Attack on Pearl Harbor was a formative event for many

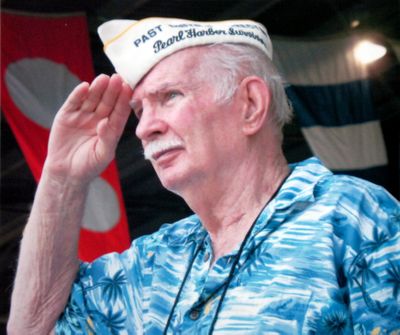

Spokane veteran Jim Sinnott plans to meet with other survivors

The number of Spokane-area Pearl Harbor survivors has dwindled to a handful as the nation marks the 68th anniversary of the attack that propelled it into World War II.

But there was a time, Jim Sinnott recalls, when survivors were so plentiful he had five or six as co-workers at the local Federal Aviation Administration offices.

Meetings of the local chapter of the survivors association would fill his north Spokane basement with music, dancing and reminiscences of that day and the rest of the war. The chapter also held services and laid wreaths for fallen comrades around the anniversary of the attack.

Sinnott, 87 and battling Parkinson’s disease, has cut back on his activities, but today he plans to join seven or eight other survivors who will be honored at a North Spokane Rotary luncheon and hear a presentation about Honor Flight, a group that pays for veterans to travel to Washington, D.C., to visit military monuments.

Most people alive on Dec. 7, 1941, remember where they were when they learned the Japanese had attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Sinnott believes. For those who experienced it firsthand, he said, it may be the most memorable event in their lives. He said he’s seen every movie about the attack – several times – and has an extensive collection of books on the topic.

He was a 19-year-old radio operator at Ford Island Naval Air Station near battleship row who had just come off the graveyard shift. He’d been on island duty less than a month, after serving on the USS Arizona and Tennessee.

“There wasn’t anything unusual that night,” he said. Considering the Japanese fleet was approaching from the north, “it’s surprising there wasn’t.”

He had breakfast and headed back to the barracks to get some sleep. “I was in my pajamas and I heard a plane.” The sound of a plane wasn’t unusual at the air station, but the direction it came from – west to east – was. He went outside, looked up and saw Japanese planes. “They flew over the top of me, so low I could see the faces of the pilots. One of them waved at me.”

The planes continued out to battleship row and bombed the USS California.

Sinnott rushed inside, dressed and reported back to his post. “They didn’t have any work for me; we didn’t have many planes in the air.” He left the radio offices and eventually helped collect the wounded and transport them to hospitals. At one point during the two-hour attack they had to drive between burning planes parked on the air station ramp.

Some of the details are foggy, he said, but “in some respects, it’s like the day before yesterday.”

Sinnott spent the rest of the war in the South Pacific as a radio man on various islands. He’d thought about making the Navy his career when he enlisted, but by 1945 he decided to go back to civilian life.

He was an air traffic controller in Everett when he met Millie, a waitress at a restaurant he frequented. They were married in 1946 and moved every few years to a new controller’s post. They came to Spokane in 1956, and with three children, Millie said she wanted to stay somewhere long enough for the kids to all go through the same high school. They haven’t left.

Around 1960, Sinnott heard about a new organization for Pearl Harbor survivors that had started in California. A small ad seeking interest for a local chapter brought 82 to the first Spokane meeting, some from as far away as Montana. Eventually Sinnott served as its president and the director for the Northwest District, and he helped set up nine chapters around the state.

In its heyday, the Spokane association was so large it lobbied for and received its own spot in the Armed Forces Torchlight Parade.

They were near the front of the procession, Millie Sinnott said. “And everybody clapped for them when they came by.”

The Spokane chapter still meets for lunch once a month, Jim Sinnott said, but “now you’re lucky to get four or five at anything.”