Hang gliding in the Inland Northwest – the “green” machine

Da Vinci may have sketched flying, but Spokane resident does it

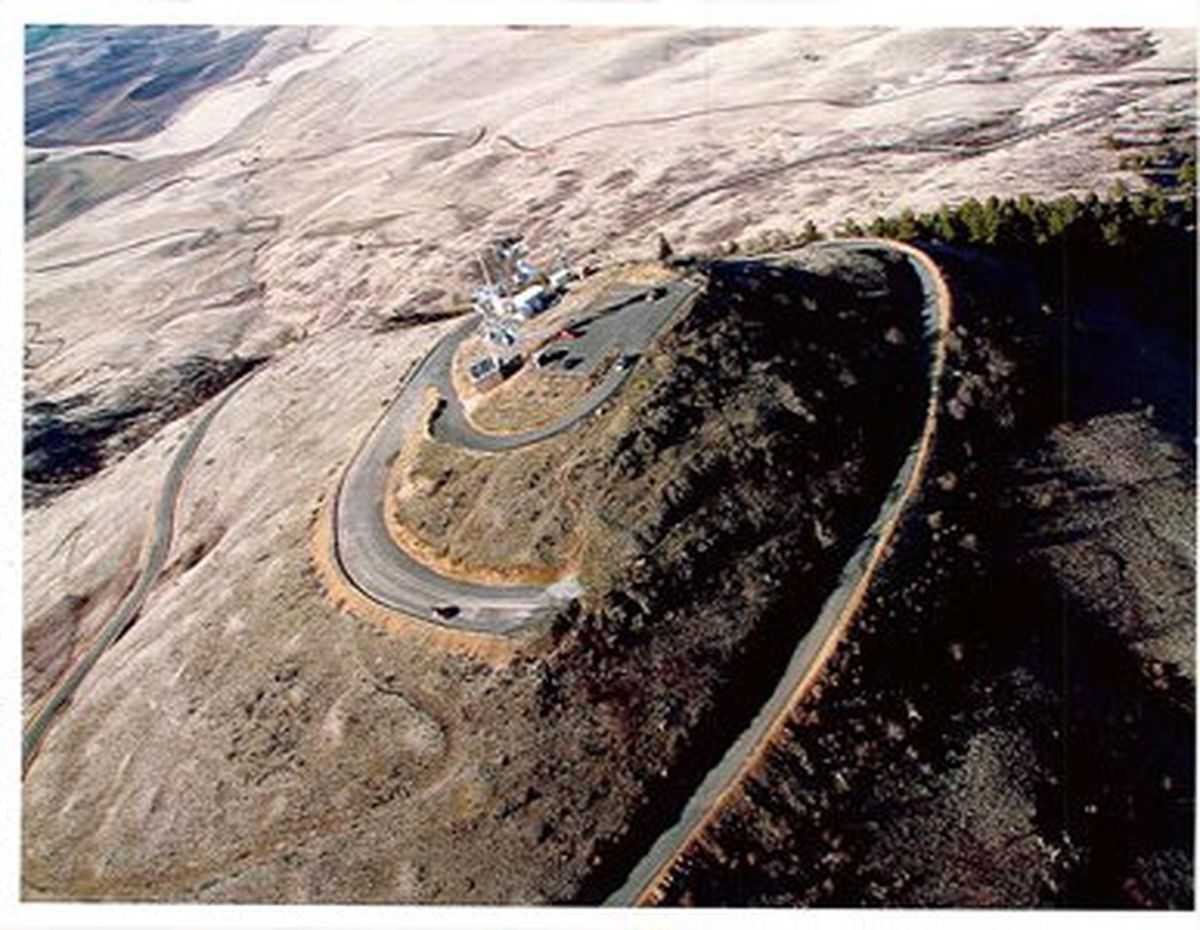

It makes sense, when floating around Steptoe Butte, that Icarus would have wanted to defy gravity, impugn the gods and challenge the sun to soar closer to the ionosphere. Maybe he wanted to find the great Pacific Flyway.

For one Inland Northwest seasoned hang glider, who for more than three decades has instructed hundreds of people to become pilots, there’s no place closer to nirvana than wind and sky while red-tail hawks come horning in on your thermal.

“I guess it’s in my blood,” said Dale Sanderson, graduate of West Valley High School and owner, operator and instructor for Inland Air Sports, which has been teaching novices and intermediates how to soar like birds. “I’ve always felt like I was flying in my dreams.”

