Mind games

Toymakers tap into the human brain to challenge gameplayers to a contest of mind over matter

You slip the wireless headset on. It looks like something a telemarketer would wear, except the earpieces are actually sensors, and what looks like a microphone is a brain wave detector. You place its tip against your forehead, above your left eyebrow.

A few feet away is a ping-pong ball in a clear tube called the Force Trainer. The idea is to use your thoughts alone, as recognized by the wand on your forehead, to lift the ball.

Your brain’s electrical activity is translated into a signal understood by a little computer that controls a fan that blows the ball up the tube. Levitates it. As if by magic. It’s mind over matter.

All you have to do is concentrate. On anything, it doesn’t matter. The harder you concentrate, the higher the ball goes. A musician says he played a song in his head and focused on a particular chord change. A former high school tennis star focused on his 120 mph serve. One woman brought the image of a candle flame to mind. The ball rose.

Concentrate. Concentrate.

A sound erupts – first a groan, then a woooo, WOOOO, like a Halloween ghost.

The ball spins, slowly at first, then faster.

Concentrate, concentrate.

And then the ball rises inside the tube. Up it lifts, two inches, four inches – a foot!

You giggle and your concentration is broken; the ghostly sound fades and the ball drops back into its nest with a gurgle.

You have just controlled a physical object with your mind.

Competing mind-over-matter toys from Mattel and Uncle Milton Industries are coming this fall to a store near you. They are the first “brain-computer interfaces” to enter the consumer mainstream.

Toys, but so much more. They embody a dream of the ages: controlling the world with your thoughts. Telekinesis. The stuff of the gods.

•

The question everyone has about these gizmos is whether they are parlor tricks like Magic 8 Balls or Ouija boards. Even Geoff Walker, a senior vice president at Mattel, acknowledges that users “spend the first 20 minutes stunned that it actually works.”

Evidence in favor of them being for real is that some people are worse than others at controlling them – certainly not a marketing feature.

Lawyers and other multitaskers, for example, tend to have a terrible time focusing their brain waves, says Johnny Liu, of NeuroSky, the creator of the mind-over-matter headset. But there are those to whom controlling the device comes effortlessly and instantly, as if single-mindedness is the person’s natural default position.

What happens when millions of youngsters in a notoriously ADHD generation start getting programmed by these new toys? What happens when they start being rewarded for very long periods of intense concentration?

Nobody in the toy industry seems to know. But it sure looks like parents are about to find out.

Likely Christmas competitors, Mattel’s $80 Mindflex and Uncle Milton’s $130 Force Trainer both involve levitating a ping-pong-like ball.

Mattel is aiming Mindflex at 8- to 12-year-olds, both girls and boys, although “it seems like a product that can inspire a ‘wow’ from 8 to 82,” says Walker.

Uncle Milton is aiming the Force Trainer, which has a “Star Wars” theme, at those adults who still can’t get too much Luke Skywalker in their lives, and then at boys 6 to 11.

Reyne Rice, the toy trends specialist for the Toy Industry Association, sees great potential for games. Imagine a “CSI”-like law-and-order game that could use a lie detector. Or multiplayer games.

“Whoever has the strongest mind control can take over the thing on the screen,” Rice says.

