‘Common knowledge’

It’s an 87-year-old unsolved robbery and murder – one laced with mystery, gold, racism and, apparently, the power of a badge and judicial robe. Two Chinese brothers – immigrants who mined for gold in the tiny community of Daisy, Wash., on what was then the free-flowing Columbia

River north of Spokane – were assaulted and robbed July 3, 1921.

Wong Fook Ah Nem, who was 69, was fatally shot during a robbery that by today’s standards had earmarks of a hate crime.

His 60-year-old brother, Wong Fook Ah Tai, was tied to a tree, severely beaten, gagged and left for dead. He survived, telling authorities he could identify his attackers, described as two white men.

A day before the murder, the brothers received a note that said, “Last warning China. Leave now,” according to newspaper accounts at the time.

The threatening note was taken as evidence by sheriff’s deputies, the news accounts said, but the murder case file has disappeared – if it ever existed.

Craig Thayer, current sheriff of Stevens County, says his office didn’t inherit any paperwork on the case from his predecessors.

The only official record of the killing that could be found is a copy of a 1921 coroner’s inquest – partially written with fountain pen on onion-skin paper – in the Washington State Archives.

The inquest was conducted, apparently at the murder scene, by Stevens County Prosecuting Attorney Osee W. Noble and county coroner George M. Stapish.

Ah Tai testified he was a short distance from the brothers’ cabin, gathering timber to rebuild a small bridge, when he was tied up, assaulted and robbed of 20 cents.

“Did the men have guns?” the prosecutor asked the survivor.

“Yes, both had two guns,” Ah Tai responded.

It took him some time before he used his pocketknife, not stolen by the robbers, to cut himself loose and walk home in darkness to find his brother fatally shot.

“I went over to him, and I light match and see he shot,” the witness testified.

“I got some medicine and put it on him, on the sore place, and talked to him, called, ‘Oh, brother, Oh, brother.’ Then I walked back and forth, back again to see my brother. I feel his hands. They cold.”

In the middle of the night, he walked a half-mile to a friend’s house to seek help.

“Would you know the men if you saw them again?” the prosecutor asked Ah Tai.

“Yes,” the survivor answered. But there were no follow-up questions, asking him if he knew the robbers’ identities or about the earlier threatening note.

Other details of the 1921 murder exist in old newspaper stories, a couple of personal histories on file with the Colville Historical Society and the book “Pioneers of the Columbia.”

A story published in The Spokesman-Review three days after the murder bore the headline: “Thugs Slay Chinese Miner.”

“Stevens County deputy sheriffs have failed to find the white men in an automobile who shot a Chinaman, Ah Nem, to death two miles north of Daisy …,” the article said.

A July 9, 1921, story in the Colville Examiner newspaper said the crime “is thought by the county sheriff’s office to be one of the most carefully planned robberies and murders in this part of the county in recent years.”

For a handful of elderly former friends and neighbors of the brothers, details of the crime are dimming memories. Tracked down and interviewed this summer, they all told the same story:

Almost nothing was done about the murder of Ah Nem and the assault of his brother, reported to authorities on the Fourth of July. No one was arrested – even though the identities of the suspected killers became “common knowledge” in northeast Washington.

What is now one of the region’s oldest cold cases, they say, was never vigorously investigated, apparently because the suspects were the sons of a judge and a political leader, and the nephews of a Stevens County sheriff who became a prison warden.

The victims apparently were treated like hundreds of other Chinese immigrants who mined and helped build railroads in northeastern Washington: as outsiders, foreigners and, frequently, the targets of racism.

“The Chinese immigrants were treated very poorly,” said Stevens County historian Juanita Bronson. “They had to pay a tax to work that river for gold.”

Priscilla Wegars, curator of the Asian American Comparative Collection at the University of Idaho, agreed.

“All throughout the West, there was a lot of bigotry and racism toward the Chinese,” she said.

After their deaths, 16 years apart, there was “community opposition” to burying the brothers in a “whites only” cemetery at Rice, Wash., the old-timers say.

As a compromise, the Wong Fook brothers were “buried on the other side of the road,” by themselves, away from the graves of white settlers and war heroes, in a remote corner of a small and largely forgotten cemetery on the east bank of the Columbia.

Today, behind a cattle gate and waist-deep weeds at Cully Memorial Cemetery, small tombstones mark the graves of the murder victim and his brother.

