Big dose of dollars

U.S. will inject as much as $800 billion to ease credit crisis

WASHINGTON – The government said Tuesday that it will deploy as much as $800 billion to make it cheaper for Americans to get a home mortgage, take out a car loan or borrow money through a credit card, as the government’s intervention in the financial system expands to directly address the impact of the credit crisis on consumers.

The Federal Reserve will launch a program by the end of the year in which it will buy up to $500 billion of securities backed by mortgages, which are guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Fed will also buy up to $100 billion of debt in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which should let them more easily expand their lending.

With the moves, the Fed will be pumping money into the economy through unconventional new means, steps that analysts said should reduce the rates that people must pay to take out a mortgage loan by as much as a full percentage point. In anticipation of the program Tuesday, rates on mortgage securities fell about a third of a percentage point, a drop that is likely to be passed through to borrowers soon.

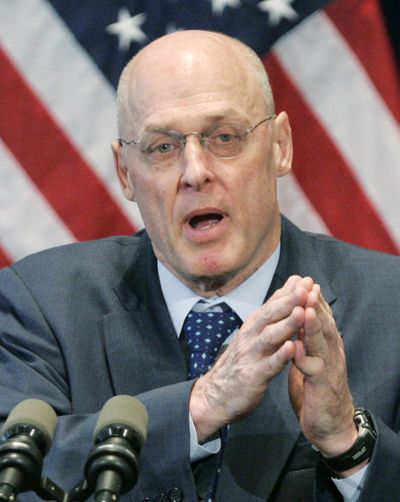

The Fed and Treasury Department, led by Secretary Henry Paulson, are also creating a $200 billion program that will lend against highly rated securities backed by auto loans, student loans, credit card lending and small-business loans backed by the Small Business Administration. Lately, there have been few buyers for packages of those loans, making it difficult for consumers to borrow money.

Previous interventions have focused more on the inner workings of global credit markets – injecting capital into banks, for example, and lending money to large companies. But those efforts have failed to spur the flow of lending to ordinary Americans, contributing to a steep decline in prospects for the overall economy.

Estimates varied on how much the Fed action will lower interest rates for ordinary homebuyers. Jim Vogel, an analyst with FTN Financial, estimated that the Fed’s facility could lower mortgage rates to between 5.5 percent and 5.75 percent for 30-year fixed home loans. Recently rates have been hovering over 6 percent and have been nearly as high as 6.75.

Either scenario would help the economy. It would allow some people to refinance their mortgages, saving money on their monthly payment that they could then use for other things. And it might prompt others to enter the housing market as buyers, helping make the decline in housing less severe.

In a normal recession, the central bank cuts the federal funds rate, a bank lending rate, to encourage growth. Two things are different this time. For one, the downturn appears likely to be more severe than recent recessions. So although the Fed has already cut the federal funds rate to 1 percent – and may well cut it to zero percent by January – it may not be enough.

Moreover, because this downturn is the result of a profound financial crisis that has caused lending to dry up, those interest rate cuts have not passed through to consumers. Since January, the Fed has cut the rate from 4.25 percent to 1 percent, yet the rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage has barely changed.

The major reason is that banks and other financial institutions are suffering huge losses that make them reluctant to lend. So the Fed is effectively printing money and funneling it to homebuyers. In contrast, under previous recent bailout efforts, the Fed has swapped Treasury bonds for other, riskier assets, meaning it was not creating new money.

The Bank of Japan used this latest strategy in the 1990s, but too slowly, according to many economists, creating a downturn that lasted 15 years. The Fed’s actions could stoke inflation in the future, particularly if the Fed is slow to remove the new programs as markets return to normal. But with prices for many goods falling, Fed leaders are more worried about a sharp decline in the economy.

The Fed will only purchase mortgage securities backed by government-sponsored companies Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae, which have high standards for credit quality and caps on how large the loan can be. Because the Treasury took over mortgage-finance giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in September, the government effectively already is guaranteeing the debt of those institutions.