The Long Rangers

Shooters take heat for taking 1,000-yard shots at big game

Dave Powers has a foot firmly planted at opposite ends of the hunting spectrum. He’s an accomplished archery hunter who has taken several trophy animals after calling or stalking the animals to close range.

But the gunsmith who lives near Orofino, Idaho, also counts himself among a growing number of hunters taking animals with custom-made rifles at distances of 1,000 yards and beyond.

It’s a small and controversial form of hunting that often has participants shooting from one ridge to another at fantastic distances.

“It’s getting more and more acceptable,” he said of long-range hunting that some people find distasteful and equate with target shooting at live animals. “You are still going to have a lot of people say ‘That ain’t hunting’ and they are probably right. It’s not sneaking through the woods like bow and arrow (hunting) I guarantee, but it is an awful lot of fun.”

Many see it as violating the ethics of fair chase.

Keith Balford, director of marketing for the Missoula-based Boone and Crockett Club, said the organization that compiles record books for trophy animals has no regulations against taking animals at long ranges.

But he worries long-range hunting could hurt the sport.

“We have not publicly come out and said here is the line in the sand,” he said.

“How do you do that? You can’t do that. Probably of more concern to the club and the bigger picture is what kind of message does this send to the nonhunting public. It’s a concern when the nonhunting public sees this and says, ‘Is this hunting or just shooting?’

“Yes, there are skills involved in marksmanship and the ability to do that kind of shooting, but at the same token, you are kind of turning animals into targets.”

Long-range hunting takes a great deal of devotion for participants to acquire the skill set to make shots at great distances. It also requires hunters to acquire expensive equipment, including high-powered custom rifles, top-of-the-line scopes and laser range finders. They must become skilled in loading and testing their own ammunition and calculating factors such as bullet coefficients.

