On the Dinosaur Trail

Digs continue to unearth Montana’s prehistoric past

An hour northwest of Great Falls, Mont., rests one of the most important discoveries in paleontology.

It was 1978 and Marion Brandvold was walking through the rolling hills of Bynum, Mont. The nearly rainless area was — and still is— punctuated with prickly pear cactus, and inhabited by deer, elk and a few hardy ranchers.

Brandvold found tiny dinosaur bones at a knoll near Choteau, and changed the face of modern paleontology.

The bones rested on the rock shop owner’s coffee table until local dinosaur expert Jack Horner identified them as juvenile Maiasaurus, a large plant-eating animal that roamed the continent more than 60 million years ago.

Her discovery and Horner’s subsequent digs uncovered a nest of fossilized dinosaur eggs, hatchlings, and the first complete embryonic dinosaur skeleton ever found at what’s now called Egg Mountain, about 15 miles north of Choteau.

What’s important about Egg Mountain is that it undermined the generally accepted theory that dinos were cold-blooded creatures lacking social skills. Nests indicated that Maiasaurus cared for their young and lived in herds, and helped launch a paleo-mania that continues today across Montana.

Even though Egg Mountain is closed to the public to preserve delicate fossils, 15 Montana museums offer collections and public dig opportunities. From Rudyard to Chinook, Malta, Jordan and Fort Peck, Bozeman and Ekalaka, dinosaur field stations, interpretive centers and museums explore an era between 65 and 230 million years ago when inland seas and temperate weather was the norm.

These museums together comprise the Montana Dinosaur Trail, 15 locations of paleontological treasures from one-of-a-kind specimens, like “Leonardo” the mummy Brachylophosaur, to actually learning how to dig for fossils.

The Two-Medicine Center in Bynum hosts the first baby dinosaur bones found in North America, as well as the Guinness Book of World Records’ largest, scientifically accurate dinosaur reconstruction - Seismosaurus halli (earth-shaker lizard). The center offers public, hands-on dinosaur research and education programs ranging from 3 hours to 10 days.

“For a summer vacation, I checked out the Time Scale Adventures site and discovered a variety of programs and that they allowed children under 16 on dig sites (if accompanied by parent),” said Ellen Oaks of Superior, Wisc., who with her middle-school son, Jeremy, have spent two summer vacations in Bynum.

“I had made arrangements for a two-day program at the center,” says Oaks. “The first day we learned about the local geology of the Two Medicine Formation, history of local paleontology, local discoveries, and the best part of all – time at a ‘learning’ site where we learned how to identify what fossil bones looked like.”

They also visited two learning sites.

“At the first site there were hadrasaur bones and at the second there were fossilized hadrasaur egg shells that were small, black, and about a quarter-inch thick,” Oaks said.

Time Scale is a non-profit research and educational center where amateurs have discovered 90 percent of the approximately 1,500 dinosaur bones excavated—nine different dinosaurs to date. Operator David Trexler is an expert at fossil collection and preservation.

It’s here that dinosaur aficionados and grandparents like Marianne Bakker-Rabdau of Spokane find bones and education.

“I have five grandkids,” says retired nurse Bakker-Rabdau. “They all came to visit for three or four summer weeks—without parents. All the grandkids were at the interested age of ‘dinosaur mania.’”

She and husband Dr. Cornelis Bakker took a kid-friendly short course from Time Scale, which Marion Brandvold’s son leads near Egg Mountain.

“The kids were entranced,” Bakker-Rabdau says. “Up to that time, the only dinosaurs I’d ever seen were in movies. It was a very scientific operation—not frivolous in any way. We had such a good time that we’ve taken a 10-day certification course.”

The 10-day program at Quarry—TA.1997.002, also known as Kahn’s Cache, was worthwhile since they now know the proper care of ancient bones.

“My husband helped prepare displays. Each grandkid had a different job, finding bones, applying plaster casts, having a great old time,” she said.

Ice picks, paintbrushes and dustpans line their toolbox. Excavators work on their knees, in grid sections, gently picking rock away from bone, and sweeping excess into a bucket to be dumped onto a tailing pile. When large pieces are revealed, the crew jackets the skeleton in a plaster casing.

Bakker-Rabdau said some might find it tedious, “like beachcombing, but for me, it’s quite freeing. Every day, we sit on the dirt in the rolling hills, getting dirty and dusty.”

They find bones, like ones she describes as Hadrasaurs, the duck-billed dinosaurs, “bones with teeth bites. It was a baby bone with teeth marks in it.”

People have been finding bones in Montana for more than a century. The first find modern find occurred in 1854 at the mouth of the Judith River, about 40 miles north of Lewistown.

Geologist Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden explored what was at the time Nebraska Territory. His first find was a collection of teeth, bones and shells from near the river’s mouth, the first dinosaur discovery in the Western Hemisphere.

Today, the Montana Dinosaur Trail’s other sites offer a remarkable variety in species displays and educational opportunities. For example, the Earl Clack Museum in Havre, just acquired a baby Maiasaura cast to accompany displays of 75 million year old dinosaur eggs and embryos found in area, called the Judith River Formation. The eggs were laid by a Lambeosaur along the banks of an ancient river and estuary of the Bearpaw Sea that once covered this area.