Call it mystical, or “one with drafts, wind sheers and thermals,” but Sanderson has logged more than 4,650 hours hang gliding since first trying it on his own while stationed in the U.S. Air Force in Arkansas. He watched wild hang gliders in the Ozarks, on Petit Jean Mountain, in 1977, and has been hooked ever since.

It’s a far cry from the early days when Sanderson read a book, bought a used hang glider, and strapped on every sort of motocross body armor he could muster. Then he leaped off a ridge overlooking an illegal dump near where he was stationed.

There’s an obvious spiritual thing when talking to Sanderson and others who get into these fast climbs, sometimes 1,200 feet per minute, while hitting cloud bases 10,000-14,000 feet, sometimes higher.

I was with him while he was training Coeur d’Alene architect Jack Simpson near Fish Trap Lake. With wide eyes and intense body language, Simpson tried flight after flight to get the feel of one of the most naked ways to move oneself with a “machine.”

It’s all body language, as I tried the huge training glider, a Condor, designed to have extra sail to capture any sort of light wind for beginners to feel lift.

The sport’s equipment has gone through five generations of radical design changes, Sanderson said, and the first Rogallo “wing,” named after a NASA engineer (Francis Rogallo) working on spaceship recovery systems, was the progenitor.

Those were dangerous days, and I remember living in Arizona when several friends caught killer thermals in the Sonora desert, so corkscrewy and intense that they went past 20 circling California buzzards at 15,000 feet. Then the sheer, and the human squadron got pushed into the side of the Catalina Mountains, killing two out of the six.

Sanderson is all about safety and training, using a hill like a ski instructor would use the bunny slope to make sure the body-mind-elements syncopation is at least functional for students.

He’s been on a multitude of flights around the country, yet he still likes Tekoa and Lake Chelan, Wash. Htold me about a husband and wife team from Battle Creek, Mich., who west for one of Inland Air Sports’ five-day from-no-experience- to- beginner-to-novice class.

The problem was that the wife had never been on a mountain, and while she did well on the training hills, Sanderson said she white knuckled Dale all the way up Steptoe Butte. After he husband did a great tandem run and solo flight, the woman still wanted to continue.

“She screamed the entire [tandem] flight, and when we approached the ground, she wanted me to slow down.” As anyone who knows about gliding or flying, you want that energy and speed to be big when approaching a landing so the flair back brings the sail into as much cupping wind as possible so the pilot ends up on his feet, not forehead and elbows.

Sanderson likes talking about the sport that takes its physics from airplane flying, but also keeps returning to his and his wife Teresa’s dream of owning 80 acres on the Palouse with a full organic vegetable growing operation.

Plus, it would include several training hills and maybe a small mountain, sort of a hang gliding B&B catering to both seasoned and new hang gliders. He’s even designing a launch tower with cables and electric motors to run line out 4,000 feet so gliders can get some air time, from 25 feet up for a newbie, to 600 feet or more for experienced pilots, while tethered to this contraption of his own design.

Hang gliding is really a green sport, compared to a plane or ultra-light. It’s an avocation and hobby that ties into looking at the land, from above, and appreciating the dynamics of wind hitting geography. Plenty of wildlife is espied from high above.

Sanderson prefers the quiet, or his commune with, say, a raven, a species of bird that digs flying with him, including some gnarly thermals.

“Both of us were getting pretty battered up there, trading places in the thermal … the raven was even upside down showing off his talons.” For Sanderson, that is more than worth the risk of spiraling to his death. “The bird made eye contact, playing off my glider’s wing tip,” he said.

Sanderson emphasized that it’s pretty safe sport. Simpson, from Idaho, was getting every tip possible for his next adventure –to Austin, Texas, and trying it there.

For Sanderson, hitting 60 miles an hour in his Falcon, or having a good hour flight on a clear day, are his ways of touching the heavens like Icarus attempted. He defies the gods or muses, sure, but always comes back down to terra firma, with a smile on his face and the aerial sea’s hidden tides and rip-currents and undertows deep within.

For flight information, contact inlandair@msn.com, or call (509) 535-8119. For more background on hang gliding and para-gliding: < a> href=”http://www.ushpa.aero/default.asp”>

http://www.ushpa.aero/default.asp