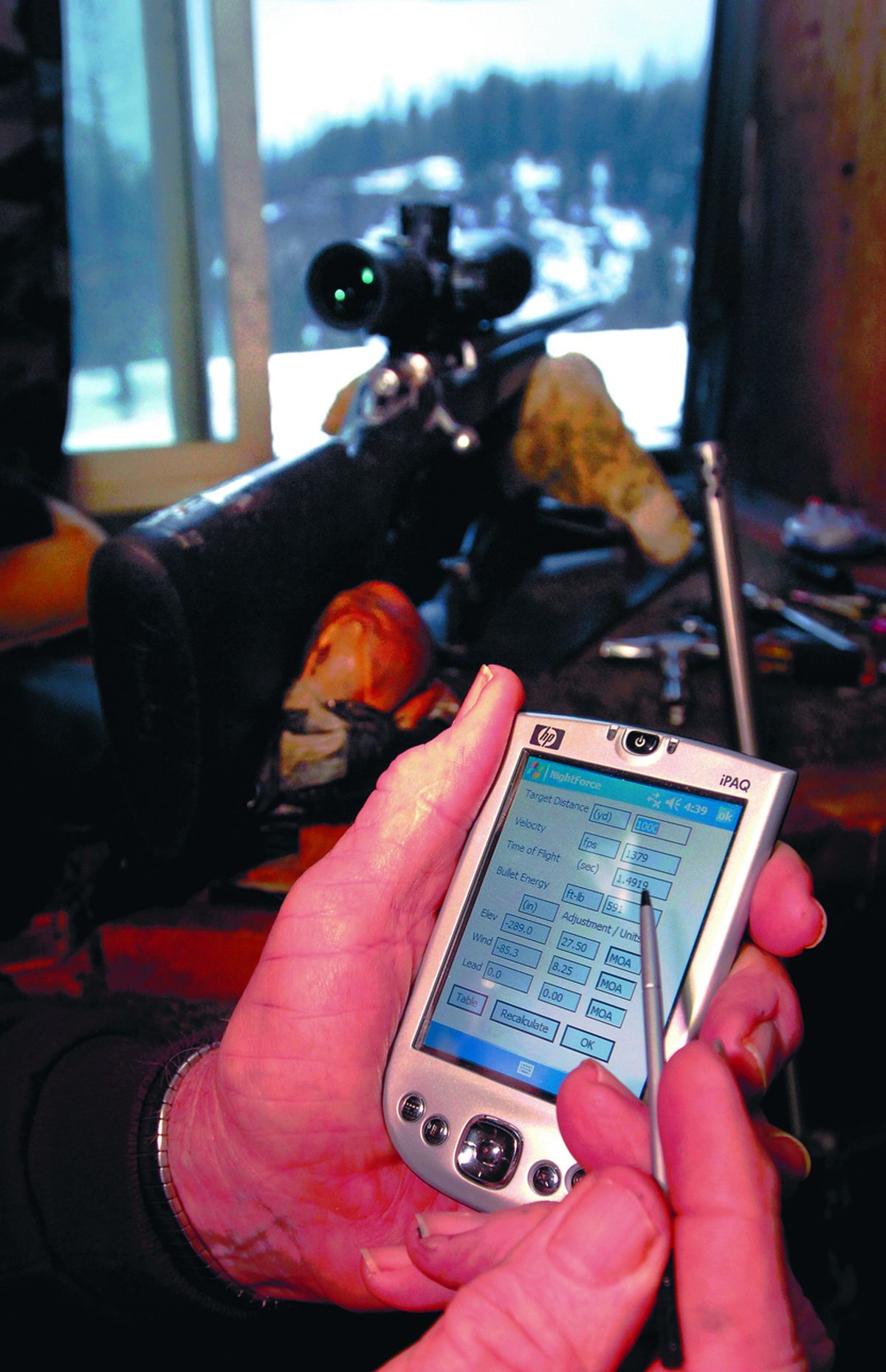

Powers, who builds long-range weapons at his home, has a handheld computer that helps him factor in multiple variables such as distance, wind speed, and the speed and weight of bullets to make the shots.

He punches in all the variables and the device tells him how to adjust his scope so it’s on target. Once a hunter acquires the skills, he said making the shots is easy – as long as the environmental variables are not too extreme.

“Wind is your biggest enemy,” he said. “If there is wind, you just don’t shoot. If you are not 100 percent sure, just don’t shoot.”

He said some hunters are capable of pulling off 1,000-yard shots under good conditions. Beyond that it becomes more difficult.

Although technological advancements such as quality optics have made long-range shooting easier and more popular, it isn’t new.

In the early 1990s, the Idaho Fish and Game Commission passed regulations requiring hunting rifles to weigh less than 16 pounds. Today’s rifles in 7mm and .338 calibers typically weigh about 13 pounds. The action to impose rifle weight restrictions was taken in response to hunters using mounted .50-caliber rifles to shoot elk from one ridgetop to another in the upper Clearwater Basin.

Keith Carlson, of Lewiston, served on the commission at that time and said there was a cry from the public to regulate long-range hunting. In his mind there are a number of things to worry about, including fair chase, making clean kills and following up on apparent misses.

“We just didn’t consider it to be a reasonable sporting proposition to shoot at that range,” he said. “You can shoot a deer at 150 yards and spend a whole lot of time to find where it dropped. If you add two ridge tops between it makes it a lot more difficult.”

He also noted that animals can move in the second or more it takes a bullet to travel 1,000 yards.

Jeff Huber, vice president of Nightforce Optics, an Orofino-based business focusing on long range and precision rifle scopes, said hunters must be sure they have a reasonable chance of hitting their targets and must use bullets that properly expand on impact at the low speeds associated with long-range shots.

Ethical long-range hunting “really comes down to a guy knowing his limitations and the proper practice and experience and getting to the point where you have an 80 percent hit probability or better,” he said.

Many hunters would question the 80 percent threshold.

For wildlife managers, regulating how far is too far is difficult, and enforcement is even tougher.

“Where do you draw the line and how many people are really doing it?” said Jim Unsworth, Idaho Department of Fish and Game deputy director in Boise. “We try to not burden the rules with too many specific regulations. On the other hand, we hope people will be responsible hunters and take reasonable shots and the main thing is following up on the shots after taking them and making sure they haven’t wounded an animal, and do a good job on retrieval.”

Hunting rules and ethics require hunters to follow up on shots when it is not clear if an animal has been hit. Some critics of long-range hunting question whether hunters who are 1,000 yards away from their targets will take the time to close the distance and search for evidence of a hit.

Powers agrees that follow-up is essential at any range, but he suggests that few animals are wounded and lost by long-range hunters who know what they are doing.

“A lot of people grab a gun and a big scope and think they can actually be 100 percent at 1,000 yards and there is no way,” he said. “You certainly need to know exactly what your gun is doing and you need a lot of shooting time. You need a good shooting platform. A lot of guys are resting on the side of a pickup or a tree. Some of them are making good shots doing that, but over the long haul they are not going to be 100 percent.”

Preferring to archery hunt, Powers doesn’t shoot animals at long ranges very often. Instead, he participates in long-range target-shooting competitions and is a member of the Missoula 1,000 Yard Bench Rest Association.

Powers has won some competitions and his wife, Donita, has the second-best group of 10 shots ever recorded at 1,000 using a gun weighing less than 17 pounds. She put all 10 shots in a 3.9-inch diameter.

Powers said 1,000-yard matches are typically won with groups in the 4- to 5-inch-diameter range.

Rarely a day goes by, Powers said, that someone doesn’t contact him who is interested in building a long-range rifle. For those who are, he said he is willing to introduce them to the sport, and target and match shooting is a great way to learn.