Widow of Spokane pilot returns to village where plane went down

This spring, a French village honored the American crew of a World War II bomber at a memorial dedication attended by the Spokane widow of the plane’s pilot and their son.

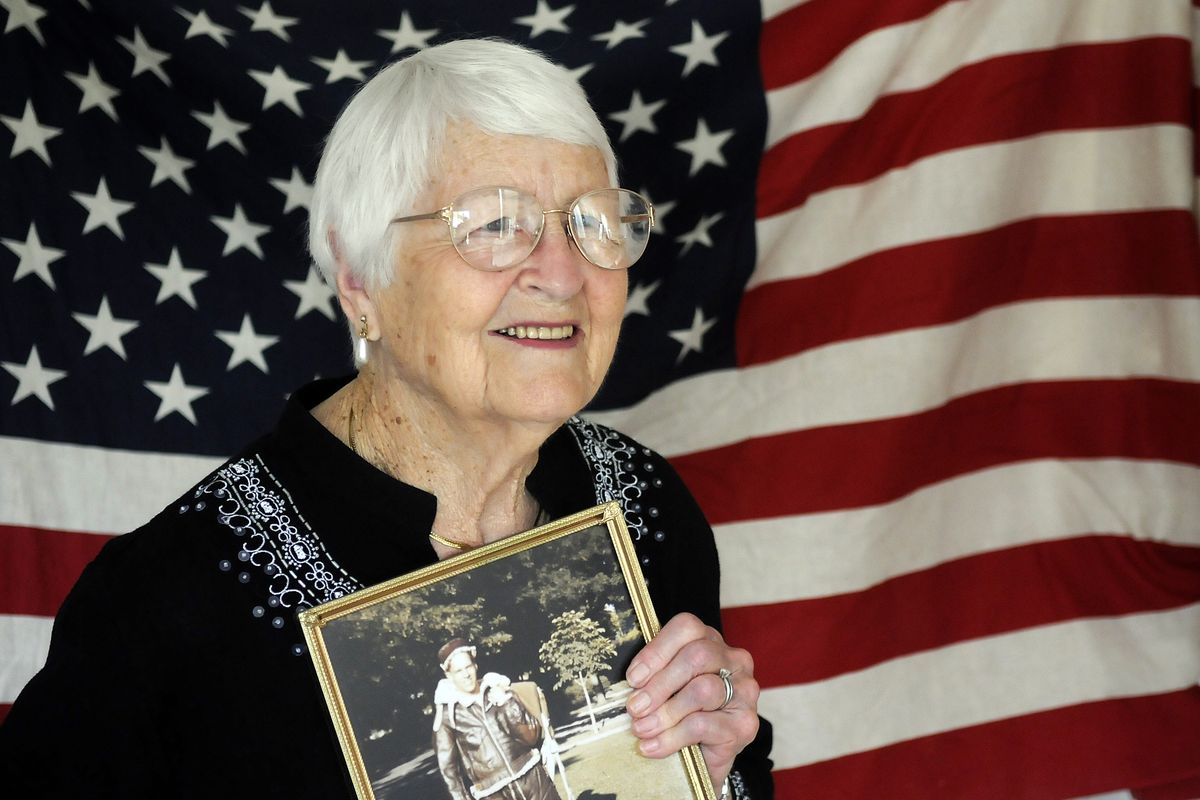

“They are a people who still remember,” said Pauline “Paula” Lorenzi, 88, one of 17 Americans and nearly 500 French to attend the May 28 ceremony in Le Cardonnois, France.

There, 67 years ago, some incredibly brave people did a wonderful thing for Lorenzi’s husband, Robert O. Lorenzi. At the time he was a young second lieutenant whose B-17 Flying Fortress was shot down while returning from a bombing run over Frankfurt, Germany.

