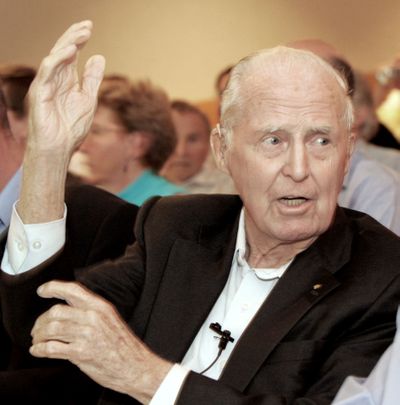

Nobelist Borlaug, 95, dies

‘Man Who Fed the World’ said to have saved 1 billion

DALLAS – Scientist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Norman Borlaug rose from his childhood on an Iowa farm to develop a type of wheat that helped feed the world, fostering a movement that is credited with saving up to 1 billion people from starvation.

Borlaug, 95, died Saturday from complications of cancer at his Dallas home, said Kathleen Phillips, a spokesman for Texas A&M University where Borlaug was a distinguished professor.

“Norman E. Borlaug saved more lives than any man in human history,” said Josette Sheeran, executive director of the U.N. World Food Program. “His heart was as big as his brilliant mind, but it was his passion and compassion that moved the world.”

He was known as the father of the “green revolution,” which transformed agriculture through high-yield crop varieties and other innovations, helping to more than double world food production between 1960 and 1990. Many experts credit the green revolution with averting global famine during the second half of the 20th century and saving perhaps 1 billion lives.

“He has probably done more and is known by fewer people than anybody that has done that much,” said Dr. Ed Runge, retired head of Texas A&M University’s Department of Soil and Crop Sciences and a close friend who persuaded Borlaug to teach at the school. “He made the world a better place – a much better place.”

Borlaug began the work that led to his Nobel in Mexico at the end of World War II. There he developed disease-resistant varieties of wheat that produced much more grain than traditional strains.

He and others later took those varieties and similarly improved strains of rice and corn to Asia, the Middle East, South America and Africa. In Pakistan and India, two of the nations that benefited most from the new crop varieties, grain yields more than quadrupled.

His successes in the 1960s came just as experts warned that mass starvation was inevitable as the world’s population boomed.

“More than any other single person of his age, he has helped to provide bread for a hungry world,” Nobel Peace Prize committee chairman Aase Lionaes said in presenting the award to Borlaug in 1970. “We have made this choice in the hope that providing bread will also give the world peace.”

But Borlaug and the Green Revolution were also criticized in later decades for promoting practices that used fertilizer and pesticides, and focusing on a few high-yield crops that benefited large landowners.

Borlaug often said wheat was only a vehicle for his real interest, which was to improve people’s lives.

“We must recognize the fact that adequate food is only the first requisite for life,” he said in his Nobel acceptance speech. “For a decent and humane life we must also provide an opportunity for good education, remunerative employment, comfortable housing, good clothing and effective and compassionate medical care.”

Borlaug also pressed governments for farmer-friendly economic policies and improved infrastructure to make markets accessible. A 2006 book about Borlaug is titled “The Man Who Fed the World.”

He remained active well into his 90s, campaigning for the use of biotechnology to fight hunger. He also helped found and served as president of the Sasakawa Africa Foundation, an organization funded by Japanese billionaire Ryoichi Sasakawa to introduce the green revolution to sub-Saharan Africa.

In 1986, Borlaug established the Des Moines, Iowa-based World Food Prize, a $250,000 award given each year to a person whose work improves the world’s food supply.

He received the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor given by Congress, in 2007.