Banks starting to fall in line

Buy-ins give U.S. an ownership role

WASHINGTON – Big banks on Tuesday began signing on to a rejiggered bailout plan that will have the government forking over as much as $250 billion in exchange for partial ownership – putting the world’s bastion of capitalism and free markets squarely in the banking business.

Some early signs were hopeful for the latest in a flurry of radical efforts to save the nation’s financial system: Credit was a bit easier to come by and stocks were down, but not alarmingly so, after Monday’s stratospheric leap.

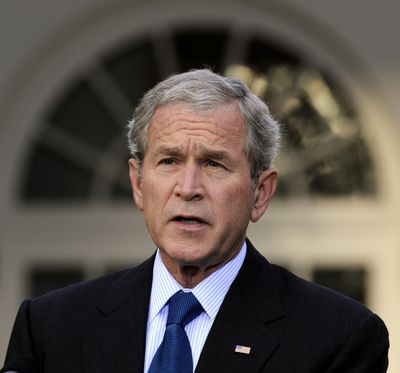

The new plan, President Bush declared, is “not intended to take over the free market but to preserve it.”

The big question: Will it work?

There was a mix of hope and skepticism on that front. Unprecedented steps recently taken – including hefty interest rate reductions by the Federal Reserve and other major central banks in a coordinated assault just last week – have failed to break through the credit clog and panicky mind-set gripping investors worldwide. The Dow Jones industrials declined 77 points Tuesday after piling up their biggest point gain ever on Monday on news of Europe’s rescue plan and anticipation of the new U.S. measures.

Initially, the U.S. government will pour $125 billion into nine major banks with the hope that they will use the money to rebuild reserves and increase lending. Another $125 billion will be made available this year to other banks – if they need it – for cash infusions.

In return, the government will get ownership stakes in the financial institutions. Banks, meanwhile, will have to accept limitations on executives’ compensation.

“Government owning a stake in any private U.S. company is objectionable to most Americans – me included,” Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson said in announcing the initiative. “Yet the alternative of leaving businesses and consumers without access to financing is totally unacceptable.”

Whether the $250 billion will be sufficient to encourage banks to lend again is hard to tell, said Anil Kashyap, professor of economics and finance at the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business. The Treasury Department arrived at the $250 billion figure after consulting with banking regulators.

“This plan will work if we wind up with everybody pretty well capitalized,” Kashyap said. “But if it doesn’t reach that point, we’ll be back in soup down the road.”

The government is counting on banks not to hold on to the cash.

“The needs of our economy require that our financial institutions not take this new capital to hoard it, but to deploy it,” Paulson said.

Treasury switched gears, deciding to first use a chunk of the $700 billion from the recently enacted financial bailout package to pay for taking partial ownership stakes in banks, rather than using the money to buy rotten debts from financial institutions. The government said it still intends to buy bad mortgages and other toxic assets, another move aimed at getting credit flowing again.

Besides the $250 billion this year on the stock purchases, Bush said Tuesday an additional $100 billion would be needed in connection with covering bad assets. That would leave $350 billion of the $700 billion program, presumably to be spent by the next president.

Economists as well as both Democratic and Republican lawmakers on Capitol Hill had urged Treasury to first move forward on the capital injection plan.

The first bank to take advantage of the program was Bank of New York Mellon, which announced it would sell $3 billion in preferred shares to the Treasury. Other banks initially participating include Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America Corp., including the soon-to-acquired Merrill Lynch, Citigroup Inc., Wells Fargo & Co., and State Street Corp.

The government’s cash infusions are attractive to banks because they are having trouble getting money from elsewhere. Skittish investors have cut them off, moving their money into safer Treasury securities. Financial institutions are hoarding whatever cash they have rather than lending it to each other or customers.

Two other initiatives also were unveiled to stem the credit crisis: The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. launched an insurance fund to temporarily guarantee new issues of bank debt – fully protecting the money even if the institution fails.

And, the FDIC will start providing unlimited deposit insurance for non-interest bearing accounts, which are mainly used by businesses to cover payrolls and other expenses. Frequently these accounts exceed the current $250,000 insurance limit, so the expanded insurance should discourage nervous companies from pulling their money out. Both of these efforts would be financed by fees charged to participating financial institutions – not money from the bailout package.

Even if the new plan works, economists caution that it could take years before locked-up lending returns to normal.

The difference between the rate at which banks lend to other banks and the rate at which they buy U.S. government debt has narrowed, but remains near a 25-year high – a glaring sign that there’s still fear in the market. But there was a hopeful glimmer elsewhere: A crucial short-term, bank-to-bank lending rate called the London Interbank Offered Rate, or Libor, inched down Tuesday. That rate is important because a lot of commercial loans and many adjustable-rate mortgages are tied to it.

Some of the banks had to be pressured to participate by Paulson, who wanted healthy institutions to go first as a way of removing any stigma that might be associated with banks getting bailouts. Paulson met privately with bank executives on Monday.

The move, in effect a partial nationalization of the banking system, puts the United States in the awkward position of owning shares in institutions it also regulates. The shares purchased by the government will be nonvoting. They also give the government a priority in getting paid back if a company fails.

So far this year, 15 banks have failed, compared with three for all of 2007.

The economy’s problems also are taking their toll on the government’s coffers. The 2008 budget deficit hit an all-time high of $454.8 billion. The red ink probably will be a lot worse next year as the costs of the government’s rescue of the financial system and the economic hard times clobber the federal balance sheet, economists predict.