MAC pays tribute to Ruben Trejo

‘Beyond Boundaries’ exhibit opens Saturday

The upcoming Ruben Trejo exhibit at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture is a sweeping celebration of the man and his work – lacking only the presence of the man.

“It’s a very tragic thing that Ruben died last July,” said MAC senior art curator Ben Mitchell. “Many of us are still in mourning. … I was working with him for three years on this. ”

Yet a celebration it is. One of Mitchell’s goals was to demonstrate, once and for all, why Trejo was one of the most influential artists ever to work in the Inland Northwest.

Trejo’s art “prefigures a new American art, grounded in a heterogeneous and diverse society,” writes Stanford University art scholar Tomas Ybarra-Frausto in an essay in the exhibit’s accompanying book.

Saturday’s opening doubles as the book launch for a definitive full-color overview of Trejo’s career, published by the University of Washington Press and the MAC. It’s edited by Mitchell and includes essays by Ybarra-Frausto and writer John Keeble.

Trejo rolled into Cheney in a Volkswagen van in 1973, freshly hired as an art professor at Eastern Washington State College (now University). For the next three decades, he helped build EWU’s art department, mentored Chicano students and produced stunning, evocative and sometimes surreal sculptures, constructions, drawings and woodcarvings.

His works have traveled to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. About 50 will be on display in this exhibit.

“He was known beyond our region,” said Mitchell. “He was involved in all of the big Chicano and Latino shows. But he was an American artist – and he never had this kind of show.”

It’s a show that Trejo would have made a point of attending – if it were for another artist.

“He was an absolute visible presence in the Spokane art community,” said Mitchell. “I don’t think I ever attended an art event in Spokane, at Gonzaga University, at EWU, where he wasn’t there. He was absolutely supportive of other artists.”

He was also intensely supportive of the Chicano students at Eastern. Because of Trejo, the university’s Chicano Education Program exists today.

