In flood of goodbyes, one rings most true

Jackson memorial rife with songs, pageantry

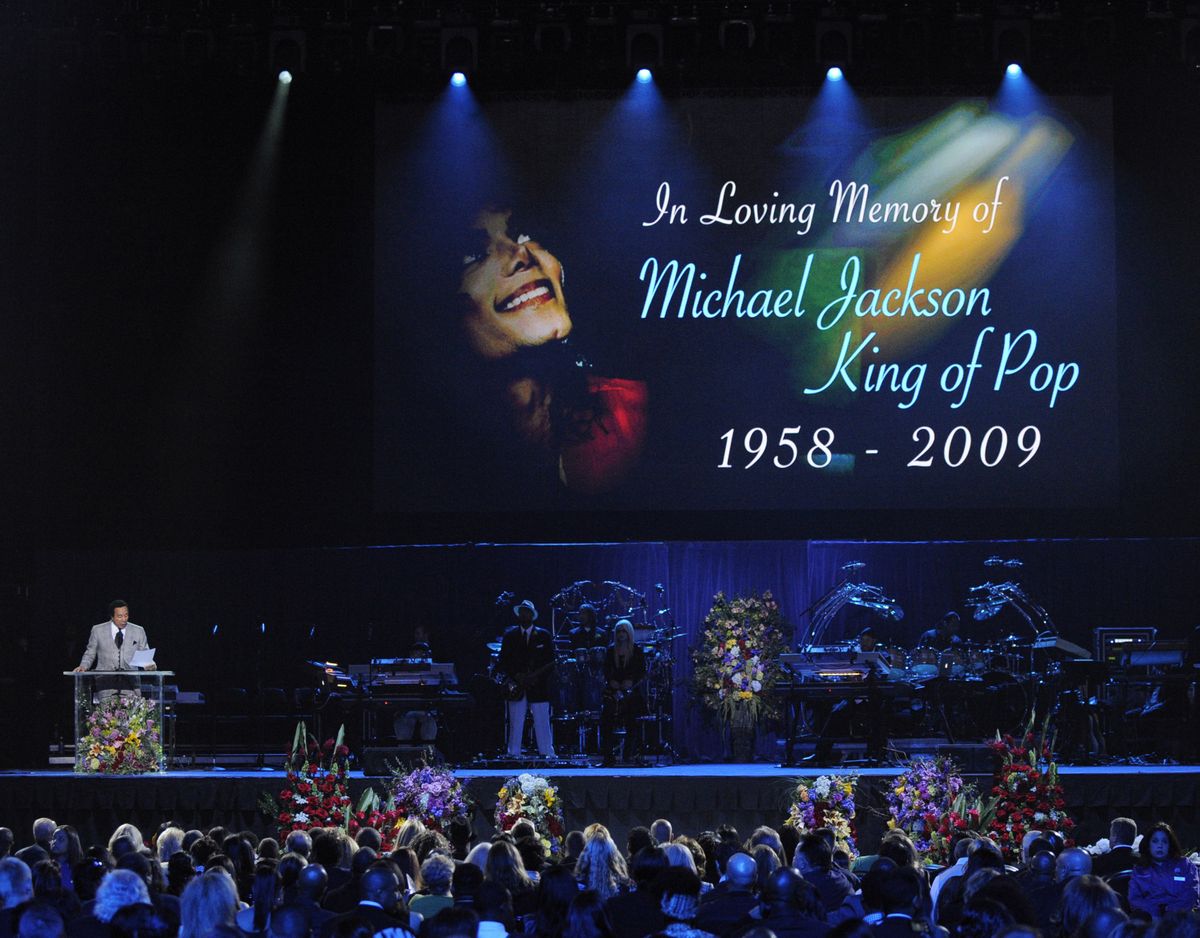

The final, posthumous performance of Michael Jackson was in the transcendent tradition of his previous shows: part musical feast, part religious experience, part examination of a man who seemed like something else his public was always trying to figure out. Boy? Demigod? Alien? It was, at times and fittingly, odd. There was deep, heartfelt, intimate emotion at the public memorial, but it was mixed with the fantasy and the sequins and the Mariah Carey and the Al Sharpton.

It was very sad. It was very long. “Maybe now, Michael, they will leave you alone,” Jackson’s brother Marlon said into a microphone at the end of the nearly three-hour remembrance and farewell. Maybe not. News reports have warned of impending legal battles and estate divisions and custody arrangements. The world will be breathing Michael Jackson gossip for a long time. But in a society obsessed with closure, this occasion at least signified the official end of the country’s 12-day period of frenzied mourning, and the completion of Michael Jackson’s 12-day transformation from ostracized to beloved.

