Famed dancer Cunningham dies

Choreographer pioneered works without story, music

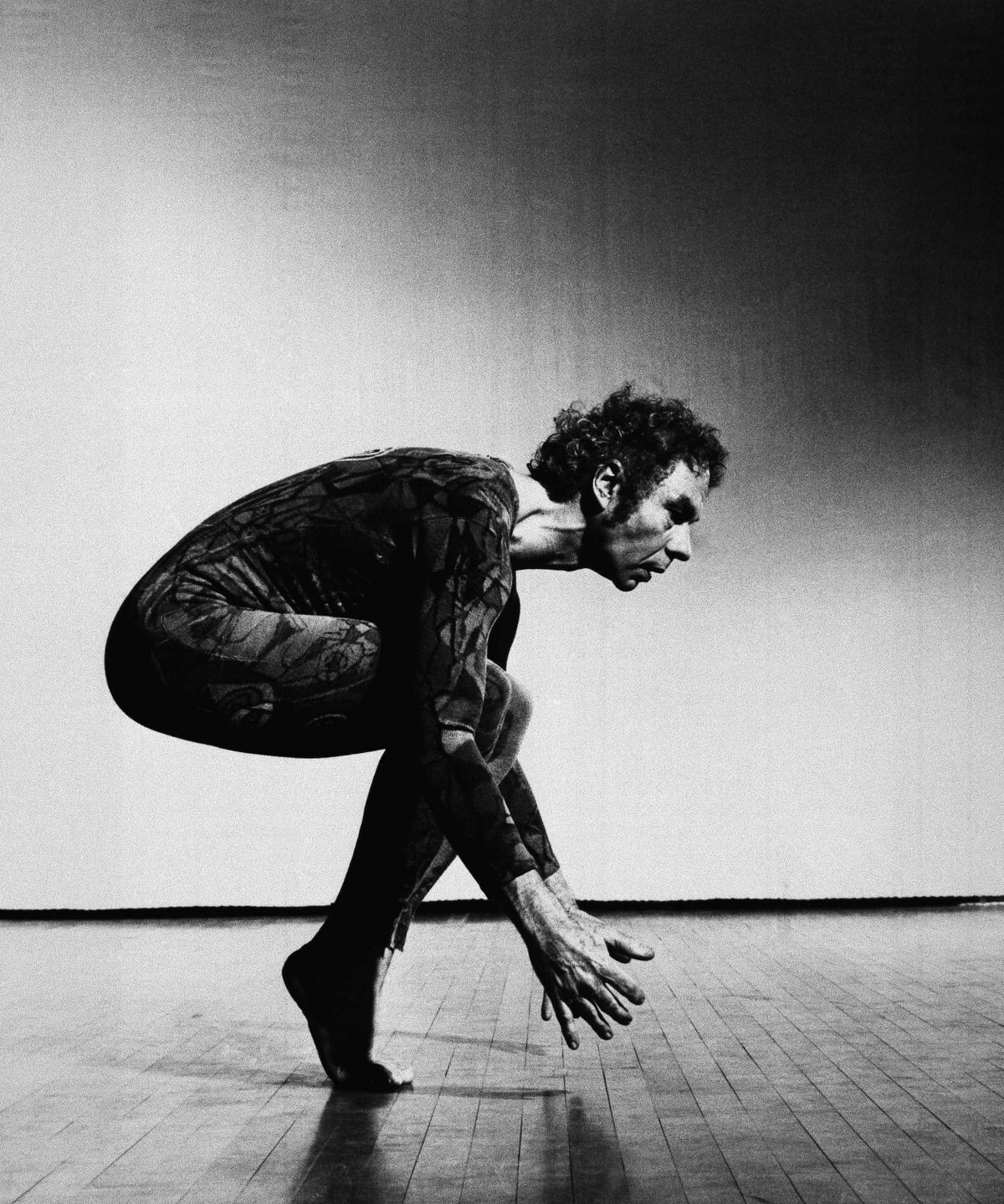

NEW YORK – Choreographer and dancer Merce Cunningham was hailed Monday as a revolutionary artist who remade the very definition of dance.

Cunningham – who was still working as he marked his 90th birthday just 3 1/2 months ago – died Sunday at his Manhattan home, said Leah Sandals, spokeswoman for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. She said he died of natural causes but declined to elaborate.

The one-time Martha Graham dancer was credited with remaking modern dance by creating works of pure movement divorced from storytelling and even from musical accompaniment.

“I’d rather find out something than repeat what I know,” he once said. “I prefer adventure to something that’s fixed.”

In a career that spanned more than 60 years, Cunningham determined steps by chance – saying it freed his imagination – and shattered unwritten rules such as the need for dancers to face the audience and keep time with the music.

Reacting to his death, the great New York City Ballet dancer Jacques d’Amboise said Monday that Cunningham “made everybody rethink what is dance: Is it just movement to time? Does it have to be synchronized? Can it be improvised? Can it be spontaneous? He played with all these ideas.”

Cunningham worked closely with composer John Cage, his longtime partner who died in 1992, and with visual artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. But, he said, “I am and always have been fascinated by dancing, and I can just as well do a dance without the visual thing.”

Other choreographers have made plotless dances but Cunningham did his even without music. The audience got both dance and music, but the steps weren’t done to the music’s beat, and sometimes the dancers were hearing the music for the first time on stage.

His dances may have been nontraditional, but the intricate choreography wasn’t easy to do, and his dancers were all highly trained. Cunningham himself continued to dance with his company well into his 70s.

Among his creations – more than 150 in all: “Sounddance,” 1975; “RainForest,” 1968; “Septet,” 1953; “Exchange,” 1978; “Trackers,” 1991; “Pictures,” 1984; “Fabrications,” 1987; “Cargo X,” 1989; and “Biped,” 1999.

“Merce saw beauty in the ordinary, which is what made him extraordinary,” said Trevor Carlson, executive director of the Cunningham Dance Foundation. “He did not allow convention to lead him, but was a true artist, honest and forthcoming in everything he did.”

He had recently set up the Merce Cunningham Trust, and planned that his dance company would have a two-year tour and then shut down. The Cunningham Trust would preserve his choreography for future artists, scholars and audiences.

“My idea has always been to explore human physical movement,” Cunningham said in June. “I would like the Trust to continue doing this, because dancing is a process that never stops, and should not stop if it is to stay alive and fresh.”

Among the honors that came his way over a long career were the Kennedy Center Honors, 1985, and the National Medal of Arts, 1990.

Merce Cunningham was born in Centralia, Wash., the son of a lawyer. He studied tap and ballroom dancing as a child, then attended the Cornish School, an arts school, in Seattle after high school.

In a 1999 Public Broadcasting Service interview, he recalled that he wanted to be an actor and took dance just to help him act better.

The school director was making out his schedule, and “she said, ‘Well, of course, you will do the modern dance.’ And I didn’t know one from the other. So I said, ‘All right. … It’s chance.’ And in the end, I think for me it was very good chance.”