Reporting for diploma

Al Malmo graduates after 40 years

East Valley High School senior Al Malmo will graduate a month and a half after his retirement.

At 62, Malmo will definitely be the oldest participant in the school’s senior breakfast and commencement on June 15.

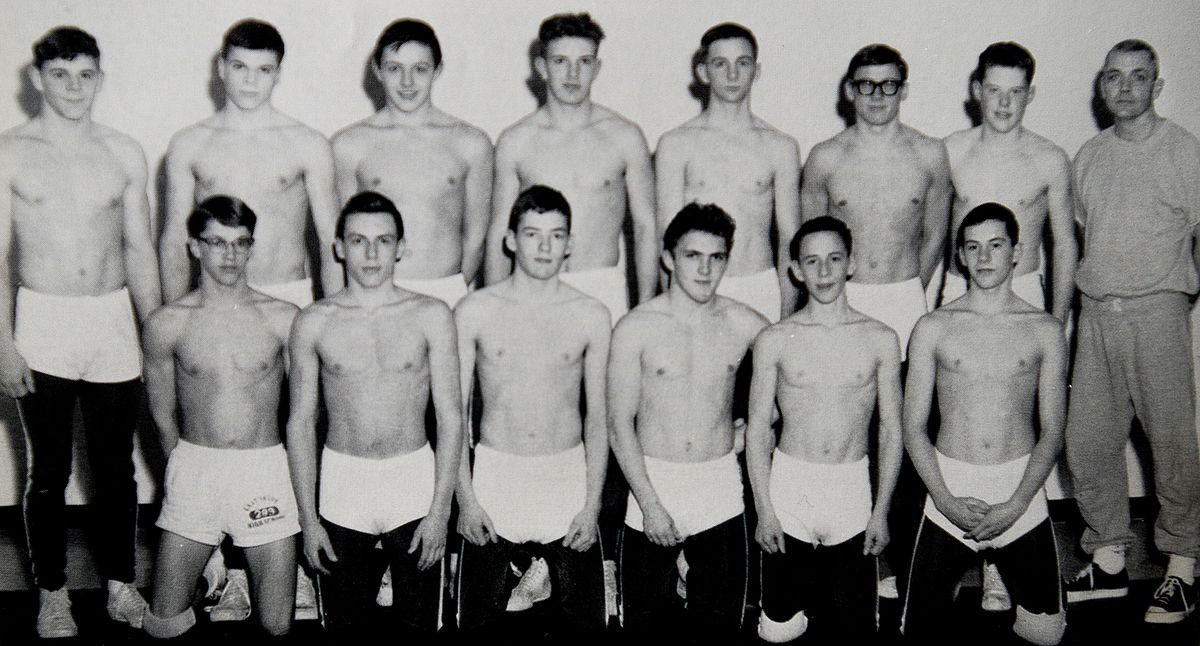

Malmo was just a few months away from graduation in 1966, 43 years ago, when he enlisted in the Marine Corps. He will get his diploma under a federal law that allows delayed graduation for high school students whose education was interrupted by military service.

Finally receiving his diploma will be “quite an emotional deal for me,” Malmo said. “I’m looking forward to that.”

He’s also looking forward to the senior breakfast at Old Country Buffet, but plans to take a pass on the all-night party – “unless they need me as a chaperone. That would be fun.”

Malmo said he’s grateful for the welcome he’s received from this year’s seniors, but he’s not trying to be one of them. He’s marching for fallen servicemen and for would-be dropouts.

“The thing I want to emphasize is the solemn commitment that I have to do this graduation procedure for the young men that can’t do it or the ones that are out there and could do it and should do it,” he said.

To anyone thinking about dropping out, Malmo says, “You’ll regret it for the rest of your life.”

He has.

“Pull yourself up and get yourself in class,” he urges. “The things that are happening in your home lives and among friends can’t be as bad as being left behind.”

Malmo thinks his grades probably were good enough for him to graduate in 1966, but he quit trying.