The events of Feb. 8, 1944, were documented in a book by French author Dominique Lecomte titled, “Tail End Charlie,” named for the location of Lorenzi’s plane in the bombing formation. Much of the information for the book came from the memoirs of Lorenzi, who died in 2007.

Lecomte and the mayor of Le Cardonnois invited Paula Lorenzi to France, and she was accompanied by her son, David.

“I was able to stand at the spot my dad’s parachute landed, see the barn he was hidden in, the room the doctor removed the bullet from his foot,” David Lorenzi said.

The Spokane mother and son also met some of the remaining French citizens who put themselves in extreme danger under German occupation to save four Americans who literally fell into their lives.

According to an account of that day by Lecomte, the bomber and its crew, part of the 452nd Bomb Group, 8th Air Force, departed England to attack Frankfurt, where the plane was heavily damaged by flak. On the return flight it was attacked by German fighter planes over France.

The bombardier, 2nd Lt. Abraham Rosenthal, of Birmingham, N.Y., was killed and other crew members were injured. In addition, the starboard engines had been hit, resulting in loss of power.

Lorenzi managed to drop the crippled plane into the clouds where the fighters did not follow. But the B-17 continued to drop below cloud cover.

Lorenzi, who was wounded in the foot, gave the order to abandon the burning aircraft, which he struggled to keep under control.

“Holding the joystick in his right hand, Lorenzi slipped out of his seat and managed to stand on his right foot. He pulled the joystick backward, put the Fortress into a climb, let go of the joystick, got down on his knees and dived head-first out of the forward escape hatch,” according to a translation of Lecomte’s account.

Lorenzi, the last to parachute, landed near some woods by the road from Welles to Perennes.

Two young women returning from a funeral, Lucienne Mortier, 24, and her cousin Charlotte Bizet, 30, helped Lorenzi to the farm of Mortier’s parents, avoiding German troops looking for the B-17 crew.

Lorenzi hid under some hay in a barn before being taken after nightfall to the Mortiers’ farmhouse, where he was fed and treated by a doctor.

Later, Lorenzi learned that five of his crew had been taken prisoner by the Germans. Besides Lorenzi, three others were rescued by the French: the copilot, 2nd Lt. Robert Costello, of New York City; navigator 2nd Lt. Paul Packer, of Chicago; and flight engineer Staff Sgt. Edward Sweeny, of Brooklyn, N.Y.

The four were hidden in different houses in the area about 50 miles north of Paris, but eventually they were taken to the home of Pierre Coulon, a member of the French Resistance, where they hid for about 12 days.

During their time at Coulon’s, the crewmen were tested by a Resistance agent, who incorrectly stated that Spokane was on the East Coast of the United States in order to discern whether Lorenzi was a German spy.

The airmen later were separated, and Lorenzi was hidden in the home of a woman named Dorez, whose 16-year-old daughter, Jacqueline, knew enough English to serve as interpreter. Lorenzi stayed with the Dorez family about four weeks until he was spirited to Paris, where he, Costello, Packer and Sweeny entered an elaborate escape network complete with forged identification papers.

One dark night, the four crewmen were taken in small boats to a British gunboat waiting to cross the English Channel to Dartmouth and safety.

Lorenzi later was stationed in Roswell, N.M., were he met Paula, who was working in a jewelry store. The couple married three months later on Jan. 19, 1945. They returned to his hometown, Spokane, where Lorenzi had graduated from North Central High School.

He was called up in 1951 during the Korean War, and also flew a C-47 in Vietnam in 1967.

Lorenzi retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1968 as a lieutenant colonel, decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters and the Purple Heart.

In 1992, the couple traveled to France where they met many of the people who rescued Lorenzi, including Lucienne Mortier, who pointed out to them where the plane had gone down.

Also attending the dedication in France in May were Rosenthal’s widow, Dorothy, and her daughter, Gale. Sgt. Donald Kirby, of Columbus, Ohio; the radio operator who was among those taken prisoner, is the only surviving member of the crew.