What if disaster struck?

Imagine consequences if major earthquake or other natural catastrophe rocked West Side

Two weeks ago, Hawaii came to a standstill when oceanographers warned that the Chilean earthquake could culminate in a killer tsunami.

Residents and tourists cleared the beaches. Sirens blew. Families fled to higher ground.

The tsunami didn’t materialize, but it got us thinking: What disaster would force the Inland Northwest to a similar standstill?

Short of a nuclear incident or an asteroid hit, experts say we’re relatively safe.

But if a blowout natural disaster – most likely an earthquake – hits the West Side of Washington state, it could change the Inland Northwest forever.

“We would face a humongous challenge to restore the state,” said Rob Harper, public information officer with the Washington Emergency Management Division. “It would be a daunting task.”

Close to home

Severe local storms, wildfires and “hazmat” – a jargon term meaning chemical spills – comprise the top three threats to the Inland Northwest, according to local emergency-preparedness studies.

Some examples: the Ice Storm of 1996, and our two severe snow events in winters 2008 and 2009. Firestorm, in 1991, was the region’s most memorable major fire in recent history, though wildfires pose a perennial hot-weather hazard.

The Inland Northwest has yet to experience a widespread hazmat disaster, but the potential surrounds us.

“What’s hazmat? Ethyl-methyl-bad stuff,” explained Tom Mattern, deputy director of the Spokane Emergency Management Department.

“It could be a gas pipeline bursting. Sometimes the pipelines run under the river, and if one of those would bust in the river, it wouldn’t be good.”

Mattern also said that if a train carrying hazardous gas or liquid crashed here, and 30 mph winds were blowing that day, “Spokane would be a mess.”

In the last two decades, the region’s severe storms and wildfires certainly disrupted daily life. School was canceled. Power outages reported. Homes and businesses were damaged and destroyed.

But the region didn’t come to a complete standstill, and a hazmat disaster probably wouldn’t force a standstill, either.

“I have never seen anything come to a total stop here, even with everything we’ve experienced,” said Bob Pittsley, preparedness specialist for the Kootenai County Office of Emergency Management.

“We’re inland, and hurricanes are related to coastal areas. And we’re not in any tornado alley. We’re just lucky, I guess.”

When Mount St. Helens blew May 18, 1980, the dust cloud that traveled to the Inland Northwest choked off the ability to use cars and trucks, and many people were trapped indoors.

Mount St. Helens – the Inland Northwest’s greatest disaster to date – originated on the state’s West Side. That’s where the next big one is likely to originate, too.

The hypothetical

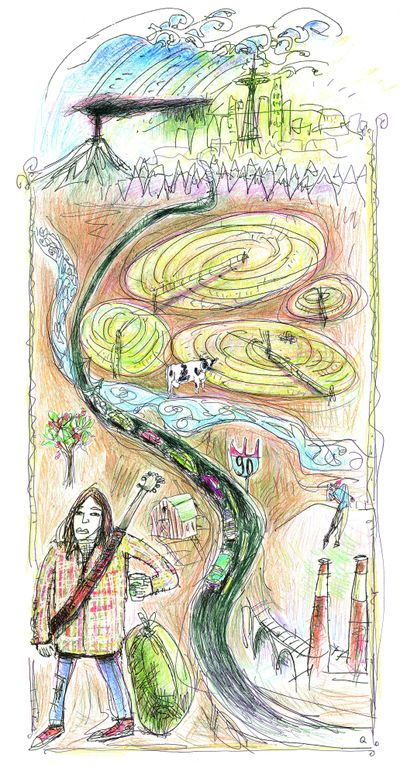

Here’s a next-big-one hypothetical, melding several scenarios discussed with the half-dozen emergency preparedness experts interviewed for this story:

An earthquake hits Western Washington when a fault line, stretching from Northern California to British Columbia, wakes up after a 300-year snooze. It’s a magnitude-9 earthquake, more ferocious than recent earthquakes in both Haiti and Chile.

Freeways buckle. Houses collapse. A tsunami pummels the coastline.

In Eastern Washington and North Idaho, residents feel aftershocks. These aftershocks are as strong as, and in some cases stronger than, the five dozen quakes, ranging from magnitude-1 to magnitude-4, that rattled Spokane over several months in 2001 and 2002.

Medical facilities are compromised throughout the West Side, and Inland Northwest medical centers take in injured survivors.

The first preference is to relocate non-injured evacuees in the less damaged parts of Western Washington, and then in outlying counties, including those east of the Interstate 5 corridor – but definitely within Washington, so residents remain under state laws and state services.

And Oregon’s in deep trouble anyway, because the earthquake cracked open their coastal communities, too.

Evacuees leave the West Side by air, car and rail, though roads and rail lines are heavily damaged in some places.

The American Red Cross is at the forefront of sheltering evacuees. Before the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, B.C., the Inland Northwest chapter of the Red Cross participated in a “tabletop exercise” detailing an evacuation plan into the Inland Northwest, in the event of a terrorist attack or another disaster in Vancouver.

The plan wasn’t needed for the Olympics, but it’s activated now: Some of the West Side residents who drive east on Interstate 90 stop when they run out of money and gas. Ellensburg, Moses Lake and Ritzville fill with evacuees.

Still, the majority end up in Spokane. Family and friends offer food and beds, and Red Cross shelters fill rapidly.

Some evacuees continue driving into North Idaho, because in disasters, people relocate anywhere they feel welcome.

During Hurricane Katrina, for instance, about 5,000 evacuees gravitated to Washington state. They weren’t sent here by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. They were invited by family members, church groups and universities.

Just as New Orleans is still recovering from Katrina – more than four years after the disaster – the length of stay for earthquake refugees in this hypothetical scenario stretches into years.

Some settle in the Inland Northwest permanently, scarred and scared by the West side’s so-called “ring of fire” dangers – earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanoes.

The increase in population in Eastern Washington and North Idaho inflates the housing market, crowds the region’s schools and strains social service agencies. But economic opportunities increase as some commerce patterns shift away from the West Side.

Inland Northwest leaders market the region as a safe place to live and do business. Severe storms, wildfires and hazmat seem like child’s play compared to earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanoes.

Be prepared

Disaster planning experts feel heartsick watching the human devastation after events such as Katrina, Haiti and Chile.

But these catastrophes help them spread their main message: Be prepared.

“People start thinking, ‘Wow, I wonder, could it happen here? What would I do?’ ” said Brenda Lawlor, disaster services coordinator with the American Red Cross Inland Northwest Chapter.

“We encourage people to be Red Cross-ready. We have all kinds of checklists and preparedness tips, including being ready with CPR training.”

The preparation mantra? Store three days’ worth of water and food and invest in an alternative power source.

Plan as if “the first 72 hours you are basically on your own,” advised Bill Hansen, resource coordinator with Spokane Emergency Management Department.

And if that blowout disaster strikes Western Washington anytime soon?

Prepare the guest room. Folks are on their way.