“I was missing school and stuff due to home life and things like that,” he said. “Things got a little rough monetary-wise. There were six of us kids, and food was getting scarce at the time.”

So, despite the intervention of counselor Carl Canwell – for which he is still grateful – Malmo dropped out and joined the Marines.

“I wish I would have been wide awake,” he said. “I wish I didn’t have my head on my desk. I sat next to a guy at East Valley High School that went to West Point.”

Malmo went to San Diego, where he felt his first tinge of regret. He felt “left behind” by his high school classmates, but was determined not to be left behind in the boot-camp races that weeded out unsuitable recruits.

“That Marine Corps hurdle was a rough one,” he said, but he was selected for “sea school” and graduated second in his class at the Coronado Naval Air Station.

Malmo went on to serve as an orderly to captains and admirals before his discharge in December 1969. Much of his service was at the Coronado base, but he did two six-month tours in Vietnam, shuttling among warships with the senior officers who commanded them.

He acknowledges a Forrest-Gump quality to his experiences, in which an obscure person’s life transects the momentous events of a tumultuous era.

Like many in his generation, Malmo remembers exactly where he was when President Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963 – in an English literature class – in what arguably was the beginning of the end of innocence.

“When I was in high school, we didn’t even know how to spell marijuana,” he recalled.

In those days, students misbehaved with a flask of booze. Well, there also was that motorcycle someone drove down the hall of East Valley High School, Malmo said.

Change came quickly.

While stationed in California, Malmo toured the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, where everyone knew how to spell marijuana.

“I felt sad for my generation from that,” Malmo said.

Also while he was at the Coronado Naval Air Station, Malmo was part of a detail of servicemen assigned to help move Rear Adm. George Morrison’s son out of the family home. It wasn’t until later that Malmo realized the son was Jim Morrison, lead singer of The Doors.

“Here we were all in uniform and he was completely counterculture,” Malmo said. “I think his dad was trying to send him a message.”

He said Jim Morrison seemed “stern, almost like he was being thrown out of his father’s house.” The elder Morrison later was quoted as saying his son “knew I didn’t think rock music was the best goal for him.”

During his Vietnam tours, Malmo met the war’s supreme commander, Gen. William Westmoreland, and South Vietnamese Premier Nguyen Cao Ky.

Ky “had a swagger stick and an ascot around his neck, the whole thing,” Malmo said. “He kind of reminded me of a Vietnamese Patton.”

Flamboyant World War II Gen. George Patton packed a pair of pearl-handled revolvers as his trademark.

During port calls to Japan, Malmo recalled some 50,000 anti-nuclear protesters surrounding the Sasebo Naval Base.

“It was scary until the Japanese Imperial Police got things under control,” he said. “There were stories of them throwing acid.”

Nevertheless, Malmo got on a bus alone and went to Ground Zero of the atomic bomb blast in Nagasaki, where he felt out of place.

“People were staring at me,” he recalled. “It was almost like holy ground to them. That was sobering.”

Not long after that, on Jan. 23, 1968, North Korea seized the USS Pueblo surveillance ship and Malmo went to the North Korean coast as part of an American show of force.

After his discharge, Malmo worked at a variety of jobs in Renton, Wash., and Spokane. He built railroad cars, arranged store displays, drove trucks, was a warehouseman and worked for companies that made spas, safes and cardboard boxes.

Although he might have earned more with a high school diploma, he regrets only the sense of failing to live up to his own expectations. He wishes he had gone to college and now is thinking about taking some classes.

Malmo won’t have to go far to pick up his diploma. He lives about a mile and a half from his soon-to-be alma mater.

His wife, Tina, also attended East Valley schools and their son, 11-year-old Clifford Malmo, is a student at Trentwood Elementary.

Al Malmo’s three other children, from a previous marriage, are in their mid- to late 30s. Two of them, Eric and Hallie Ray Malmo, live in the Spokane area, and Mark lives near Tacoma.

Far from giving his father a hard time about his belated graduation, Clifford “thinks it’s the greatest thing,” Malmo said.