Evangelical elite explored

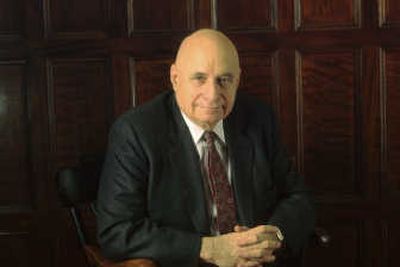

For decades, Boston University sociologist Peter Berger says, American intellectuals have looked down on evangelicals.

Educated people have the notion that evangelicals are “barefoot people of Tobacco Road who, I don’t know, sleep with their sisters or something,” Berger says.

He thinks it’s time for that attitude to change.

“That was probably never correct, but it’s totally false now and I think the image should be corrected,” says Berger.

His university’s Institute on Culture, Religion and World Affairs is leading a two-year project that explores an “evangelical intelligentsia” which Berger says is growing and needs to be better understood, given the large numbers of evangelicals and their influence.

“It’s not good if a prejudiced view of this community prevails in the elite circles of society,” says Berger, a self-described liberal Lutheran. “It’s bad for democracy, and it’s wrong.”

The study is being directed by Berger and Timothy Shah, an evangelical political scientist at the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life.

Shah is documenting the history of the evangelical movement, including its historical hostility to higher learning, a subsequent revival of scholarship, and the minds and ideas it has since produced.

Some experts aren’t convinced evangelical scholars have made as much progress as they think.

Boston College sociologist Alan Wolfe, who wrote an article in The Atlantic, “The Opening of the Evangelical Mind,” in 2000, says despite the success of some evangelical scholars, many have retained an insularity and defensiveness that limits their effectiveness.

“There isn’t enough mixing in the larger world of ideas,” he says.

An estimated 75 million Americans are evangelicals, people who emphasize a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and commit to spreading the message of salvation though his redemptive death.

Evangelicals say they often aren’t well-understood beyond their Bible-banging, evolution-hating caricature.

Many people equate evangelicals with fundamentalists, an evangelical subset that interprets the Bible literally – as in the six calendar days of creation – and is home to ardent evolution opponents. But Shah says most evangelical scientists believe in evolution guided by God.

A quote from a 1993 Washington Post article, describing followers of two leading evangelists as “poor, uneducated and easily led,” remains infamous among evangelicals as an example of the bias they claim to face.

After President Bush won the 2004 election, New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd wrote Bush had won the evangelical vote, in part, by appealing to their “fear of scientific progress.”

Mark Noll, an evangelical and well-known historian at the University of Notre Dame, says the stereotype is perpetuated because both religious and secular thinkers have created an either-or choice between science and God.

“It’s just false,” Noll says. “You go back to (Isaac) Newton and (Johannes) Kepler, the founders of early modern science were theists of one sort or another.”

Shah says a major split between evangelicals and popular culture came after the so-called Scopes monkey trial in 1925, in which a teacher was convicted of violating Tennessee’s ban on teaching evolution – a decision later overturned.

Defense attorney Clarence Darrow told his opponent, William Jennings Bryan: “You insult every man of science and learning in the world because he does not believe in your fool religion.”

Two years later, Sinclair Lewis’s “Elmer Gantry” poked at the anti-intellectualism of leading evangelicals and cast them as corrupt frauds. At the same time, Shah says, the country’s institutions of higher education were taken over by people hostile to Christian faith.

“(Evangelicals) felt totally besieged,” he says. “They felt like the culture made fun of them.”

Evangelicals began to emerge from “their self-imposed ghetto” in the 1950s and ‘60s after prodding from leaders such as Billy Graham, who urged a new intellectual boldness, Shah says.

They also became more prosperous and better educated, and produced more scholars as a result, says Berger.

Notre Dame is home to several of the best-known evangelical thinkers besides Noll, including philosopher Alvin Plantinga, whose “free will defense” takes on the logical problem of evil, and historian George Marsden, who won the prestigious Bancroft Prize for his book on colonial preacher Jonathan Edwards.

Other notables who identify themselves as evangelicals include federal judge Michael McConnell, a top constitutional law scholar; Francis Collins, director of the Human Genome Project; and Duke professor Peter Feaver, a former top director at the National Security Council.

As evangelical scholars seek greater influence, Boston College’s Wolfe warns that getting respect is a two-way street.

He points to things like “faith statements” at evangelical colleges, which require professors to proclaim Christian belief. A prospering intellectual culture wouldn’t make that requirement and shut other views out, Wolfe says.

“It’s when you view your tradition with such confidence that you want to offer it to others … that’s when you’ve made it,” he says. “I don’t see evangelicals having that pride in their own tradition, yet.”