Businesses hope programs pay off for small towns

NEW ULM, Minn. – At the Country Loft gift shop, customers buying homemade fudge or a porcelain doll will come away with something more: cash back on a card to use for more shopping and a good feeling about supporting a charity and their local economy.

The store is part of SmartTown Alliance, a network of small businesses aimed at helping communities keep shoppers close to home rather than traveling to bigger nearby cities. Since it was begun three years ago, it has expanded to three Minnesota towns and is in the works in about a dozen other places.

“I looked at it as maybe it’s a shot in the arm for a small community,” said Country Loft owner Nancy Kokesch. “Small-town America is slowly dying.”

Some retailers in the program are reporting higher customer traffic, while others say it needs more of a push. For it to succeed, consumers have to start shopping with their hearts and not only their wallets – something experts said isn’t automatic.

A swipe of the card at the register sends a portion of the sale price to a charity the customer has chosen. Shoppers also get a bit of money put back on their cards for future purchases within the network. Unlike some other loyalty credit or debit cards, the SmartTown card can be used even if a customer pays by cash or check.

Programs like Target Corp.’s REDcard – which lets shoppers give up to 1 percent of their store spending to their local schools – shows that loyalty cards can work, said Michael Bouchey, chief executive of Alliance Card Inc., which runs the program in New Ulm, Winona and Red Wing.

New Ulm – a southern Minnesota town of 13,000 that wears its German heritage proudly – has a big-city rival in Mankato, about twice the size and just half an hour away, with more shopping choices. About 60 businesses are in the New Ulm program, with about 2,500 active card users, program manager Sheila Howk said.

Businesses choose what percentage of each sale will go toward the program, mostly ranging from 1 percent to 7 percent, though several go as high as 10 percent or 15 percent. ACI takes a slice of each transaction, from less than 1 percent up to 6 percent.

At Kokesch’s store, the normal rebate is 3.5 percent. So if a customer buys a gift for $20 before sales tax, 35 cents would go to the customer’s selected charity and 35 cents would go back on the card to spend later. Kokesch can’t say the project has increased her profit, but more customers are coming through the door.

The biggest discounts in town come at Otto’s Feierhaus, where general manager Marti Bennett offers 15 percent back on traditional German food and pizza, and that goes up to 30 percent during promotions. He’s put his faith in SmartTown to the point that he’s cut back on advertising.

“It’s a high discount, but I think it evens out,” Bennett said.

But Bobbi Fuhr, general manager of a Perkins Restaurant & Bakery, said she’s simply not sure whether SmartTown is paying off. She said ACI’s recent decision to hire someone locally within each SmartTown community to manage and promote the program will help.

“I’ve seen the potential of what it could do, but we haven’t scraped the surface yet,” Fuhr said.

While there’s very little to show that such programs increase loyalty, the charity aspect of the SmartTown program could persuade consumers to splurge a little more on something like dinner in a restaurant if they know part of it is going to a good cause, said Ravi Dahr, director of the Center for Customer Insights at Yale University.

“Anything that can reduce the guilt helps,” he said. “Consumers aren’t consciously aware of this, but we’ve found that it works.”

Deb Herlick uses her SmartTown card to buy gas at the only New Ulm station in the program. She directs the charitable contribution to the Lutheran high school in town; her 18-year-old daughter, Shelby, has hers go toward breast cancer research.

“I think people who don’t normally donate to a cause will do this, because they won’t see the money leave their pockets,” Herlick said.

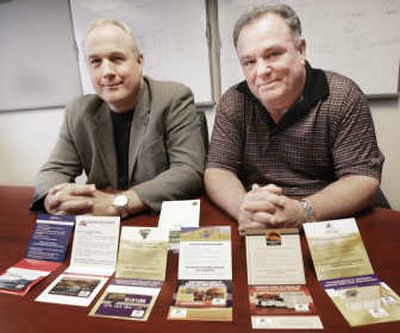

Bouchey and Michael Wheelock, ACI’s executive vice president, said they hope the company can become profitable by building volume with the infrastructure already in place. ACI is rolling out a variation of the card program, called Cash Value, for larger markets. It hopes some bigger retailers will sign on to help expand the program nationwide – but is taking care to make sure the two programs complement each other, Bouchey said.

For the stores, technology has made most loyalty programs relatively inexpensive, said George John, a marketing professor at the University of Minnesota. And businesses may find they have more to lose by not having one, he said.

“It’s hard to make these things work, but you’re kind of trapped because you have to do it to stay competitive,” John said.