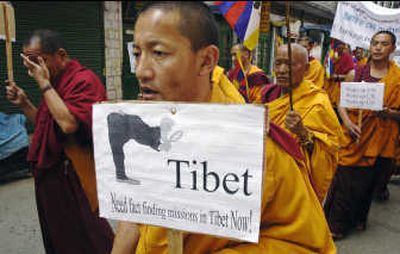

Monks shedding roles as pacifists

BANGKOK, Thailand – Buddhist monks hurling rocks at Chinese in Tibet, or peacefully massing against Myanmar’s military, can strike jarring notes.

These scenes run counter to Buddhism’s philosophy of shunning politics and embracing even bitter enemies – something the faith has adhered to, with some tumultuous exceptions, through its 2,500-year history.

But political activism and occasional eruptions of violence have become increasingly common in Asia’s Buddhist societies as they variously struggle against foreign domination, oppressive regimes, social injustice and environmental destruction.

More monks and nuns are moving out of their monasteries and into slums and rice paddies – and sometimes into streets filled with tear gas and gunfire.

“In modern times, preaching is not enough. Monks must act to improve society, to remove evil,” says Samdhong Rinpoche, prime minister of the Tibetan government-in-exile and a high-ranking lama.

“There is the responsibility of every individual, monks and lay people, to act for the betterment of society,” he said in Dharamsala, India, discussing protests in Tibet this month that were initiated by monks.

In widespread protests over the past three weeks, crimson-robed monks – some charging helmeted troops and throwing rocks – have joined with ordinary citizens who unfurled Tibetan flags and demanded independence from China. Beijing’s official death toll from the rioting in Lhasa is 22, but the exiled government of the Dalai Lama says 140 Tibetans were killed there and in Tibetan communities in western China.

Bloodshed also stained last fall’s pro-democracy uprising in Myanmar, dubbed the “Saffron Revolution” after the color of the robes of monks who led nonviolent protests against the country’s oppressive military regime.

In Thailand, followers of a Buddhist sect took part in street demonstrations which led to the ouster of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra two years ago.

Indeed, the activism reflects another side of Buddhist history. Despite the faith’s image of passivity, an aggressive strain has long existed, especially in the Mahayana school of Buddhism, practiced in Japan, Korea, China and Tibet.

Before China’s takeover of Tibet in 1959, warrior monks sometimes wielded more power – and weaponry – than the army. Lhasa’s Sera monastery, a hotbed of the recent protests, was particularly noted for its elite fighters, the “Dob-Dobs,” who in 1947 took part in a rebellion that took 300 lives.

“Use peaceful means where they are appropriate, but where they are not appropriate, do not hesitate to resort to more forceful means,” said the previous, now deceased Dalai Lama when Tibet fought the Chinese in the 1930s.

Christopher Queen, an expert on Buddhism at Harvard University, says the new trend among some of the world’s 350 million faithful is expanding from individual spiritual liberation to attacking problems such as poverty and environmental blight that affect whole communities or nations.

Sri Lanka’s Sarvodaya Shramadana, or “Mundane Awakening,” provides everything from safe drinking water to basic housing in more than 11,000 poor villages. And in India, Buddhist groups are fighting for the rights of “the untouchables,” the lowest caste.

Global and loosely affiliated, originating at the grass roots rather than atop religious hierarchies and more muscular than meditative, this movement is widely known as Engaged Buddhism.

“Engaged Buddhists are looking at the social, economic, and political causes of human misery in the world and organizing to address them. The role of social service and activism is clearly growing in all parts of the Buddhist world,” Queen said.

While not immune to spilling blood, Queen says “the Buddhist tradition is rightly known for the systematic practice of nonviolence.”

Indeed, the Dalai Lama has decried the recent violence while supporting people’s rights to peaceful protest. And Samdhong, the prime minister-in-exile, adds: “If (monks) want to fight, they have to disrobe and join the fighters.”