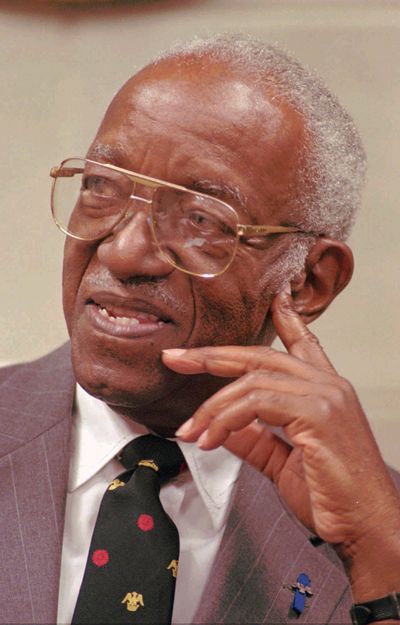

Civil rights scholar Franklin dies at 94

Historian provided inspiration for generation of scholars

WASHINGTON – John Hope Franklin, one of the most prolific and well-respected chroniclers of America’s torturous racial odyssey, died of congestive heart failure Wednesday in a Durham, N.C., hospital. He was 94.

It was more than Franklin’s voluminous writings that cemented his reputation among academics, politicians and civil rights figures as an inestimable historian. It was the reality that Franklin, himself a black man, had seen racial horrors up close and thus was able to give his academic work a stinging ballast. Franklin was a young boy when his family lost everything in the Tulsa race riot of 1921. The violence was precipitated by reports that a black youth assaulted a white teenage girl in a downtown elevator. In the end, more than 40 people died, mostly blacks, although some reports put the death total much higher.

Franklin was among the first black scholars to earn prominent posts at America’s top – and predominantly white – universities. His research and his personal success helped pave the way both for other blacks and for the field of black studies, which began to blossom on American campuses in the ’60s.

In time, a second generation of eminent black scholars – Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates Jr., Georgetown’s Michael Eric Dyson and Princeton’s Cornel West – would follow Franklin to the heights of America’s most illustrious schools.

“He gave us a common language,” Gates, director of the W.E.B. DuBois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard, said Wednesday. “As the author of a seminal textbook, ‘From Slavery to Freedom,’ Franklin gave us young black scholars a common language to speak to each other. He had invented a genre out of whole cloth.”

Gates, a former recipient of a MacArthur “genius grant,” for years was curious as to who had recommended him. He attended a dinner once with Franklin, and Franklin confided that he had been the one to recommend Gates. “And I cried at the table we were sitting at. A lot of us called John Hope ‘the Prince.’ He had such a regal bearing. We’re all the children of John Hope.”

Over the course of his career, Franklin taught at Duke, Harvard and the University of Chicago, and would regale friends with the joy he had teaching at Cambridge University in England. Among his many honors was the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which President Bill Clinton bestowed upon him in 1995.

Franklin’s life became so celebrated in his later years, and his testimony at congressional hearings so frequent, that he seemed almost a fictional figure, a combination of Booker T. Washington and Mark Twain. “I could not have avoided being a social activist even if I had wanted to,” Franklin once said.

Among Franklin’s more popular works, many of which remain constants on college reading lists, are “From Slavery to Freedom” (with Alfred Moss Jr.), “The Emancipation Proclamation,” “Reconstruction After the Civil War,” “A Southern Odyssey: Travelers in the Antebellum North” and “The Militant South, 1800-1861.”