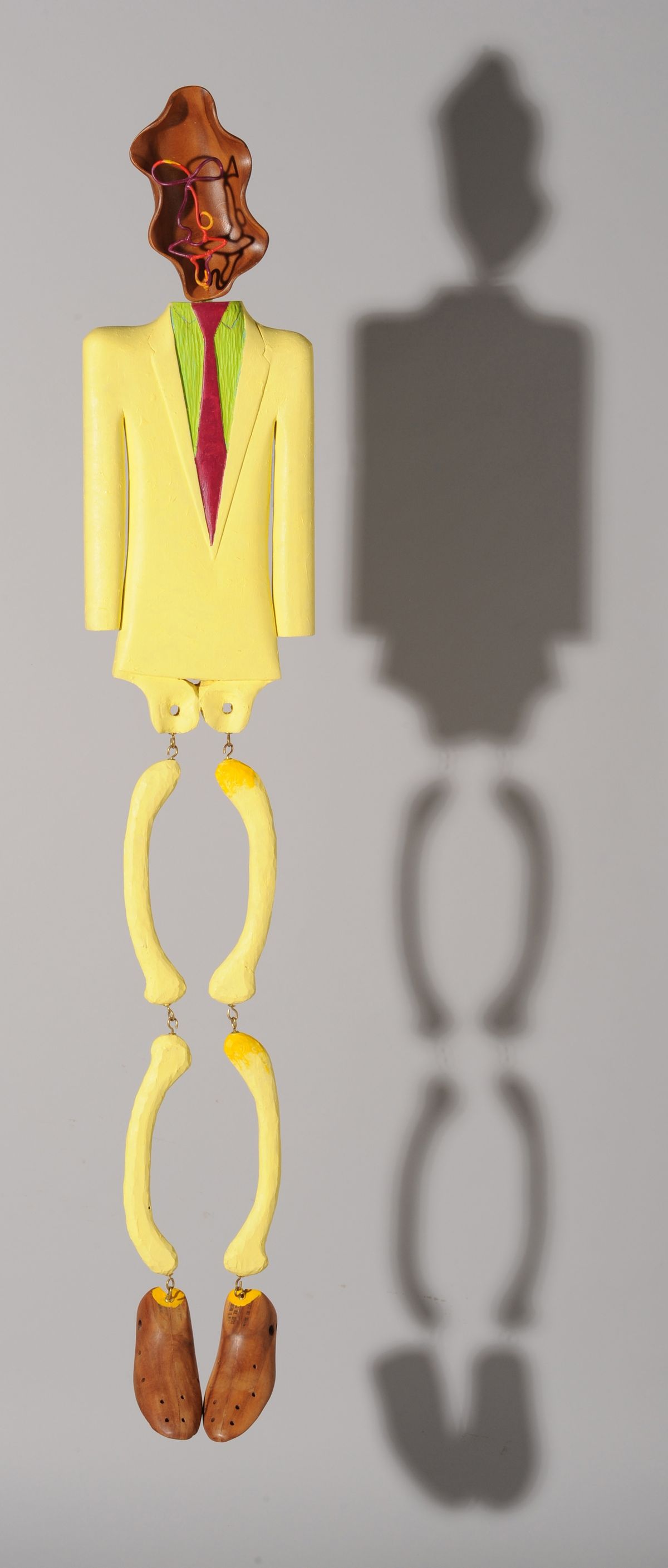

The exhibit shows off Trejo’s amazing versatility – “he was absolutely unafraid of any medium,” said Mitchell. You’ll see brushed aluminum, paper collages, welded constructions, bent railroad spikes and bronze-cast underpants.

Yes, you read that correctly. Trejo’s art often has a sly sense of humor.

In the words of Ybarra-Frausto, his work is “serious enough about life to delight in its representation and frivolous enough to scoff at it.”

The exhibit is rich with Trejo’s favorite themes and motifs, which include:

Chicano identity and “machismo” – This recurring theme is most vividly displayed in a wall sculpture titled “Mucho Macho,” which includes knives (representing macho violence), dried red peppers and bronze-cast underpants – slashed in half.

“What does ‘macho’ get you?” asks Mitchell. “Hurt.”

Pre-Columbian art – Trejo, whose parents were from the Michoacan region of Mexico, often used pre-Columbian stone carvings in his work. An acrylic-and-paper-collage piece titled “El Trio” depicts three figures in suits, topped with ancient carved heads.

Pinocchio – A corner of “El Trio” also includes an image of Pinocchio, complete with growing wooden nose.

It’s a commentary on lying – and possibly about a woodcarver with the hubris to try to create a “real boy.”

Politics and current events – “Chicano Retablo in Honor of J. Edgar Hoover and His Attendant Roy Cohn” features a pink zoot-suited man with a skull for a head.

“A lot of (Trejo’s) work is deeply socially engaged in the time he lived in,” said Mitchell.

Pinocchio also makes a growing-nose appearance in this piece.

Catholicism – The show includes several series of “Nichos” (suggestive of religious displays) and crucifixes, some made with nails.

Railroad spikes – One huge installation is made entirely of dozens of railroad spikes, possibly hearkening back to Trejo’s family background. His father emigrated to St. Paul, Minn., and became a railroad worker. Trejo was born in a converted boxcar used as worker housing.

Growing things – “The Onion Fields” represents one of Trejo’s earliest memories, being taken to a farm field where his godparents worked as seasonal laborers. Yet in his hands the soil is made of brushed aluminum and the windblown onion stalks are stiff silver-and-purple wires. Chilis also show up in many of Trejo’s pieces.

The dizzying variety of themes, genres and ideas is striking. It’s clear that Trejo, up until the very end, couldn’t stop creating.

“It’s as if his making things is akin to breathing the very air,” wrote Keeble about his longtime friend.

So maybe the man himself won’t be present in the room. Yet his presence – that will fill every corner of the exhibit.