Before his recent death, George Cranston Sr. – known as the honorary mayor of Daisy – related details of the murder to his friend, Duane Aldous, a Vietnam veteran, who lives in that area. Aldous calls the case a huge injustice.

“George Cranston told me that he knew a lot about the murder,” Aldous said in a recent interview.

Cranston, who was white, said he became good friends with the Chinese brothers, who sold produce, lily bulbs and firecrackers when they weren’t mining for gold flakes in the Columbia.

Cranston recalled that his friends “the Ledgerwood boys … beat one of them almost to death, and they did kill one, and they did take their gold,” Aldous said.

The suspects apparently were the sons of Robert Ledgerwood, the first mayor of Kettle Falls who later became a judge. Their uncle was Christopher A. “Kit” Ledgerwood, who served as a Stevens County deputy sheriff and the county sheriff before becoming assistant warden at Washington State Penitentiary, according to historical records.

But more than the hearsay account convinced Aldous of the story Cranston told.

“A few years after the murder, sitting around a campfire, one of these Ledgerwood boys pulled out a deerskin gold pouch that he had his tobacco in,” Aldous said. Cranston recognized the pouch as one he’d previously seen in possession of his friend, the murder victim.

“It was the Chinaman’s gold pouch because it was very distinctive, beadwork and stuff,” Aldous said. “George told me, ‘There aren’t two of them like it.’ ”

Cranston’s widow, 96-year-old Lydia Cranston, lives in a group home in Davenport, suffering from age-related memory impairments.

In the presence of her daughter, the elderly woman said she didn’t want to talk about details of the 1921 murder that she grew up hearing about.

“I just blanked it from my memory,” she said, conceding that robbery likely was the motive.

“I think somebody thought they had money, but I don’t know who, and that’s why I won’t say anything,” Lydia Cranston said. “I just don’t know about it for sure. I don’t want to say something that isn’t true.”

But the Cranstons’ surviving daughter, 77-year-old Joayn Taylor, of Davenport, recalls her parents occasionally discussing the murder of a man who’d been a family friend.

“Dad had seen the pouch” in possession of one of the Ledgerwood boys who were his friends, Taylor said.

“He wouldn’t have known about this connection unless he got those details. But I didn’t pay a lot of attention,” she said. “I was more interested in riding horses.”

Stan Clinton, a 91-year-old Spokane resident, also recalls the murder.

Born near Daisy, he grew up fishing near a one-room cabin and small store where the Wong Fook brothers lived on the river – a spot sometimes called “China camp.”

He was only 4 when the murder occurred, Clinton said, but as he grew up he “heard the story” from his late father, Lester Clinton, born there in 1888.

Ah Nem was robbed and killed for gold, the suspects were related to the sheriff, and nothing was ever done because of that relationship, Clinton said.

“That’s my understanding and opinion,” he said. “That story was common knowledge up there. My dad was pretty well respected, and that’s the story he told me.

“The name of the Ledgerwood boys was associated with the murder. I have a hunch that 50 to 100 people knew about it.” Clinton, who moved from his family’s Stevens County homestead in 1935 and later to Pullman, said he had not heard about the victim’s gold pouch turning up in possession of one of the killers.

“It’s the only version that I ever heard – that these two brothers killed him and that, I think, it was their uncle who was the sheriff,” Clinton said. “He was sheriff, so the deal was never investigated.” Clinton said his father “told me that George Cranston knew about it. I think he knew the whole story.”

Over ensuing years, Clinton said, he would occasionally press Cranston for details about Ah Nem’s killers “because I knew he was a friend of the Ledgerwoods.”

“He wouldn’t tell me,” Cinton said. “He just passed it off.”

When he asked Cranston if the killers were related to the sheriff, Clinton said, “he’d just grin and never answer me.”

The same version came from 84-year-old Ines Riley Helmstetter, of Surprise, Ariz. She grew up in the Pleasant Valley, near Rice and Daisy, and spent years tracking local history before writing “And the Coyotes Howled” in 1997.

“It just seemed to be common knowledge that the Ledgerwood boys went in there, robbed and murdered him,” Helmstetter said. “Nobody could do anything because the Ledgerwood boys were related to the sheriff.”

No other suspects were ever identified or mentioned, the author said.

