Memento of WWII reaches soldier’s son

Found on a tiny island, dog tag was passed from hand to hand

John McGrath came home to Spokane at the end of World War II after nearly five years in the Army. One of his dog tags didn’t.

It was left on a tiny island almost half a world away, one of several stops in the South Pacific his Spokane-based National Guard unit made after being called up to active duty in 1940.

The dog tag turned up too late to be returned to McGrath, who died in 1986 of cancer. But through the efforts of a former Marine who was given the tag last fall, his youngest son, Tony McGrath, recently received a tangible piece of his father’s history to add to a small collection of mementos.

“There’s not a whole lot left,” Tony McGrath said after receiving the military ID tag sent to Spokane by Shane Elliott, of Burlington, Wash.

John McGrath earned a Silver Star and at least two Purple Hearts for actions with the 161st Regiment in the South Pacific, but most of his service mementos, including the Silver Star and a Purple Heart, were stolen in a burglary years ago, Tony McGrath said.

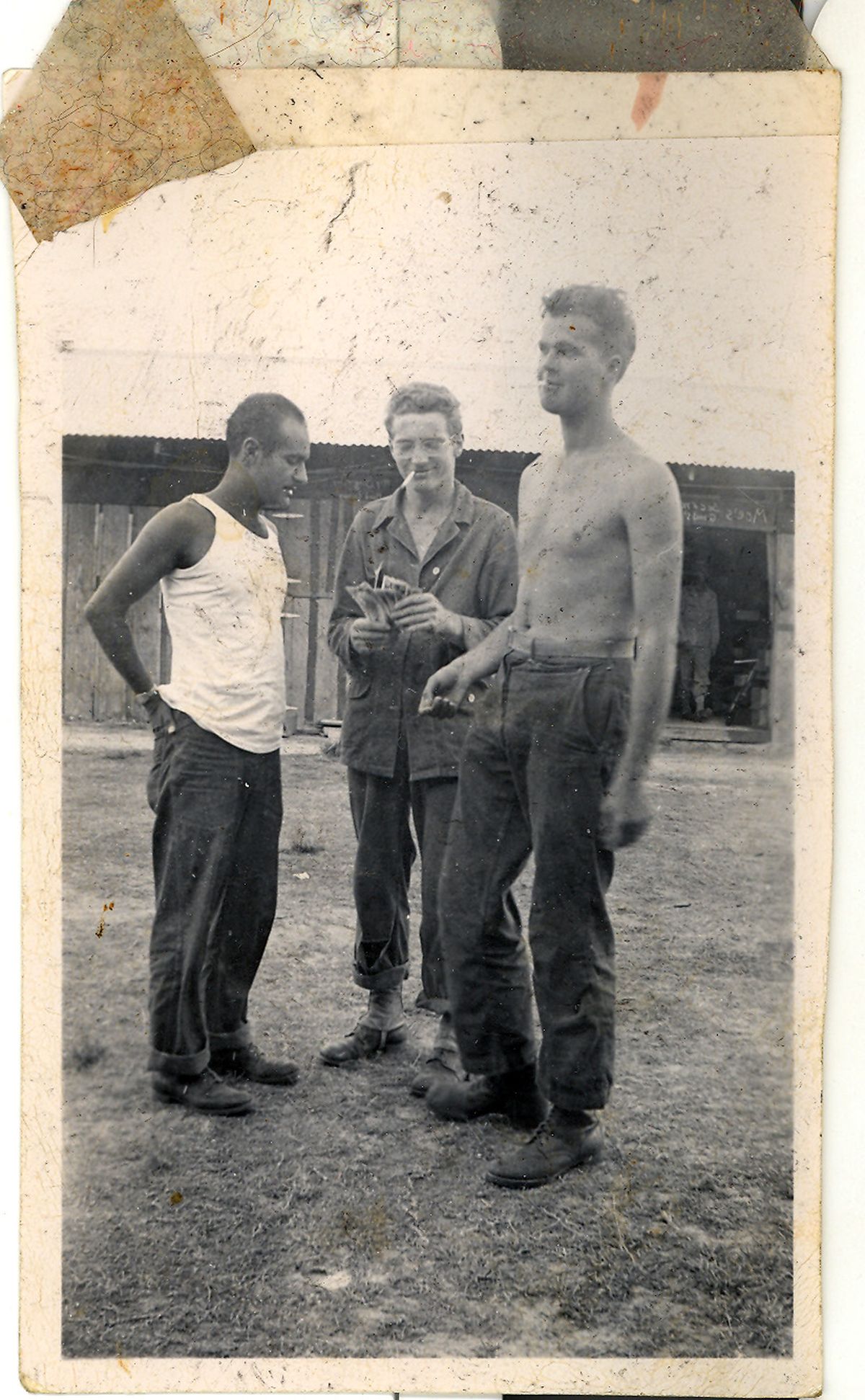

Tony, a Spokane Valley resident, still has a few black-and-white photos from his father’s days in the military, part of one Purple Heart – the medal minus the ribbon and pin – and the yellow-on-red “Tropic Thunder” shoulder patch from the 25th Division, the larger Army unit to which the 161st was attached for much of its campaigns in the South Pacific. He also has a rare copy of a book of sketches of the division’s battles in the Philippines, which was self-published by one of McGrath’s fellow soldiers, William Rutherfoord.

In the front of the book, decades ago, someone glued a small one-paragraph news clipping that reported John McGrath received a Silver Star for carrying a wounded comrade 80 yards to safety.

Tony McGrath said he was glad to have one more small piece of family history.

Discovered by seaman

The dog tag was discovered on Kokorana Island by Edward Bakale, a resident of a much bigger nearby island, Rendova. Last fall, Bakale gave that tag and another he’d found to Elliott, a merchant seaman who was there researching the military campaigns in the Solomon Islands, a chain north of Australia and east of New Guinea where some of the fiercest fighting in the Pacific took place.

How McGrath lost the tag is unknown. Of the 17 dog tags Elliott was given during his trip to the Solomons, seven were from soldiers killed in action. The rest, like McGrath, returned home.

One of Elliott’s goals is to return the tags to the soldiers or family members. From the tag, he knew McGrath originally signed up in the National Guard because his service number started with 20- , and his next of kin was listed as Claude McGrath, on West Augusta Avenue in Spokane.

But Elliot is at sea much of the time, and his window to locate family members was limited. He tried several phone numbers for McGraths in Spokane. None thought they were closely related to a John McGrath.

