Coaches face tight scrutiny

Attitudes different when it comes to discipline

DALLAS – Before Wednesday, few college football historians would have associated coaches Mike Leach and Woody Hayes.

But Texas Tech’s quirky Leach and Ohio State’s combustible Hayes now are forever linked, fired by their schools for, in effect, bullying a player.

Leach’s legion of supporters will say that his alleged closeting of injured Tech receiver Adam James in a “shed” falls well short of Hayes’ punch to the throat of Clemson nose guard Charlie Bauman during the 1978 Gator Bowl.

But Leach’s shocking dismissal and the forced Dec. 3 resignation of Kansas’ Mark Mangino seem to show that administrators, players and players’ parents are far less tolerant of what once were accepted motivational or disciplinary coaching tactics.

“When you ask, ‘Has coaching changed?’ the answer is ‘No, it hasn’t,’ ” said Grant Teaff, executive director of the American Football Coaches Association. “What’s changed is the focus, the magnifying glass, the culture we live in.”

Teaff, who coached Baylor from 1972 to 1992 and is in college football’s hall of fame, made his comments Wednesday morning, two hours before Leach’s firing.

At the time, it was bizarre enough that Leach’s attorney had filed for a temporary restraining order and injunction against Tech that would allow then-suspended Leach to coach in today’s Valero Alamo Bowl.

“I’m kind of mind-boggled over it,” Teaff said. “It’s new territory.

“It’s, as I guess they say on TV, a sign of the times.”

To be sure, the era of legendary disciplinarians such as Paul “Bear” Bryant is long gone.

In 1954, entering his first season as Texas A&M’s coach, Bryant held a 10-day summer training camp in Junction, Texas.

With Bryant weeding supposedly weak players from the strong by prohibiting water breaks in 100-plus-degree heat, the two-to-three dozen players who didn’t quit became known as The Junction Boys in Aggie lore.

If there was a line football coaches weren’t supposed to cross, no one dared voice it in those days.

In ensuing decades, concerned voices have grown louder and the line clearly has moved, particularly in regard to players’ health and safety.

Leach’s alleged confining of James to “small, dark places” on two occasions occurred after he had been diagnosed with a concussion. This season, concussions have become a particular point of concern at all football levels.

During spring training in late March, Leach had demoted wide receiver Edward Britton for failure to regularly attend class and maintain good grades. Leach ordered Britton to study at a desk at midfield in 30-degree weather, albeit in a heavy coat.

“Ed didn’t like showing up and studying at places I felt like he needed to and like the academic people asked him to, so he can go study out there on the 50-yard line,” Leach told the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal that day.

Leach ordered Britton to remain in the cold for 90 minutes after practice, adding:

“If somehow he fails to do that, then that’ll be the last we ever hear of ‘Easy Ed.’ ”

Britton has played in all 12 games this season, catching 32 passes and scoring three touchdowns.

Leach was named Big 12 Coach of the Year in 2008 after leading the Red Raiders to an 11-2 record. Kansas’ Mangino, the 2007 national coach of the year, was on the 1999 Oklahoma staff with Leach, both serving under Bob Stoops.

When reports surfaced in late November of this season that Kansas officials were investigating Mangino’s alleged mistreatment of players, Leach, during his weekly conference call with reporters, came to Mangino’s defense.

“Nobody truly knows what went on in Kansas,” Leach said at the time. “But my suspicion is Mark’s in the middle of a witch hunt, which is unjustified.

“Heaven forbid somebody should ask the guys to pay attention and focus in, and for the sake of all his teammates and coaches and everybody else, pay attention. Well, there’s different ways to ask a guy to do that, and sometimes after you’ve asked him a number of times, you raise the bar.”

In the Mangino case, Leach and others noted, player complaints about their treatment only came to light when the program hit a losing spell.

“The interesting thing to me is all the (reports) went from (Mangino) hit some guy in the face to, ‘Well, he didn’t even touch anybody, but he did say mean things to them,’ ” Leach added.

“A mean man told some players something they didn’t want to hear. Well, there’s a mean man in Lubbock who tells people stuff they don’t want to hear, too, and that’s part of it.”

As the Leach saga played out in a dizzying 48-hour span this week, Cotton Bowl coaches Mike Gundy of Oklahoma State and Houston Nutt of Ole Miss were more than hesitant to offer a reaction.

“I think the young men out there want discipline and structure and accountability,” Gundy said. “You can coach them as hard as you want to if they know you care about them and you’re going to do whatever you can to make them a better person off the field and bring them along on the field.”

Said Nutt, whose father, Houston Sr., was a coach for 34 years: “I will never hire anyone unless I would want him to coach my son. We tell our players all the time, ‘We’re going to coach you very hard.’ Off the field, we’re going to talk about fishing, basketball, girlfriends or family.”

Earlier this season, Leach wondered aloud whether some of his players were being adversely influenced by their “little fat girlfriends.” At the time, most media and fans laughed.

Teaff said the overwhelming majority of coaches he knows entered the profession for the same reason he did – to mold young people in a positive way.

But some coaches who started soon after World War II or the Korean or Vietnam wars, Teaff noted, believed that military-training techniques like physical confrontation and cursing were effective.

“But that didn’t last,” he said. “Those guys are long gone, and that philosophy is long gone.”

Teaff noted that college football coaching is personality driven. “Each coach handles things in a different way. There’s no standards. You can’t cookie-cut a coach and his personality.”

And these days, Teaff said, if there is an incident between coach and player, “we have instantaneous media, the Internet; you have every detail of every aspect looked at and magnified.”

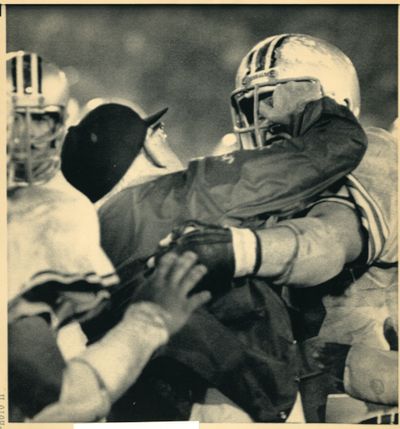

When Hayes on Dec. 29, 1978, punched Clemson’s Bauman after the nose guard’s game-clinching interception, many TV viewers saw it live, but announcers Keith Jackson and Ara Parseghian missed it. Replays also failed to catch the punch.

That could never happen now, of course. Teaff agrees that the Hayes incident changed the way fans and media perceived tough-approach coaches.

“The Good Lord and everybody saw that on television,” he said. “What made it so interesting is Woody went to his grave and never believed he actually did that.”