In his 1979 published personal account of life in Stevens County, “The Way It Was,” the late Jack Ledgerwood acknowledged that his father, Cline Ledgerwood, and one of Cline’s brothers were suspects in the murder.

“My father and one of his brothers were blamed for it, but nothing was ever proven,” Jack Ledgerwood wrote, without elaborating.

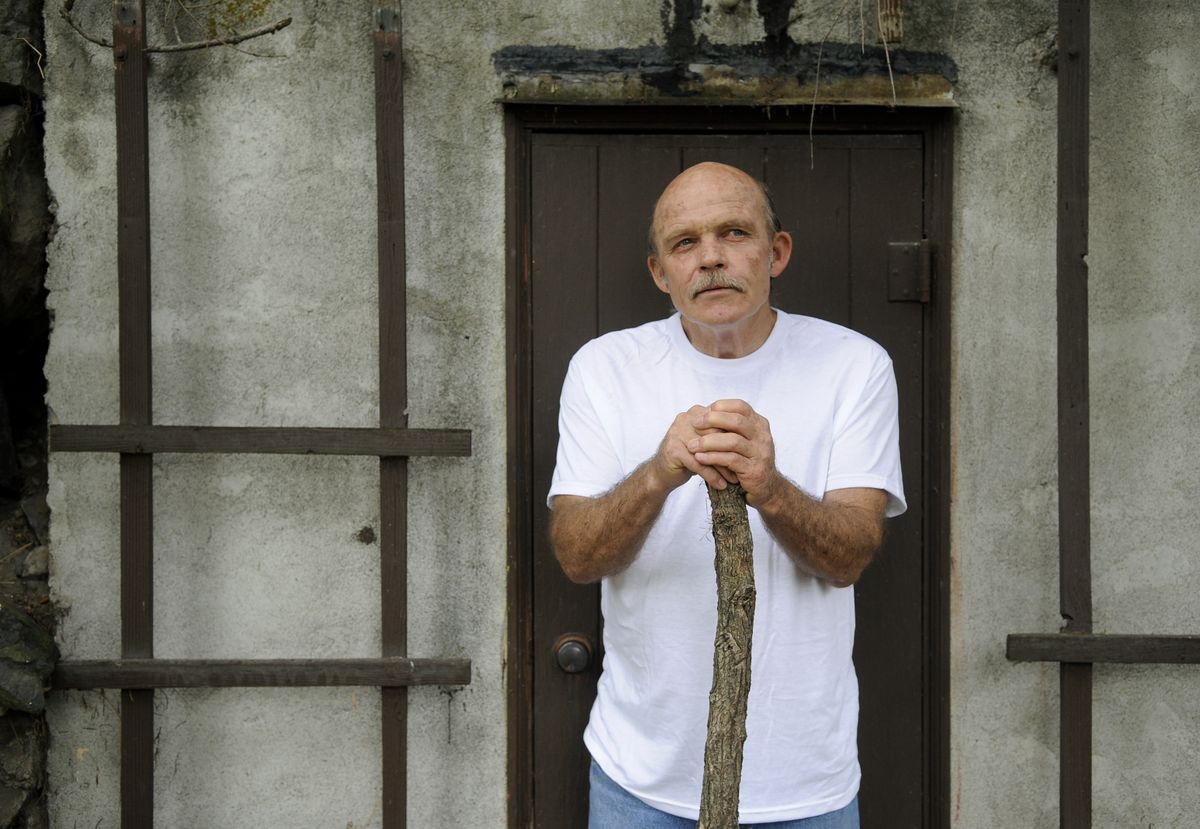

Dennis Sweeney, a human rights activist who lives five miles from the cemetery where the brothers are buried, said although he hadn’t heard of the case until recently, his reading of old news accounts has convinced him that “justice went bye-bye here.”

“My understanding of what I got out of these news stories is these guys were well-loved by a large number of people but were still the victims of racism, and nothing was ever pursued when they were victims of an awful crime,” Sweeney said.

“This is a clear-cut case of justice not being pursued, probably because of the color of their skin. I think it was easier in 1921 to sweep a couple of Chinese immigrants under the rug. Something like this couldn’t happen today.”

This fall, Sweeney said, he will visit the cemetery, just five miles from his home.

“I’d just like to salute these two Chinese guys for how brave they were, living up here in times like that. They should be known, damn it.”