The nationally televised memorial took place Tuesday morning at Los Angeles’s Staples Center, where as recently as the night before his June 25 death the singer had rehearsed for a planned London comeback tour.

The public event immediately followed a private family service at Forest Lawn cemetery in Hollywood Hills, and a long, slow funeral procession through the streets of L.A., which was commented on by swarms of news crews hovering in helicopters. The cavernous Staples Center was filled with the 17,000 fans who won a ticket lottery entered by 1.6 million people for the privilege of being there. They were given wristbands.

“I couldn’t believe when he died,” said John Castanon, 60, a mechanic from San Dimas whose wife had won two passes to the memorial. He fought back tears as he described seeing Jackson perform in 1969. Castanon said he was honored, 40 years later, to be at Jackson’s final appearance.

Everyone wanted to be there. Celebrities turned out en masse, for a starry program that included everyone from Motown record producer legend Berry Gordy to Queen Latifah to Kobe Bryant to Martin Luther King III and U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas. Diana Ross and Nelson Mandela couldn’t make it, so they sent words of sympathy through an emissary, Smokey Robinson, the first speaker on the program.

Jackson’s wall of brothers, seated in the front row next to his parents, sisters and three children, all wore matching yellow ties and single sequined gloves.

Jesse Jackson was there, as were Dionne Warwick and Spike Lee and Barbara Walters.

Once all of the guests, famous and non-famous, were there and seated and hushed, Michael Jackson himself arrived, in an ornate gold casket draped in flowers and brought to a position of prominence in the center of the stage.

And thus Jackson became a part of his own memorial, a showman even in death.

What a spectacular show it was, performed against a backdrop of simulated stained-glass windows and drifting clouds.

Carey, wearing a long gown with a plunging mesh neckline – demure, for her – performed her version of the Jackson 5 hit “I’ll Be There,” and looked meaningfully toward Jackson’s casket.

The musician Usher also looked toward Jackson’s casket during his song, then walked toward it and placed his hands on it.

Jennifer Hudson did not interact with the casket but sang a from-the-gut version of “Will You Be There,” accompanied by a troop of backup dancers. Somber, funereal backup dancers, yes, but backup dancers nonetheless. No one tried to moonwalk. It would have seemed disrespectful.

Was this a concert or a memorial? An arena or a church? The mood of the fans alternated between celebratory and morose, interrupting moments of silence to scream, “We love you, Michael!” and gasping, “Oh my God, it’s him!” when the casket appeared. These fans, the true believers who stuck by Jackson through the trial, through scandals, through failed marriages, seemed desperate for reassurance that their adoration had not been misplaced, that Jackson was as brilliant as they knew him to be.

They cheered loudly when Gordy decided that the title King of Pop was simply not grand enough for Jackson. “I think he is simply the greatest entertainer that ever lived,” Gordy said. Similar calls of approval came after Queen Latifah asserted confidently: “Michael was the biggest star on Earth.”

The biggest cheers and sighs did not come not after the platitudes, or the superlatives, or even the Jesus-like comparisons to the divine (“As long as we remember him, he will be there forever to comfort us,” said Pastor Lucious Smith). The biggest cheers came after the assertions that he was just like us, that he was not weird at all. He liked Kentucky Fried Chicken, Magic Johnson revealed. The audience liked hearing that.

“There wasn’t nothing strange about your daddy,” Sharpton said, thunderously addressing Jackson’s children. “It was strange what he had to deal with.” The stadium erupted with a standing ovation.

But Michael Jackson was strange. His mystery is as much a part of his legacy as his music; fans will forever be picking away at him, trying to understand him. How desperately they wanted to understand him, to understand whatever physical ideal he felt he was moving toward, even as his pursuit of it took him further from normalcy.

His transformation of his own face took more than 20 years, as did his journey from beloved, giggling child star to bizarre, fragile child-man.

The public’s transformation of Michael Jackson, from mutant to messiah, took less than two weeks. “Michael … made us love each other,” Sharpton called out. “It was Michael that made us … feed the hungry.”

It was an orgy of praise, an exercise of excess and quantity, much like Jackson’s life.

And then, at the end of the memorial, another kind of moment.

It happened after all of the Grammy winners had performed, and all the famous guests had ascended to the stage for a big group-sing of “We Are the World.”

Jackson’s 11-year-old daughter, Paris Katherine – heretofore mostly hidden from the public eye – was shepherded to the microphone by a phalanx of Jackson’s siblings.

“Daddy has been the best father you could ever imagine,” she said, her voice breaking. “And I just want to say I love him so much.”

The moment felt pure and private, the truest thing in the whole show.