•

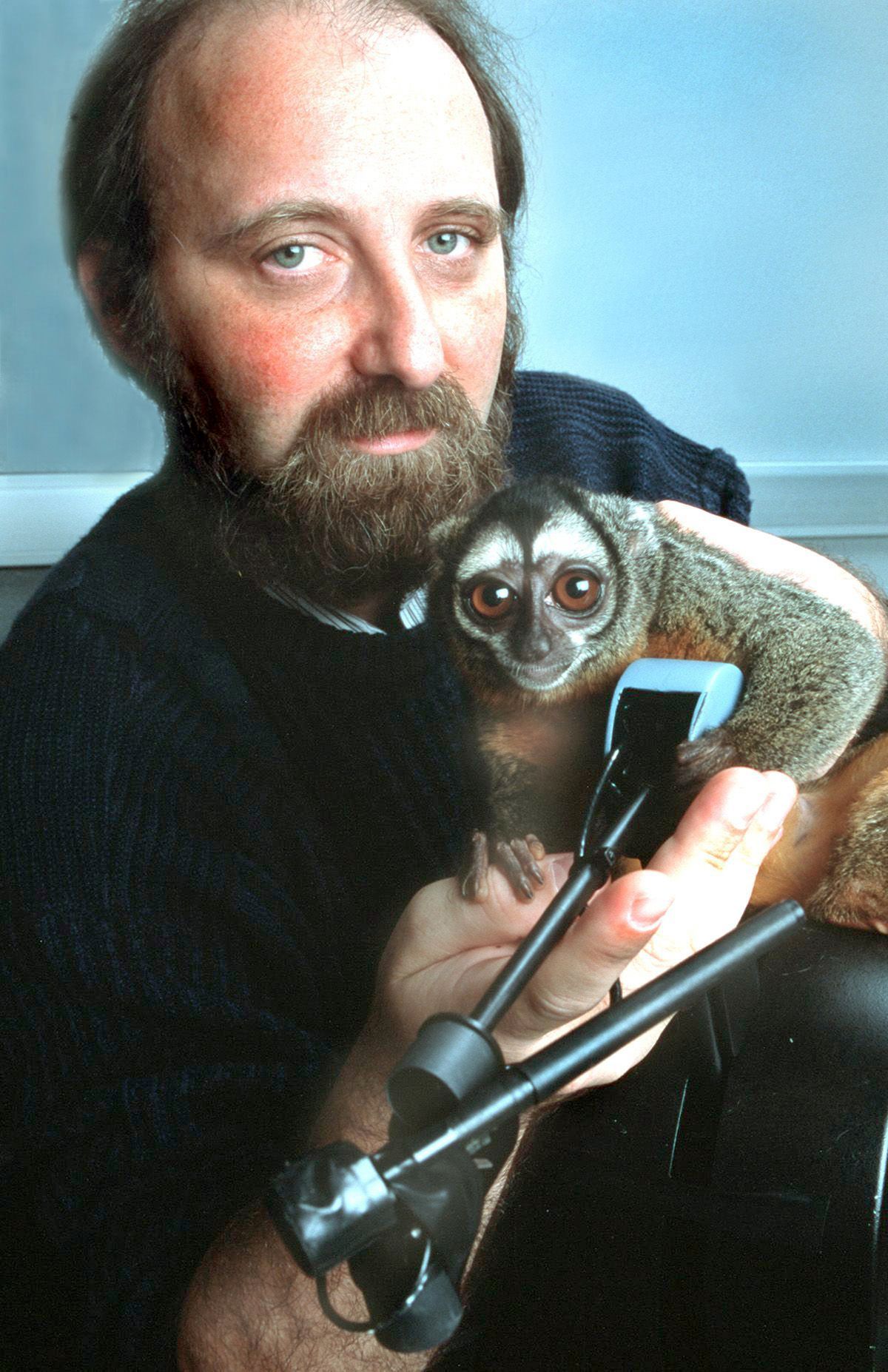

Nine years ago, scientists created the world’s first telekinetic monkey. Belle, a cute little owl monkey in the lab of Miguel Nicolelis at Duke University, was the first to control tangible objects, long distance, with her thoughts.

How do you make a monkey telekinetic?

First you get her into a computer game. She knows that if a light suddenly shines on her screen and she moves her joystick left or right to hit it, she gets a drop of juice.

Then the researchers drill a hole in her head. They take a device the size of a baby aspirin, out of which come many superfine wires, and lower it into Belle’s motor cortex – the portion of the brain that plans muscle movement. The object is to line up each wire with an individual neuron to detect its firing.

Then comes the big moment in telekinesis.

When Belle resumes her game, the scientists put the signal from her brain on the Internet and pipe it 600 miles north to a robotic arm at MIT. Sure enough, it starts dancing like a ballerina in exactly the same fashion as Belle’s arm, “choreographed by the electrical impulses sparking in Belle’s mind,” her researchers report.

“Amid the loud celebration that erupted in Durham, N.C., and Cambridge, we could not help thinking that this was only the beginning of a promising journey,” Nicolelis wrote in Scientific American.

Indeed, work is advancing rapidly. Four profoundly paralyzed humans equipped with a “BrainGate” implant created by the biotech firm Cyberkinetics have demonstrated their ability, with just their thoughts, to check and send e-mail; turn televisions, lights and appliances on and off; and control a wheelchair.

Monkeys equipped with brain-controlled artificial arms have learned how to guide food to their mouths. A monkey in Nicolelis’ lab recently controlled a humanoid robot in Japan.

But the most spectacular work has centered on neural control of mechanical arms, hands and legs. The goal of a program funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is to soon produce intelligent artificial limbs controlled by your nervous system that will allow you to pitch a fastball, thread a needle or play a piano.

“You have to dream big,” says Col. Geoffrey Ling, a neurologist and program manager. “If you don’t dream that you’re going to the moon, you won’t go to the moon.”

•

As a mind-reading location, your forehead has only one significant advantage.

“It’s a horrible place to get signals. But that’s the only place most people do not have hair,” says Stanley Yang, chief executive of NeuroSky. “Hair is not conductive.”

NeuroSky, which has its sights set on providing brain-wave sensors for the automotive, health-care and education industries, is in the forefront of turning brain-computer interfaces into cheap, ubiquitous consumer items.

The prospect for mind-controlling matter dates to 1875, when Richard Caton discovered that you could peer into the workings of the brain by detecting its electrical impulses.

In 1929 came the first electroencephalograph – the EEG machine – that became the staple of science-fiction movies. But hospital EEG machines are expensive, enormous and not good at fine control; plus you have to smear conductive goop on your head.

Thus, NeuroSky’s adaptation is no small thing. They get a single dry sensor to read your bare forehead – no goop, no holes drilled through the skull. They get the device to focus on the correct signals from that extremely noisy brain area, filtering out everything else; that’s their big trick.

“It’s like being at a crowded party, and picking out one quiet conversation,” says Liu.

Then they make it small, light and cheap, and deliver it to market.

“The sensors you are seeing today are first generation,” says Yang. “You have to wear it. The second generation can sense your brain waves and other bio-signals from a distance. Like sensors in your car seats that can go through clothes without touching you.

“Embed the sensor in the seat belt. In the steering wheel. Or embed a sensor in the headrest.”

Yang wants the car to know if you are falling asleep. Or drunk. Or wishing the air conditioning would go on, or the music would play more softly.

Where we go from there is limited only by imagination: brain-controlled television remote controls, video games, race cars.

Steve Koenig, director of industry analysis at the Consumer Electronics Association, sees the opportunities for military robot wrangling, say, or mastering space or undersea exploration, or allowing the profoundly ill or disabled to control their surroundings.

He is, however, a skeptic about how eagerly we will embrace the toys. As for the TV remote control, Koenig says: “If, to control things, you have to concentrate, at what point is it much easier to just grab the knob and turn the volume down?”