a music career.

The opera focuses on Tipton’s emotional last moments. Dying from a bleeding ulcer, the musician wrestles with the issue of whether to reveal the secret.

Tipton debates his alter egos and ignores a former wife who urges him to seek medical help.

Willis told me last week he’d be thrilled to see “Billy” performed again. I wasn’t able to reach Brock, but Willis is confident his friend will share his view.

I’ll never forget breaking the story of Tipton. Or the fact that the very people who thought they knew Tipton best in fact knew nothing at all.

After receiving the coroner’s tip, I began calling musicians who had played with Tipton night after night. I wanted to see what they thought of their departed friend.

How well did Billy Tipton keep the secret?

The words of Don Eagle, a wonderful guy and fine guitarist who died in 1996, told me everything I needed to know.

“Doug,” exclaimed Eagle, “Billy Tipton was a man among men!”