EWU professor digs up ancient history in Cyprus

It helps to record a conversation with Georgia Bonny Bazemore so you can listen to it later with the benefit of Google.

Because you may have forgotten that Adonis was the incestuous lover of Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty and love; that asps are venomous; that Barnabas was an associate of the Apostle Paul. Any of those subjects – heck, all of them – might be delivered in a single paragraph from a woman with blaze-red lipstick and purple-and-jet-black hair.

The discussion will be interrupted by Homeric laughter and peppered with words spoken in Greek – she’s fluent in several dialects and also speaks, reads or writes German, French, Italian, Swedish and some languages lost to antiquity. “Right now, I’m compiling a dictionary of ancient Cypriot terms from a fifth century A.D. Greek dictionary, which has never been translated into English,” said Bazemore, 52, as though she were tackling a bathroom remodel.

She assumes her audience has a rudimentary knowledge of world politics, Middle Eastern geography and Greek mythology. But if she thinks you’re lost, she’s kind enough to pause and ask, “Y’all getting this, honey?” And then you know that Georgia isn’t just her name, and Cheney isn’t her hometown.

Bazemore, a professor of ancient history at Eastern Washington University, was the first in her Deep South family to graduate from high school, and then the first to go to college. Always passionate about history, she did her post-graduate work at the University of Chicago, studying under archaeologists who are well-known by people who know about such things.

And that’s what led her to Cyprus in 1982, into the island’s Rantidi State Forest in 1992 and to EWU in 2002.

Every summer, she leads students to Cyprus, an arid, politically divided island in the Mediterranean, where she’s charged by the Cypriot government to protect and uncover an archaeological site that has known human use since at least 8000 B.C.

Arcadian heroes settled there after the Trojan War, “which is real,” Bazemore is quick to add, in case there’s any question of where she comes down on that particular academic debate. And those heroes worshipped Adonis.

The site, at a spot on the map called Pissoui, is called the Rantidi Forest Excavations, the Sanctuary of Adonis or the shrine of Lingrin tou Digeni. But Bazemore calls it “my sanctuary,” as in “Homer talks about my sanctuary” or “You know the birth of Aphrodite on a seashell? That happened right below my sanctuary.” Or a favorite: “Barnabas cursed my sanctuary” because he caught cult members practicing orgies there.

