Senate passes measure for credit card reform

Card companies warn of higher fees for all customers

WASHINGTON – Landmark credit card legislation, poised to reach President Obama’s desk as early as Memorial Day, will force the card industry to reinvent itself and consumers to rethink the way they use plastic.

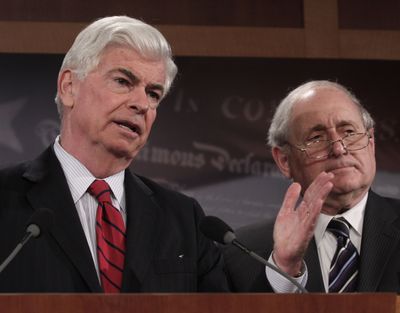

The Senate Tuesday took a critical step forward by voting 90 to 5 to pass a bill that would sharply curtail credit card issuers’ ability to raise interest rates and charge fees. Lawmakers will now turn to reconciling differences with a similar bill approved by the House last month. Swift passage was expected given that the Senate version received so much bipartisan support and that the White House has pressed for action.

When Obama signs a bill into law as expected, the $960 billion credit card industry will go through restructuring that could have broad implications for consumers.

The bill will prohibit card companies from raising interest rates on existing balances unless the borrower is at least 60 days late. If the cardholder pays on time for the following six months, the company would have to restore the original rate. On cards with more than one interest rate, issuers will have to apply payments first to the debts with the highest rates, which would help borrowers pay off their cards more quickly.

Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner said the bill “will help create a more fair, transparent and simple consumer credit market.”

Card executives said the changes will force them to charge higher rates and annual fees to delinquent customers and those in good standing.

“This bill fundamentally changes the entire business model of credit cards by restricting the ability to price credit for risk,” said Edward Yingling, the chief executive of the American Bankers Association. He said that lending would become more risky and that, “It is a fundamental rule of lending that an increase in risk means that less credit will be available and that the credit that is available will often have a higher interest rate.”

Scott Talbott, senior vice president of government affairs for the Financial Services Roundtable, an industry group, said available credit could be reduced by as much as $2 billion. Those with the weakest credit histories would be hardest hit.

When credit cards were introduced about 50 years ago, issuers practiced a one-size-fits-all approach of charging an annual fee and roughly the same interest rate of about 18 percent to everyone. As the industry became more deregulated in the 1980s, around the time that credit scores were introduced, issuers were able to separate the risky from the not-so-risky borrower and tailor the terms of card contracts.

The money they made from customers who did not pay their bills in full each month became an important revenue source.

The industry makes $15 billion annually from penalty fees, and one-fifth of consumers carrying credit card debt pay an interest rate above 20 percent, according to figures cited by the White House and compiled from the Government Accountability Office and the Federal Reserve.

To make up for the lost revenue, card issuers will turn to those customers who pay what they owe in full and on time every month, analysts said.

Gone will be the days when creditworthy customers enjoyed the benefits of low interest rates and cards that offer rewards such as frequent flyer miles and cash back, they said. Annual fees, which had been banished to cards with rewards programs, are likely to return. Offers for zero percent balance transfers are likely to become rarer.

“This industry will start looking more like a one-size-fits-all pricing approach which dominated in the ’80s – 18 percent interest and … $20 annual fees,” said David Robertson, publisher of the Nilson Report, which covers the industry. Customers who pay in full each month will have “to start picking up the slack, to start pulling their weight.”

Consumer advocates and legislators pointed out that the legislation still allows issuers to raise interest rates on future balances.

It also does not set any interest rate caps, allowing issuers to charge new customers any rate they want.

“This ominous we’re-going-back-in-time threat doesn’t make a whole lot of sense,” said Travis Plunkett, legislative affairs director at the Consumer Federation of America.