Fast learners

WASL results underscore the effectiveness of English Language Development program

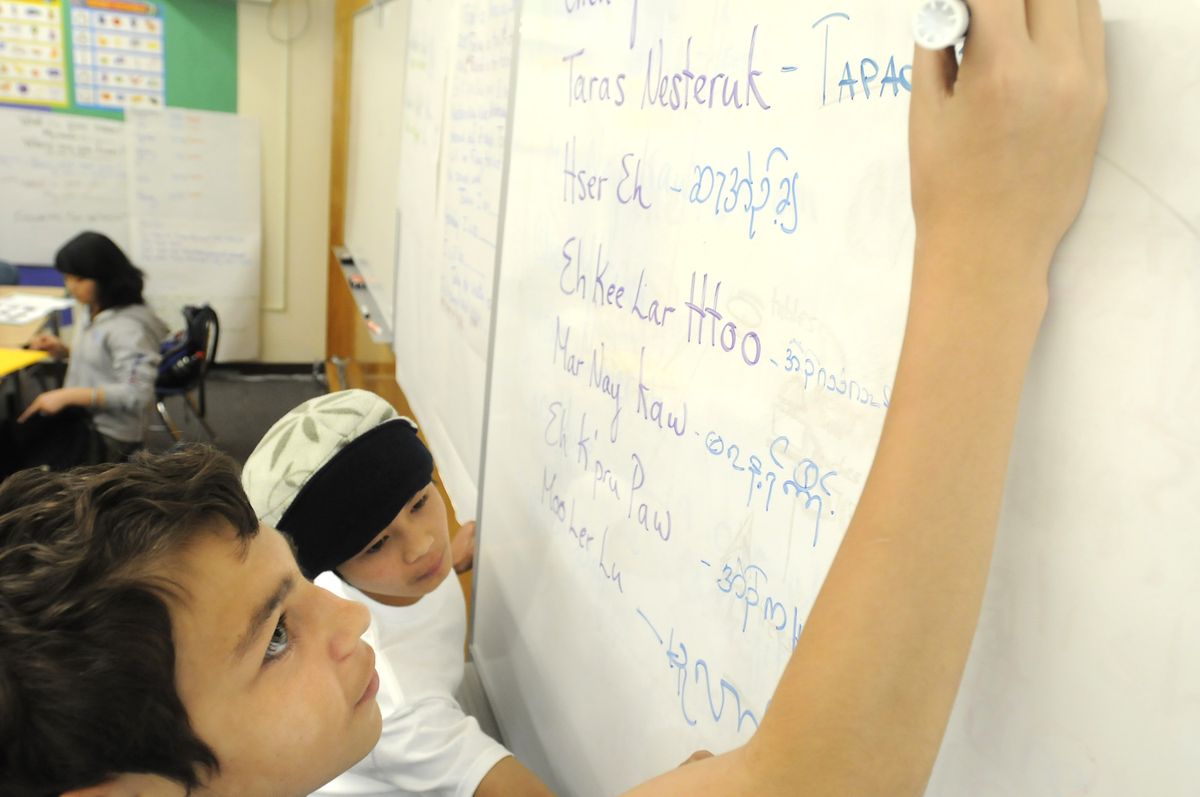

In the newcomer center at Ferris High School, eight students from China, Ukraine and Burma are learning the English nouns and verbs necessary for basic navigation in an alien world.

Teacher Tory Rouse has told them it’s OK to smile in class and to express opinions. She has told them that when an American gives them the thumbs up, it’s not a profane gesture.

Some kids from African countries have to get used to sitting in chairs. Some Eastern Europeans have to be told there’s nothing wrong with sitting on the floor. Some Burmese are fresh from refugee camps and must adjust to just about everything.

In just one semester – long before they’ve mastered the language or American culture – these teens will leave the cocoon of the newcomer center. They’ll get some extra attention from staff in Spokane Public Schools’ English Language Development program, and they may spend a couple of periods a day in classes designed for students still learning English.

But mostly, they’ll be in mainstream classes without interpreters and expected to live up to the same academic obligations as their American-born classmates.

“For some kids, it borders on traumatizing,” said Howard DeLeeuw, Washington state administrator of migrant and bilingual education. “However, the majority do very well; they learn to adjust.”

Very well, indeed.

Among the many WASL details the state recently unveiled was a look at the performance of Spokane students who had gone through the English Language Development program.

In every grade, they performed markedly better than the average Spokane student on reading and math portions of the standardized test.

And the results for reading hold up at school districts statewide, said DeLeeuw, who headed up the Spokane program before moving last year to the state Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Refugee families and other immigrants from struggling countries often have a reverence for education lacking among some native-born Americans, said Phil Koestner, a longtime Spokane Public Schools educator who took over DeLeeuw’s position last year. And they can get one-on-one attention that isn’t always available to native speakers.

But those differences alone cannot account for the disparity, DeLeeuw said.

Rather, he said, the brain is strengthened when a student is thrown into an alien environment, where communication is a constant challenge.

It makes sense to Rouse.

“The WASL really tests a lot of reasoning and problem-solving, and when you see these kids trying to make meaning of conversation with very little English, you realize they’re really working on that problem-solving from day one,” she said.

DeLeeuw started looking at Spokane’s WASL numbers because he wanted to show that immigrants are as smart as others – something that’s difficult to measure until they’ve learned English.

Now, he hopes to use the data to encourage educators and immigrant parents statewide that no matter how much their children struggle at first, the odds are good they’ll excel – if they get the assistance they need up front and are immersed in the dominant culture.

“There was a point for each one of these kids when they were sitting in a class with little English understanding. And I guarantee you that a teacher thought to himself, ‘I’m not sure this kid is going to make it,’ ” DeLeeuw said. “And yet that teacher stuck with it and that effort paid off.”

It helps if their American education starts early, because a full grasp of the language can take three to five years.

Of the 80,000 “English language learners” in Washington schools, about 70 percent arrive during their elementary years. In Spokane, those young students are mainstreamed from the start, Koestner said. They get one-on-one or small-group help from a specialist, but typically for no more than an hour or two a week.

“In that immersion setting they grow really quickly,” Koestner said. “Especially that 5- or 6-year-old because they tend to be more outgoing” than older kids.

Within a few months they’re speaking broken English.

“They learn that playground language really quickly,” Koestner said.

Each spring students take the Washington Language Proficiency test to measure their grasp of English. Those who “test out” no longer receive English Language Development services.

While elementary and middle-school students go directly to their neighborhood schools, all high-school kids spend their first semester at the newcomer center at Ferris, taking Spokane Transit Authority buses from wherever they live in the city. From the beginning all lessons are in English.

“The attendance rates (in the newcomer center) are higher than for other kids. They love it,” Koestner said. “There’s a camaraderie that develops.”

Rouse said one of her Sudanese students last year was so cold she wore a coat nearly every day. But after a winter storm, that girl made her first snowman, with the help of Eastern European classmates for whom snow was nothing extraordinary.

There’s a picture from that day on the wall in Rouse’s class, the tall girl from Africa bundled against the chill, surrounded by kids from around the globe, brought to Spokane by choice or circumstance. In a group picture taken the first day of the year, they had worn nervous smiles. By the time of the storm, they looked happy and settled.

“If a child feels welcome and if the teacher is supportive from the beginning, they’ll do well,” DeLeeuw said.