New global climate pact possible, but with wrinkle

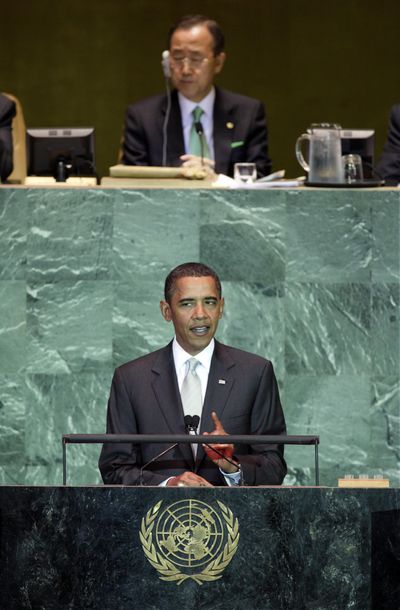

Several world leaders Tuesday gave the most decisive indication in months that they would work to revive floundering negotiations aimed at securing a new international climate pact. But the vision President Barack Obama and others outlined at the United Nations’ climate summit in New York – in which countries offered a series of individual commitments – suggests a potential deal may look much different from what its backers originally envisioned.

Initially many climate activists had hoped this year would yield a pact in which nations would agree to cut their greenhouse gas emissions under the auspices of a legal international treaty. But now recent announcements by China, Japan and other nations point to a different outcome when U.N. climate talks get under way in Copenhagen in December: a political deal that would establish global federalism on climate policy, with each nation pledging to take steps domestically.

“Many of the jigsaw pieces of an agreement lie across the board, but we have to put them together,” said British Energy and Climate Change Secretary Edward Miliband, adding that negotiators are looking for a solution where “every country is satisfied that every country is taking action” on climate change.

The world’s biggest carbon emitters took pains Tuesday to highlight what they had already done to curb their footprint, and what they would do in the future. Obama recounted how his administration had made major investments in clean energy, set new fuel economy standards for vehicles and pressed for House passage of bill to cap emissions and allow companies to trade pollution permits.

“We understand the gravity of the climate threat,” Obama said. “We are determined to act. And we will meet our responsibility to future generations.”

Less than an hour after he spoke, the Environmental Protection Agency announced it had finalized rules requiring facilities that emit the equivalent of 25,000 metric tons of carbon or more annually to report their pollution to the agency each year.

Chinese President Hu Jintao, for his part, said his country would establish “mandatory national targets” for the reduction of emission-intense energy sources, and said it would increase the size of the nation’s forests. The Chinese leader said his country would place climate change at the center of its long range plans for economic and social development, and vowed to “endeavor to cut carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP by a notable margin by 2020 from the 2005 level.”

Julian Wong, a senior fellow at the liberal Center for American Progress, said Hu’s proposal “is clearest signal yet that China is willing to take on responsibilities that are commensurate with its resources and global emissions impact.”

Japan’s Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama renewed his pledge to reduce his country’s emissions by 25 percent by 2020, the most ambitious commitment to curbing greenhouse gases by developing nations. But Japan’s commitment, he said, would have to be conditioned on the willingness of other industrial powers to sign on to similar commitments.

“I am resolved to exercise the political will required to deliver on this promise by mobilizing all available policy tools,” he said. “However, Japan’s efforts alone cannot halt climate change, even if it sets an ambitious reduction target.”

Several leaders of other nations – rich and poor alike – tried to ratchet up the political pressure for more ambitious greenhouse gas reductions. The U.N. offered the Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed a prime speaking spot after Obama: Nasheed sounded weary at the prospect of playing the role of climate change’s poster boy for disaster for yet another year.

“On cue, we stand here and tell you just how bad things are, we warn you that unless you act quickly and decisively, our homelands and others like will disappear beneath the rising sea before the end of the century,” he said. “In response, the assembled leaders of the world stand up, one by one, and rail against the injustice of it all … But then, once the rhetoric has settled and the delegates have drifted away, the sympathy fades, and the indignation cools, and the world carries on as before.”

French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who has been working behind the scenes to craft a joint negotiating climate position with Brazil for Copenhagen, called on industrial leaders to hold a summit in mid-November to increase pressure on countries to strike a deal by December. “The time has passed for diplomatic tinkering, for narrow bargaining,” he said. “The time has come for courage, mobilization and collective ambition.”

“That’s the real power of the U.N.,” said Ned Helme, president of the Center for Clean Air Policy. “It’s all about the view of everyone. Youstand up and say what you’re going to do.”

U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, who organized the session, prodded governments to look beyond their own national interests and make painful compromises to guarantee a climate deal by the end of the year. “Climate change is the pre-eminent geopolitical and economic issue of the 21st century,” he said. “It will increase pressure on water, food and land, reverse years of development gains and exacerbate poverty, destabilize fragile states and topple governments.”

While Obama told the assembly the world must come up with a “flexible and pragmatic” solution to global warming, Republicans immediately criticized him for trying to impose a mandatory cap on carbon emissions.

“I believe very strongly that action on climate change has to include meaningful reductions,” Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, said in a call with reporters. “We have also got to make sure that we don’t kick the economy in the head.”