Wet & Wild

Conservation group rallies partners to benefit waterfowl and other wildlife

Wetlands were drained with the good-riddance stature of dirty bath water around the Inland Northwest in the last century. Now some of them are being restored, in bits and pieces, with little fanfare, much as they disappeared.

Spurring the movement are a handful of Ducks Unlimited wildlife habitat biologists who are as adept at leveraging funding as they are at re-wetting the landscape for the benefit of creatures ranging from invertebrates and amphibians to moose.

“I can’t overemphasize the importance of wetlands on the landscape,” said Chris Bonsignore, Spokane-based biologist for the national wetlands conservation group.

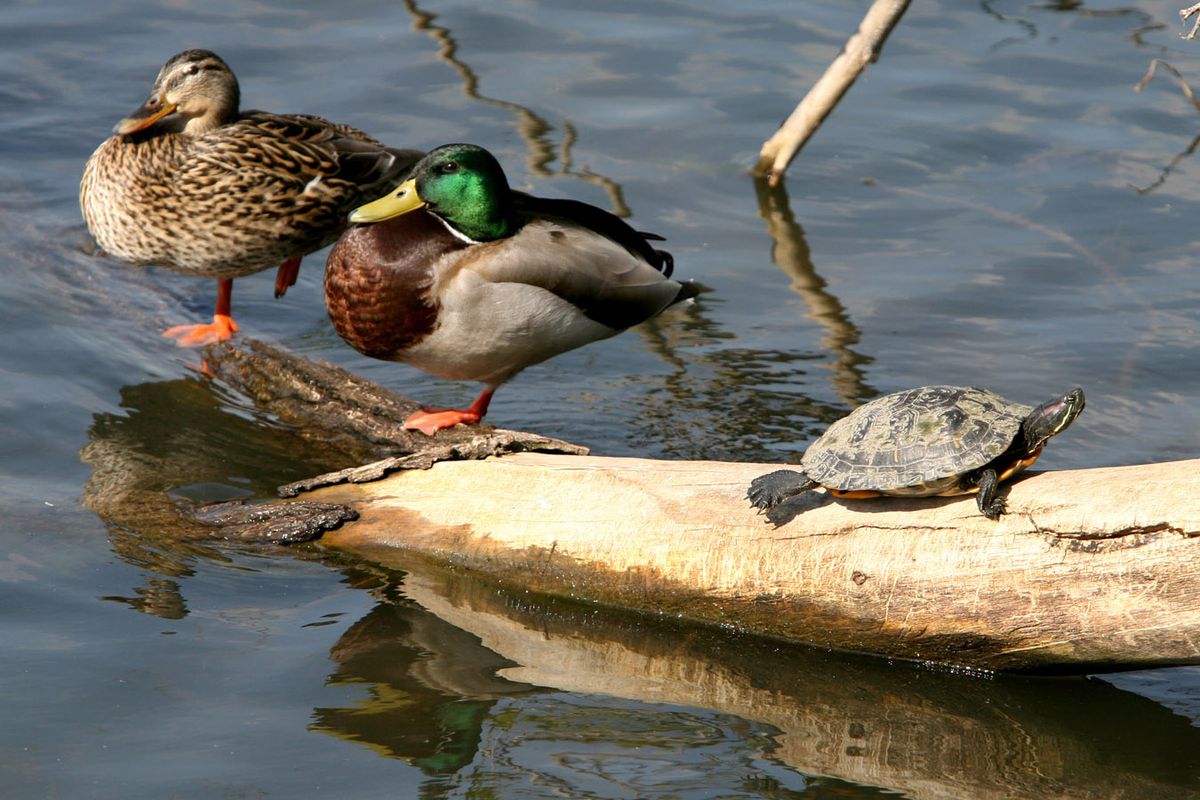

“They’re not just for ducks,” he added, running through a litany of creatures that depend on temporary or permanent wetlands.

Humans are prominently on the list.

People enjoy the wildlife marshes produce, and wetlands also are key to controlling flooding and erosion as well as storing and filtering water for aquifers, Bonsignore said.

DU’s interests aren’t limited to duck hunters, who form the foundation of the group’s 780,000 members.

“Hunting isn’t allowed on all the places we work on,” Bonsignore said. “Most of our members understand that waterfowl production requires wetlands habitat. We’re conservationists as well as hunters.”

Bonsignore and other DU staffers have worked in Eastern Washington and North Idaho with private landowners, local, state and federal agencies, Indian tribes and other conservation groups, such as The Nature Conservancy.

