South Africa’s president to resign

Mandela successor Mbeki out of favor

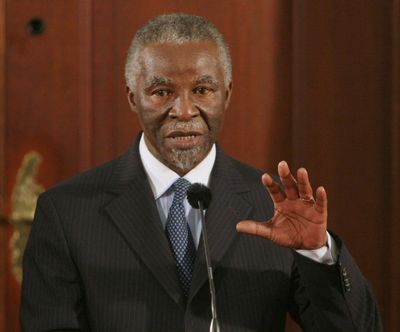

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa – South African President Thabo Mbeki, a former liberation leader and architect of his nation’s post-apartheid democracy, agreed to resign Saturday after the top ranks of his party voted to recall him months before the end of his second and final term.

The party’s decision ushered in a new era of South African politics, as one of its most prominent leaders bowed out of a bitter power struggle with his former deputy, Jacob Zuma, a populist considered likely to win the presidency next year.

The shake-up came a week after a court dismissed corruption charges against Zuma and suggested that Mbeki had plotted to have him prosecuted, a ruling that inflamed divisions within the dominant African National Congress, which Zuma leads.

Gwede Mantashe, secretary general of the party, said at a news conference that the decision was made out of a “desire for stability and for a peaceful and prosperous South Africa.”

Mbeki’s office released a statement saying that he had “obliged and will step down after all the constitutional requirements have been met.”

It was an abrupt end to the presidency of Mbeki, 66, an aloof and scholarly former deputy president who succeeded his boss, freedom icon Nelson Mandela, in 1999. The son of anti-apartheid activists, Mbeki became one himself as a teenager and went on to devote his life to the ANC, including 28 years in exile.

Under Mbeki’s free-market policies, South Africa’s economy maintained a steady growth rate, and a black middle class emerged. Mbeki is credited with advocating African issues on the world stage and with successfully negotiating peace resolutions in Congo, Sudan and, most recently, Zimbabwe.

Yet Mbeki’s policies failed to create jobs or end poverty for millions of South Africans, causing many in his party to lose faith in him. He came under attack for prolonged neglect of rampant violent crime and a glaring AIDS epidemic, and for stifling dissent.

Internationally, Mbeki earned ignominy for questioning the cause of AIDS and for refusing to join other world leaders in condemning Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe’s brutal and ruinous rule.

“The way in which he responded to all these issues was that of a man who is out of touch,” said Aubrey Matshiqi, a political analyst with the Center for Policy Studies in Johannesburg. “Not only out of touch with regard to the rank and file of his own party, but also out of touch with ordinary citizens.”

The tensions combined with rancor over the court case against Zuma, who for seven years has been investigated for corruption in relation to a multimillion-dollar arms deal.

In 2005, Zuma’s financial adviser was convicted of soliciting bribes on Zuma’s behalf. Mbeki fired Zuma as deputy president, a move some analysts say energized Mbeki opponents, who saw him as high-handed and ruthless. Zuma was charged the same year, but the case was dropped on a technicality.

Zuma, 66, staged a political comeback in December, wresting control of the ANC presidency from Mbeki. Days later, prosecutors refiled charges against Zuma, outraging his backers. The tipping point came this month, analysts said, when a high court judge dismissed the charges and suggested Mbeki had been part of a scheme against Zuma. Days later, prosecutors said they would appeal the ruling, a move the ANC decried as an extension of the “relentless pursuit of Jacob Zuma.”

Those events overshadowed Mbeki’s successful negotiation of a power-sharing deal in Zimbabwe.