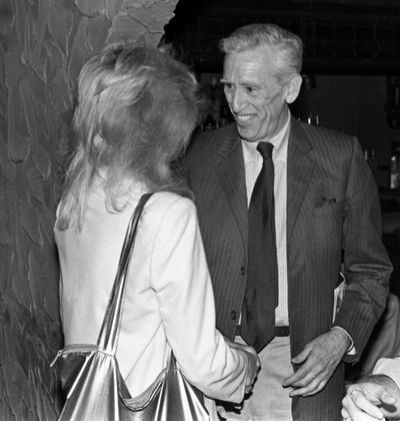

Author of ‘Catcher in the Rye’ dies at 91

J.D. Salinger’s novel influenced generations

NEW YORK – J.D. Salinger, the legendary author, youth hero and fugitive from fame whose “The Catcher in the Rye” shocked and inspired a world he increasingly shunned, has died. He was 91.

Salinger died of natural causes at his home on Wednesday, the author’s son, actor Matt Salinger, said in a statement from Salinger’s longtime literary representative, Harold Ober Associates, Inc. He had lived for decades in self-imposed isolation in a small, remote house in Cornish, N.H.

“The Catcher in the Rye,” with its immortal teenage protagonist, the twisted, rebellious Holden Caulfield, came out in 1951, a time of anxious, Cold War conformity and the dawn of modern adolescence. The Book-of-the-Month Club, which made “Catcher” a featured selection, advised that for “anyone who has ever brought up a son” the novel will be “a source of wonder and delight – and concern.”

Enraged by all the “phonies” who make “me so depressed I go crazy,” Holden soon became American literature’s most famous anti-hero since Huckleberry Finn. The novel’s sales are astonishing – more than 60 million copies worldwide – and its impact incalculable. Decades after publication, the book remains a defining expression of that most American of dreams: to never grow up.

Salinger was writing for adults, but teenagers from all over identified with the novel’s themes of alienation, innocence and fantasy, not to mention the luck of having the last word. “Catcher” presents the world as an ever-so-unfair struggle between the goodness of young people and the corruption of elders, a message that only intensified with the oncoming generation gap.

“‘Catcher in the Rye’ made a very powerful and surprising impression on me,” said Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Michael Chabon, who read the book, as so many did, when he was in middle school. “Part of it was the fact that our seventh-grade teacher was actually letting us read such a book. But mostly it was because ‘Catcher’ had such a recognizable authenticity in the voice that even in 1977 or so, when I read it, felt surprising and rare in literature.”

“Many readers were created by ‘The Catcher in The Rye,’ and many writers, too,” said “Everything Is Illuminated” novelist Jonathan Safran Foer. “He and his characters embodied a kind of American resistance that has been sorely missed these last few years, and will now be missed even more.”

The cult of “Catcher” turned tragic in December 1980 when crazed Beatles fan Mark David Chapman shot and killed John Lennon, citing Salinger’s novel as an inspiration and stating that “this extraordinary book holds many answers.” A few months later, a copy of “Catcher” was found in the hotel room of John David Hinckley after he attempted to assassinate President Reagan.

Salinger’s other books don’t equal the influence or sales of “Catcher,” but they are still read, again and again, with great affection and intensity.

The collection “Nine Stories” features the classic “For Esme – with Love and Squalor,” the deadpan account of a suicidal Army veteran and the little girl he hopes, in vain, will save him. The fictional work “Franny and Zooey,” like “Catcher,” is a youthful, obsessively articulated quest for redemption, featuring a memorable argument between Zooey and his mother as he attempts to read in the bathtub.

“The Catcher in the Rye” became both required and restricted reading, periodically banned by a school board or challenged by parents worried by its frank language and the irresistible chip on Holden’s shoulder.

“I’m aware that a number of my friends will be saddened, or shocked, or shocked-saddened, over some of the chapters of ‘The Catcher in the Rye.’ Some of my best friends are children. In fact, all of my best friends are children,” Salinger wrote in 1955, in a short note for “20th Century Authors.”

“It’s almost unbearable to me to realize that my book will be kept on a shelf out of their reach,” he added.

His last published story, “Hapworth 16, 1928,” ran in The New Yorker in 1965. By then, he was increasingly viewed like a precocious child whose manner had soured from cute to insufferable. “Salinger was the greatest mind ever to stay in prep school,” Norman Mailer once remarked.

In 1999, New Hampshire neighbor Jerry Burt said the author had told him years earlier that he had written at least 15 unpublished books kept locked in a safe at his home.

“I love to write and I assure you I write regularly,” Salinger said in a brief interview with the Baton Rouge (La.) Advocate in 1980. “But I write for myself, for my own pleasure. And I want to be left alone to do it.”

The mystery of the safe continued Thursday. Salinger’s representative at the Ober agency, Phyllis Westberg, declined comment on whether the author had any unpublished work. Spokeswoman Heather Rizzo of Little, Brown and Co., Salinger’s longtime publisher, said she had “no news on future releases.”

Jerome David Salinger was born Jan. 1, 1919, in New York City. His father was a wealthy importer of cheeses and meat and the family lived for years on Park Avenue.

Like Holden, Salinger was an indifferent student with a history of trouble in various schools. He was sent to Valley Forge Military Academy at age 15, where he wrote at night by flashlight beneath the covers and eventually earned his only diploma. In 1940, he published his first fiction, “The Young Folks,” in Story magazine.

He served in the Army from 1942 to 1946, carrying a typewriter with him most of the time, writing “whenever I can find the time and an unoccupied foxhole,” he told a friend.

Holden first appeared as a character in the story “Last Day of the Last Furlough,” published in 1944 in the Saturday Evening Post. Salinger’s stories ran in several magazines, especially The New Yorker, where excerpts from “Catcher” were published.

The finished novel quickly became a best seller and early reviews were blueprints for the praise and condemnation to come. The New York Times found the book “an unusually brilliant first novel” and observed that Holden’s “delinquencies seem minor indeed when contrasted with the adult delinquencies with which he is confronted.”