Killebrew matched athletic strength with off-field kindness

MINNEAPOLIS – Think of the phrases we use to praise modern-day athletes. They possess “killer instinct.” They “stick the dagger” into the opponent. They display “swagger” and “athletic arrogance.”

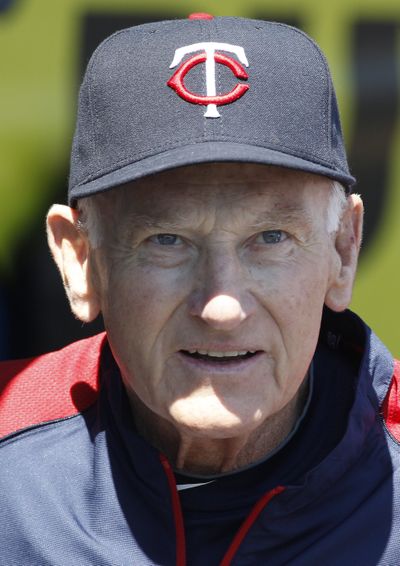

When Harmon Killebrew died in Arizona on Tuesday, the sporting world may have lost its foremost gentleman. The greatest Twin did not require false machismo to become one of the greatest home-run hitters in baseball history. Harmon Killebrew did not require pressure to exhibit grace.

Will we ever encounter his kind again?

Killebrew’s era predated steroid scandals and sporting paparazzi. When he played, players often lived in middle-class neighborhoods. Even if a current player possessed Killebrew’s Everyman attitude, he would be distanced from much of society by the invisible fencing of wealth and fame.

Naivete and nostalgia are often weaknesses. In remembrance of Killebrew, allow those of us who grew up watching him and his peers a moment of sepia-toned remembrance.

I spent part of my youth living near Baltimore. One of my strongest memories is of a midseason game the Twins played against the Orioles.

Baltimore third baseman Brooks Robinson was my boyhood idol, in part because of his fielding brilliance, in part because he looked so average. Brooksie, with his skinny arms and hangdog face, could have been your middle-age neighbor, had your middle-age neighbor been granted superhuman hand-eye coordination by a higher power.

A line drive would head down the third-base line, and Robinson’s hands would move faster than a Times Square con artist’s, and suddenly the ball would be bouncing into Boog Powell’s outstretched glove for another improbable out, and you got the feeling that as soon as the game ended, Robinson would resume mowing his lawn.

One night, Robinson and the Orioles faced the Twins at old Memorial Stadium. When Robinson left the field, he was replaced by a player who looked less likely to become a Hall of Fame ballplayer – a short, thick, balding player, who looked like a neighborhood butcher playing for the local slow-pitch softball team.

Then Killebrew plodded to the plate, launched a home run deep into the bleachers, dropped his bat, watched the ball fly and started his slow navigation around the bases.

“Oh, he would watch the ball,” Tony Oliva said. “He would hit it so far, so high, and he would stand there and watch it. Pitchers would throw at him, hit him, for doing that, but I never saw him react. He would just take first base like nothing happened.”

I did not grow up in Minnesota following Killebrew, but I know what it is like to have given my young heart to a great ballplayer when baseball was king, when we erected pedestals for our favorite ballplayers and left them there for eternity.

While it may seem inelegant to compare deaths, I believe that it hurts us more when we lose a great baseball player than when we lose other athletes.

Great baseball players, especially in Killebrew’s prime, were not occasional visitors to our homes. They were uncles, cousins, friends.

They were there every day in the morning paper. They were there, on television, more often than any other athletes. They were the people you followed late at night, with a transistor radio tucked under your pillow, turned down just far enough that your parents could pretend you were sleeping.

Someday another player may replace Killebrew as the greatest Twin of all time. It is unlikely that another player will ever become so universally beloved and admired.

We called him “the Killer,” but that nickname matched the man only when a fastball was headed toward home plate. In life, he was the most gracious of the all-time greats, the most likely to leave someone he just met feeling privileged to shake his hand.

He never let us down.