Then he stumbled across a Spokesman-Review story from March about the search for relatives of another Spokane soldier from the 161st who lost his dog tag when he was killed on Guadalcanal in 1943. He called the newspaper for help finding McGrath’s relatives.

Grew up in north Spokane

Newspaper archives showed John died in 1986. Tony, the youngest son of John and Helen McGrath, is among their children still in the Spokane area and was able to add to information gleaned from old news clips and state archives with the bits he gleaned from his father.

John McGrath grew up in north Spokane in a house on East Liberty Avenue, the youngest son of Thomas and Rose McGrath, who were married in 1901. Claude McGrath, whom John listed as his next of kin, was his oldest brother. He was also a well-known Spokane-area athlete who became Gonzaga University’s athletic director in the 1930s. Tony McGrath said his father had hoped to become a lawyer but left Gonzaga to join the Army.

He was a member of the 161st Regiment in fall 1940 when the unit was put on active duty and sent to Fort Lewis, Wash., for training. The 161st was headed to California the following December when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor; the unit was sent to Hawaii in early 1942, to Guadalcanal at the beginning of 1943 for its first combat, then to Rendova and New Georgia islands that summer. In 1945 they fought in the battle for Luzon in the Philippines.

His father didn’t talk much about the war, Tony McGrath said. He did say he promised his mother not to kill anyone, but then he was bayoneted during his first exposure to combat and “everything changed after that.” Tony McGrath said his father carried a wounded commanding officer back to camp, but the man died en route. It’s not clear whether that’s the action that earned him the Silver Star. Tony McGrath also said his father was discharged for hitting an officer, although he did receive an honorable discharge.

He returned to Spokane, went to work for the Postal Service and was a mailman in north Spokane for many years. When he married Helen Galvin in 1969, he had five children from his first marriage, and she had six from hers. They had one more, Tony.

After John retired from the Postal Service and he, Helen and Tony moved several times, to Boston and to Oregon. “But we always came back to Spokane … to be near family, I think.”

They were in Spokane in 1986 when John was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He’d already had one operation for the disease, which he told Tony was more painful than anything he’d experienced in the war. He opted not to have another one, and he died that December.

After The Spokesman-Review helped trace the connection between John and Tony McGrath, Elliott mailed the dog tag to Spokane with some information on how to read the different lines, and some maps of the island chain where they were found and a brief note about the fighting there. “As a former Marine and current merchant marine, I would like to extend my thanks to your family for your father’s service to our country,” Elliott wrote.