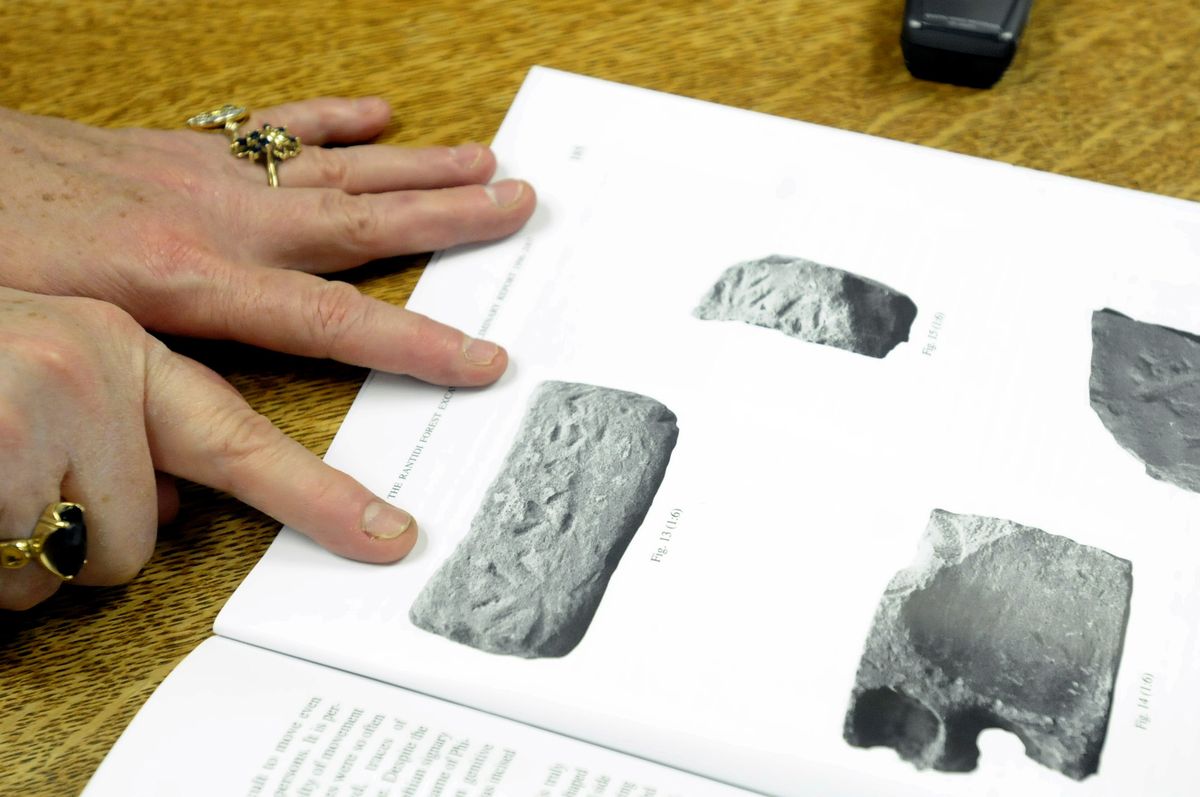

The site of a temple, tombs and terracotta figures, Rantidi had come to archaeologists’ attention in 1909, when inscribed rocks started showing up in local shops, having been hauled to town by farmers. A German archaeologist who explored Rantidi for two months in 1910 declared it the richest site on an island that’s famous for its antiquities.

Over the years, experts from other Cypriot sites would visit briefly and comment on Rantidi’s potential. “But they never, like, told anyone where it was,” Bazemore said with one of her frequent bursts of laughter.

Deciphering inscriptions is her specialty and her passion, so she started looking.

“It took me five days of just walking through this asp-infested brush to find this hilltop,” she said. It had been cleared, plowed and planted for grazing in 1955, and many of its cut stones were piled like rubble.

After four years of fundraising, Bazemore had the necessary $250,000 in backing, and received government approval for the dig. In effect, she was given title to several square kilometers, though the government retains ownership.

But there was a condition: She had to temporarily postpone work on the tantalizing hilltop, starting lower on the slope instead. There, artifacts were hindering development of a golf course and luxury subdivision called “Hills of Aphrodite,” as well as road work.

“It was tit for tat,” Bazemore said. “You do this in order to be able to do what you want.”

The site has been heavily degraded by looting and misuse, and some of the cut rock – including some with inscriptions, Bazemore suspects – went into local lime kilns about the time that others showed up in shops. Limestone erodes easily, so the remaining artifacts haven’t aged well. The tombs sometimes fill with water.

Yet, Bazemore and her students have uncovered hundreds of shards from pottery, figurines and phallic objects. There’s a woman’s chin and mouth that Bazemore describes as “seductive” and believes was part of a statue of Aphrodite. There’s a portion of a deeply grooved male face that Bazemore believes represented the demon god Bes.

There’s a baseball-size jug that dates to 1700 B.C. and contains trace amounts of opium. It was lying right on the surface.

“We were walking along and it’s like, ‘Oops, don’t step on that,’ ” Bazemore said.

Crews cutting a new road last summer uncovered walls from buildings and the bases of terracotta figures that would have been at least as large as actual men.

“I mean, this is an archaeological playground. It’s Disneyland for archaeologists. I’m serious,” said Bazemore, who moved back to the United States shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, and started work at EWU the following year.

Each summer since 1996, and sometimes in the winter, Bazemore has led crews of anywhere from half a dozen students to more than 50. She likes working with students who know “absolutely nothing” about archaeology and have limited travel experience, believing it will benefit them, no matter what they do for a living.

Some of her students become committed to the cause. Her current protégé is Brett Jordan, a graduate student who has spent the past two summers at Rantidi and is Bazemore’s assistant director.

It’s been an unlikely journey for Jordan, who still has the physique that took him to the state track and field championship in 1997, when he was a North Central High School shot-putter. Later, after he failed to master the hammer throw at Washington State University, Jordan attended community college and then transferred to EWU to study history.

“When I first met Dr. Bazemore and she was telling me about Cyprus, honestly, I didn’t know where it was on the map,” said Jordan, 30.

Now, he’s closing in on a master’s degree in ancient history and brushing up on his Greek before applying for doctoral programs. He has no intention of giving up the work at Rantidi, despite the hard digging, the triple-digit temperatures and the high humidity that conspire to take 30 pounds off his frame each summer.

Jordan said holding history in your hands is nothing like reading it in a book. And he’s become fond of the country, its people, its food and its mix of cultures and religions – predominantly Islam and orthodox Christianity.

“Cyprus loves Americans,” Jordan said. “The locals want American universities to come in. They come up and greet us … They invite us for coffee.”

Bazemore hopes to establish an EWU base in Cyprus, perhaps by purchasing a house in a village where the mayor has been particularly inviting. It could be used by archaeology students but also those studying international affairs and a variety of other subjects.

Never one to think small, Bazemore believes Cyprus could help put EWU on the map as the place in the Northwest to go for international studies.

And she hopes the Cypriot government eventually will let EWU borrow some of the Rantidi artifacts so she can start a small museum of archaeology at the campus where the most historic attraction now is a one-room schoolhouse that dates to 1905.