Money is major roadblock for final leg of freeway

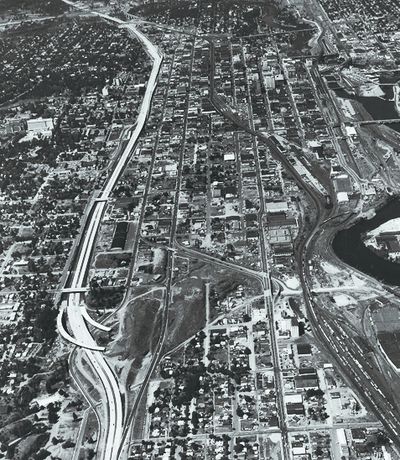

Exit 282 of Interstate 90 sits as a monument to the stops and starts of building a north Spokane freeway.

Engineers designed the massive Hamilton ramps to be the start of a new thoroughfare through Spokane. The exit opened in 1971 but never got connected to a freeway.

The proposed path along Hamilton Street fell victim to neighborhood opposition; the state finally dismissed it as a possible highway in 1991. By then, a new route through railroad property in Hillyard was gaining favor. It won federal approval in 1997.

Local leaders say they’re determined not to let the housing lots left vacant from state preparations over the past year in East Central become another symbol of an abandoned freeway route. But even with the first half of the freeway – north of Francis – scheduled to be fully open by the end of 2011, major obstacles remain: money and politics.

Construction to finish the freeway is estimated to cost $1.6 billion.

State Sen. Chris Marr, D-Spokane, said he’s optimistic about the completion of the North Spokane Corridor, largely because county, city and state leaders agree that diverting trucks from city streets is a priority. He said the opening of the freeway from U.S. Highway 395 at Wandermere almost to Francis next year, as well as the demolition of East Central homes, will give the project momentum.

Marr said opposition to the corridor is less significant than what’s faced by other major projects in the state. That could help attract state or federal support, he said.

“The city of Spokane cannot afford to maintain streets to be used as highways,” Marr said.

State Senate Majority Leader Lisa Brown, D-Spokane, said money to pay for the construction of the next phase – from Francis almost to the Spokane River – could come from a gas tax on the statewide ballot in the next few years. A similar gas tax has paid for much of the work north of Francis.

The state has spent $38 million to buy land and for engineering through Hillyard to the river. That will make the project “shovel ready,” Marr said.

The most expensive portion – crossing the river and connecting the corridor to I-90 on a bridge and viaduct – may require local matching funds, Marr said.

City and county leaders are considering new taxes or fees to help pay for the corridor. One idea is a new vehicle license tab fee that would be used mostly for maintenance of local streets. But a certain percentage could be diverted for “projects of regional significance” – such as the north Spokane freeway.

City Councilwoman Nancy McLaughlin said she’s skeptical of the need to raise local taxes or fees for the project, but she won’t rule it out.

“If there’s no other option than coming up with a match, we’re going to have to put our heads together and figure out how to do that, because we have to get this project done,” she said.

McLaughlin said a tab fee should only be considered if voters have a say. County commissioners could approve a tab fee of $20 or less without asking voters.

Republican County Commissioner Todd Mielke said he’s open to a statewide gas tax, but only if the corridor will be a top priority for the money raised.

“We’ve really come together as a community to say we really want to see this thing finished,” Mielke said.

Although some elected and neighborhood leaders say the East Central portion of the freeway should be scaled back, opposition to the freeway has been quiet in recent years.

Even City Councilman Richard Rush, who has raised several concerns about the project, said he has no problems with it if “the state wants to pay for it.”

City officials say that a north Spokane freeway would make Spokane more attractive for businesses.

“We have to be able to put Spokane on the map as a place you can get your goods in and out of here easily, not on city streets,” Mayor Mary Verner said. “That’s a double desire on my part. I don’t want my streets worn out, and I want freight to move quickly through the city rather than idling at every stop sign.”

For decades there’s been debate about the effects of a north Spokane freeway on air pollution. State transportation officials say a freeway would help clear the air by allowing vehicles to move quickly through the city. Opponents argue that the freeway would promote sprawl and that whatever is gained through efficient driving would be lost by a route that encourages people and businesses to travel away from the city center.

This month, Citizens for Sensible Transportation Planning filed a federal lawsuit against the state Department of Transportation.

It says the state should be required to study the freeway’s health effects on nearby residents.

John Covert, president of the group, said people who live along the route should know how it could affect their health.

“I would like to have a robust conversation about, ‘Do we really need it, and what should it look like?’ ”

Freeway supporters say there’s been robust conversation for more than half a century – and it’s time to move ahead.

Verner said she’s reluctantly supportive of the design of the “trumpet,” the massive ramp structure that would connect the new freeway with I-90.

“It’s just gigantic,” she said. “Once we started putting millions of dollars into (it), employing people and moving people out of businesses and out of their homes, it took on a life of its own.”

Rush believes that the highway could be scaled back. He also suggested it should become a toll road, focusing on what many leaders say is its top job: moving freight.

“We know a lot more about transportation and its impacts, its implications and its unintended consequences now,” Rush said. “With the price of oil, there’s a chance it will be obsolete before it’s completed.”

Marr and state transportation leaders said charging to use the freeway wouldn’t work because there are too many alternative northern routes.

State officials stress that the corridor would be used by more than cars and trucks. A bike and pedestrian trail is being constructed alongside it, and the freeway comes with extra land set aside for a possible light rail system.

Brown said with new federal transportation priorities, light rail along the freeway is more than a pipe dream. She added that a new freeway wouldn’t necessarily mean sprawl.

“Land-use decisions can be aligned with it to promote the vitality of urban neighborhoods,” she said.

While officials tout the route’s usefulness to move goods in and out of the city, some commuters also say they’re excited by the freeway’s time-saving possibilities.

Evelyn Dugger lives near Whitworth University and works near Sprague and Freya. If she leaves work at 5 p.m., it takes her about 45 minutes to get home.

“I would hope that it’s done before I die,” Dugger said, noting that the freeway has been talked about since she moved to Spokane in 1966.

“I would love to see it done. It’s time.”