GM’s road not so smooth

As automaker marks its centennial, it faces its biggest crisis yet

DETROIT – As General Motors Corp. celebrates its 100th anniversary today, the company that was once the nation’s largest employer faces a crisis like no other in its storied history.

GM has lost $57.5 billion in the past 18 months, including $15.5 billion in the second quarter. It’s burning more than $1 billion a month in cash, has more than $32 billion in long-term debt, and a slumping U.S. market has forced it to close factories and shed workers.

In July, it suspended its dividend for the first time in 86 years, and the company has been in perpetual restructuring since at least 2002.

Industry analysts wonder whether GM can make it if the U.S. economy stays in a funk and consumers continue to shun trucks and sport utility vehicles for small, fuel-efficient cars. One analyst even mentioned bankruptcy protection for the company that developed the first fully automatic transmission, the first V-8 engine, the first hydrogen fuel cell vehicle and even the first mechanical heart-lung machine.

“This is the worst crisis they ever have faced,” said David Lewis, professor emeritus at the University of Michigan who taught business history for 43 years until retiring earlier this year. “Because they’re really in danger of failing.”

For all its warts, GM can point to progress, especially on the expense side of the ledger. A historic contract reached last year with the United Auto Workers will save the company about $3 billion per year, mainly by shifting $46.7 billion in retiree health care expenses from GM’s books to a UAW-administered trust in 2010. But the company has to sink more than $33 billion into the trust.

The new contract also includes $14 hourly wages for some new hires, half the pay rate of older workers.

GM has trimmed its U.S. work force and closed factories. In 2006 it had 113,000 U.S. hourly employees; that is now down to about 55,000. Its U.S. salaried work force dropped from 44,000 in 2000 to about 32,000 last year.

While it’s shrinking in North America, GM’s global sales are up 19 percent in the past decade with large increases in emerging markets such as China, Russia, India and Brazil. It’s also spending heavily to become a leader in new technologies, including the Chevrolet Volt electric car due out in 2010.

“We’ve got a very, very good business model now,” Chief Financial Officer Ray Young said in a recent interview. “We’ve driven a lot of efficiency and productivity into our North American operations. We’ve brought down our break-even points.”

Yet critics say GM, since Rick Wagoner became CEO in 2000, hasn’t adjusted quickly enough to its dwindling U.S. market share, which has fallen to about 23 percent this year from a peak of nearly 51 percent in 1962.

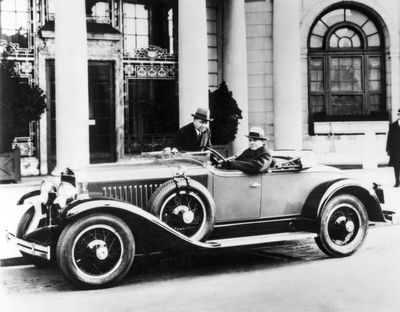

GM’s roots date to Sept. 16, 1908, when Billy Durant started the company with the Buick nameplate. Oldsmobile was added the same year, with Cadillac, GMC and what is now Pontiac in 1909. Durant started Chevrolet in 1911, and Saturn, Hummer and Saab were added as the company grew.

Although it shed Oldsmobile after the 2004 model year, GM still has too many brands and models that overlap, all creatures of a cost structure that’s still too high, said analyst Kevin Tynan of New York-based Argus Research Corp.

Tynan suggests paring the company back to Chevrolet as a mainstream brand, GMC for trucks, Cadillac for luxury buyers – and getting rid of the rest.

“What you’d have is radically different General Motors than we’ve known in these past 100 years,” he said. “There’s definitely buyers for your product globally, domestically,” Tynan said. “Why can’t we just build fewer and be profitable on all of it?”

GM’s history, he said, hurts it in the long run because proud company executives have trouble accepting that market share is likely to drop even further as demand continues to shift away from trucks to cars.

“You get so married to the history that you can’t go forward,” Tynan said. “There’s too many dealerships. There’s too many models and not enough profitability. Unless you address these issues, you’re just going to continue to shrink.”