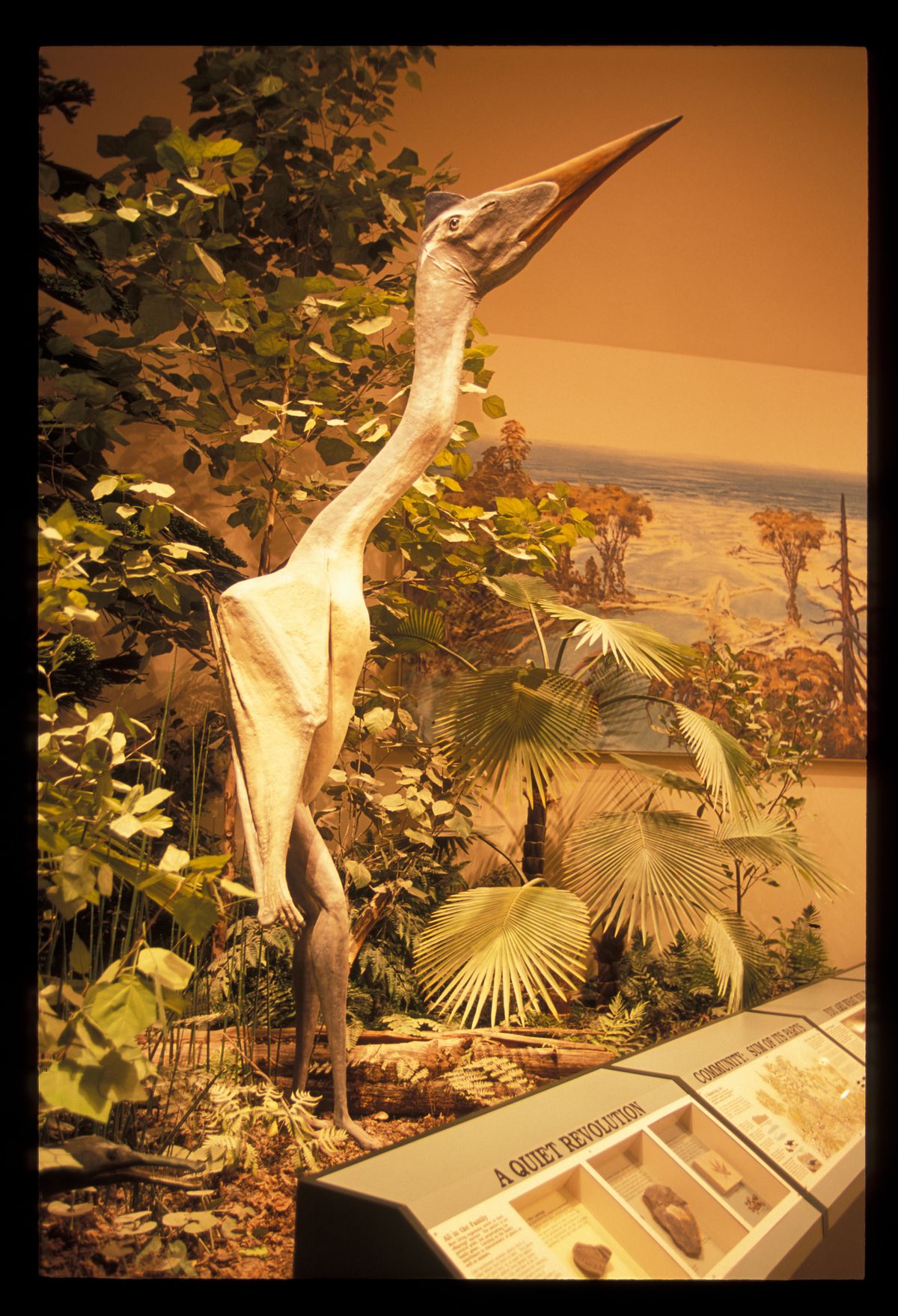

Most celebrated is Bozeman’s Museum of the Rockies at Montana State University and its $4 million Hall of Giants. It includes a deinonychus scaling the back and neck of a plant eater sauropod. The 11-feet long deinonychus had sharp talons plus 60 curved teeth.

Other exhibits display real horns and teeth under glass, and replicas where it’s OK to touch. Kid-magnet touch screens allow the user to “build” a dinosaur or electronically “visit” a dig site.

Eastward is a land of golden mushroom-shaped hoodoos at Makoshika State Park and the Glendive Makoshika Dinosaur Museum, where the Hell Creek Formation unleashed 10 species from mud and sandstone.

A complete Triceratops horridus skull is at the visitor center. A popular hoodoo hike on the Diane Gabriel Trail reveals dinosaur bones in the sandstone where hikers ascend the brief 1.5-mile loop trail to an overview of the park’s 11,634 acres of hoodoo, pine and juniper.

There are other fantastical glimpses into the Paleozoic past such as the southeastern Montana town, Ekalaka and Carter County Museum’s Anatotitan copei, one of only five know Anatotitan skeletons in the world. This large duckbilled dinosaur weighed about 3.5 tons, slightly larger than the Maiasaura, and ran in herds during the late Cretaceous Period.

At the Old Trail Museum, the local mud and sandstone of the Two Medicine Formation preserved Maiasaura and her lovely eggs. There’s a Sauronitholestes skeleton cast of the hollow-boned raptor meat-eating bird robber, named because the carnivore resembles modern birds.

Brachylophosaurus Canadenis, Albertasaurus and Tyrannosaurus Rex and their museums are part of the Montana Dinosaur Trail, designated as an official state route in 2005 in conjunction with the grand opening of the Fort Peck Interpretive Center.

Maps, Dinosaur Trail facilities and dinosaur experts are members of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, which prohibits the illegal collection and sale of paleontological resources.

Some private landowners allow fossil collection with permission, but researchers discourage legal private digs because all remnants of dinosaurs remain important to the scientific world— even now, new discoveries reveal global connections.

For details about the Montana Dinosaur Trail, visit www.mtdinotrail.org and learn about The Prehistoric Passport, which describes the displays, exhibits and activities at each of the trail’s 15 facilities in 12 communities.