In the past 10 years, DU has helped those partners in this region secure nearly $18 million in funding and provide the technical expertise to complete 99 projects totaling about 36,000 acres.

Overall wetland areas conserved with DU help total 54,800 acres in Washington and 26,350 acres in Idaho, DU officials said.

Bonsignore recently led a field trip for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service staffers and DU volunteers who organize local fundraising banquets to support these projects.

The tour visited three projects that illustrate the variety of partnerships, construction and funding.

First stop was the Slavin Conservation Area, southwest of Spokane and a mile west of the intersection of U.S. Highway 195 and Washington Road. The 628-acre site – prime for both wildlife and development – was purchased in 2000 by the Spokane County Conservation Futures Program.

The deal was sealed for $1.2 million – the land could have earned more by being subdivided and sold for development – when County Parks officials and DU helped the seller obtain $485,000 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which negotiated a protective wetlands easement on 400 acres of the property through the federal Wetlands Conservation Program.

Then the county and DU staffers worked together to leverage that purchase and another acquisition to meet the matching funds requirement for a $978,641 wetlands restoration grant, the largest grant the area had received under the North American Wetlands Conservation Act.

The money has funded several area wetlands projects.

“We never would have received the grant without the county Conservation Futures Program,” Bonsignore said.

In return, the county benefited from DU expertise in recreating a wetland on a vast area of the property’s open spaces that had been drained for producing hay in the heart of the scabland forest of pines and aspens.

“In this case, the job was pretty simple,” Bonsignore said. “Basically, we just had to plug the drainage ditch and ‘Poof!’ we had a wetland the next spring.”

The Natural Resources Conservation Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service paid for heavy equipment to recontour some of the land into natural topography before the flooding.

“DU’s total cost was about $50,000 for the plug installation, which lets us regulate the amount of water on 200 acres of restored wetlands,” he said. “That’s what we call a good cost-benefit ratio.”

In the future, Bonsignore hopes to work with the county to improve the habitat by controlling canary reed grass, which infests many temporary wetlands in the region with vegetation too thick to be of prime use for wildlife.

A private land project was the second stop on the tour to illustrate another type of partnership.

Spokane County residents Darwin and Becky Sciba have been patiently working with Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge biologists and DU for several years to negotiate a conservation easement and wetlands restoration on 45 acres they own.

“Even working with DU, the federal grants took years to obtain,” Bonsignore said. “A lot of landowners won’t wait that long.”

Plugging a drainage ditch last year offered a preview of the benefits last spring when much of the bottomland flooded for the first time in decades.

“It was full of pintails in March,” Bonsignore said.

Refuge staff used heavy equipment this summer and fall to move 23,000 cubic yards of ground and carve ponds that will fill with water next spring.

Much of the scabland bottom will flood year after year to provide resting areas for spring migrants, including swans, Bonsignore said. The newly created ponds will hold water longer and eventually provide nesting habitat.

“This scablands region of Spokane and Lincoln counties is the best of the best for wetlands habitat in Washington,” he said. “It’s just a matter of restoring some of what has been lost.

“We get a bigger return for putting emphasis here because Turnbull (National Wildlife Refuge) is right in the middle of our efforts. The bigger we make the wetlands footprint in this area, the more attractive it will be for waterfowl and other wildlife.”

The last stop on the tour was a project DU helped the U.S. Bureau of Land Management develop in Lincoln County west of Harrington.

DU engineers helped design structures, essentially mimicking beaver dams, to form five ponds and establish 200 acres of wetlands on the creek just upstream from Upper Twin Lake.

The funding trail in this case started with “Duck Stamps” purchased largely by hunters, creating a fund the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service distributes to state wildlife agencies. DU acquired a share of those funds from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to engineer the Twin Lakes project on BLM land.

BLM has become an especially attractive partner for Ducks Unlimited as it has consolidated big tracts of land in Lincoln County over the past 10 years, Bonsignore said.

“A lot of the scablands have been altered over the past 100 years,” he said. “With BLM consolidating large parcels, we can start to have a difference on thousands of acres. We can more freely restore some areas without some of the limits you have on smaller parcels.”

In the past five years, DU and BLM have restored more than 1,300 acres of wetlands in four channeled scabland projects, he said.

Similar partnerships have been formed with Indian tribes, most notably the Yakama Nation.

The Nature Conservancy has been a major partner on large land holdings secured for conservation along the Kootenai River in North Idaho, he said.