Utah’s deep-coal operators face heavy regulation

HELPER, Utah – Two years after a Utah mine collapsed, entombing six miners more than 2,000 feet under a mountain and killing three members of a rescue team, the state’s coal operators are backing away from rich coal reserves held deep under the ground.

Coal mines have come under intense scrutiny in every part of the country, with the Mine Safety and Health Administration tripling fines against all coal mines last year, to $152.7 million.

But in Utah, where easy access to coal was exhausted more than a decade ago, operators say they have been hit especially hard because of the extreme depths at which they dig for coal.

The risks are compounded by a common method of coal removal called retreat mining, which has operators sometimes flirting with disaster by deliberately inducing cave-ins.

The Crandall Canyon collapse in 2007 shows what can go wrong.

A bounce, a type of seismic jolt, imploded with the force of two million pounds of explosives at Crandall, said Michael McCarter, a professor of mining engineering at the University of Utah.

The tremor flattened a section of the mine roughly the size of 63 football fields, leaving six miners entombed 2,160 feet under mountain cover. Another cave-in 10 days later killed three members of a rescue team, including a federal mining inspector.

Federal regulators, stung by criticism following mine disasters from West Virginia to Utah, quickly clamped down.

“We’ll never know if we make the right decision – we’ll just know when we make the wrong decision,” said Kevin Stricklin, coal-mining boss for the Mine Safety and Health Administration.

But with federal inspectors on site practically every day, executives for several Utah mines grumble that the inspectors are writing up citations mostly for small offenses – a pile of coal dust there, a spill of grease here.

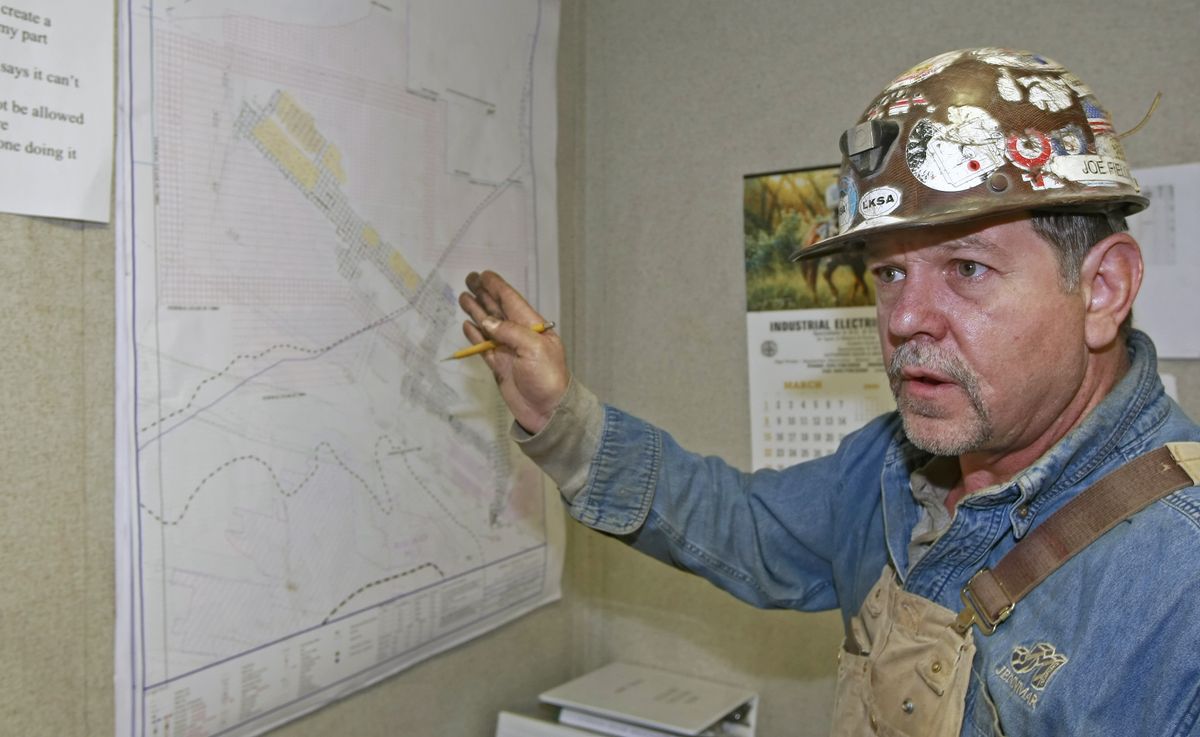

About 30 miles away from Crandall is the Horizon mine, operated by American West Resources Inc.

Horizon was put on a special watch with twice the national average of safety violations.

So to appease regulators, Horizon retreated from a section of its mine that logged 26 roof falls over the previous two years.

The section contained 300,000 tons of high-quality coal and easy access to millions of tons more.

“We’re a small company, and we made a hard decision,” said Dan Baker, chief executive officer for Salt Lake City-based America West Resources Inc., a public company. “I don’t know how many millions of dollars went into developing that section.”

Other companies are following suit.

Utah’s largest coal operator, St. Louis-based Arch Coal Inc., turned away from a deep coal seam at the Dugout mine in central Utah, leaving behind 4 million tons of coal a year ago.

McCarter and other mining experts question whether regulation has gone too far.

Mining authorities ordered a new method of longwall mining that effectively cuts West Ridge’s reserves in half, “and I’m not really sure anybody has proven it any safer,” McCarter said.

The cave-ins are part of everyday deep mining, McCarter said. Two common methods of coal removal, longwall and retreat mining, depend on orderly, controlled cave-ins for safety.

But federal officials say the size of the Crandall Canyon disaster showed more scrutiny was needed.

“In the past, anything an operator submitted – if it was a reputable operator – we took their word for it,” Stricklin said.

Others agree the tighter regulations are a welcome change, because mining companies for years got a free pass.

“It was a rubber stamp,” said Mike Dalpiaz, the mayor of Helper and a United Mine Workers of America vice president. “We had to spill blood before they started paying attention.”

Miners are paid well for the dangerous job – around $65,500 a year, double the region’s average wage, according to the Utah Department of Workforce Services

About 4,000 feet inside Horizon via a honeycomb of sloping tunnels, Dallen McFarland used a cable-connected joystick to finish boring a tunnel with a 50-ton cutting machine.

He didn’t flinch when the walls – miners call them ribs – started making noises like a knuckle cracking, with the weight of 800 feet of mountain cover bearing down.

“When your ribs are popping, that’s good because it means they aren’t storing energy,” McFarland said.