40 years after skyjacking, new details on D.B. Cooper emerge

SEATTLE – It’s been a rich year for students of D.B. Cooper, the mysterious skyjacker who vanished out the back of a Boeing 727 wearing a business suit, a parachute and a pack with $200,000 in ransom money 40 years ago today.

An Oklahoma woman came forward to say Cooper may have been her uncle, now deceased. A new book publicized several theories, including one that Cooper was a transgendered mechanic and pilot from Washington state. A team that includes a paleontologist from Seattle’s Burke Museum released new findings this month that particles of pure titanium found in the hijacker’s clip-on tie suggest he worked in the chemical industry or at a company that manufactured titanium – a discovery that could narrow the field of possible suspects from millions of people to just hundreds.

Nevertheless, no one’s been able to solve the puzzle, or even determine whether Cooper survived his infamous jump.

“This case is a testament in a way to our enduring fascination with both a good mystery and a sense of wonderment – mystery because we still don’t know who this guy was, and wonderment that a guy could do something this bold – or stupid,” says Geoffrey Gray, whose book, “Skyjack: The Hunt for D.B. Cooper,” came out in August.

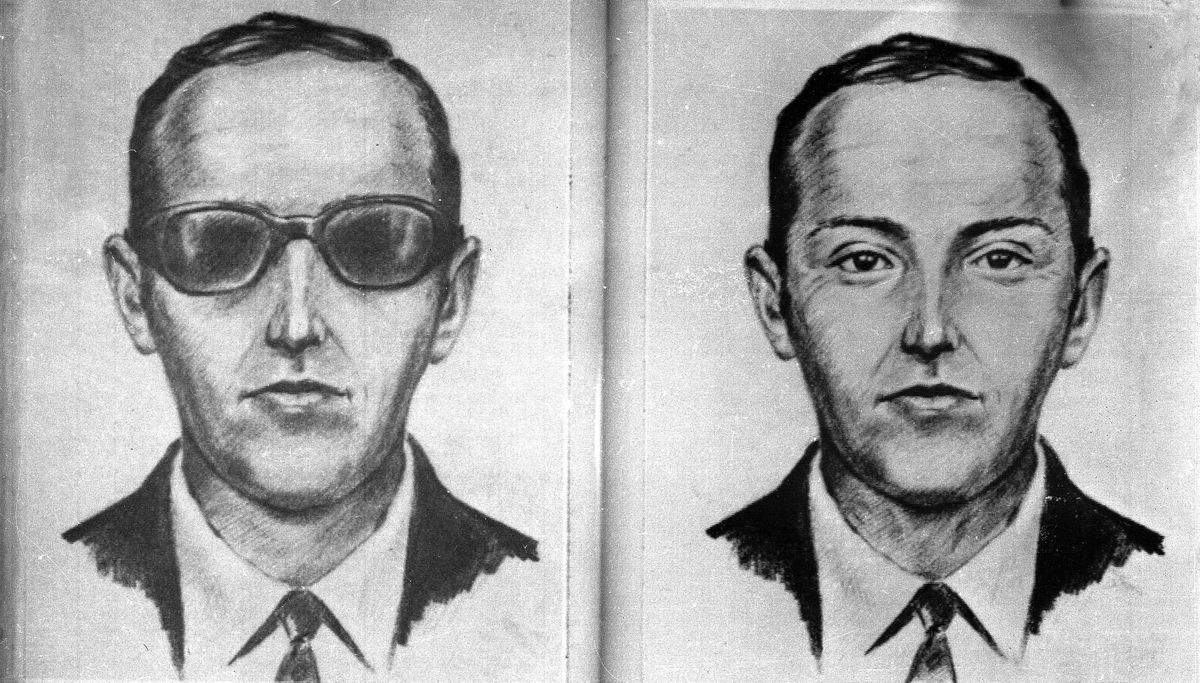

On Nov. 24, 1971, the night before Thanksgiving, a man described as being in his mid-40s with dark sunglasses and an olive complexion boarded a Northwest Orient Airlines flight from Portland to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. He bought his $20 ticket under the name “Dan Cooper,” but an early wire-service report misidentified him as “D.B. Cooper,” and the name stuck.

He sat in the back of the plane and handed a note to a flight attendant. She was so busy she didn’t read it until after takeoff: “Miss, I have a bomb and would like you to sit by me.”

He opened his briefcase, displaying a couple of red cylinders, wires and a battery, and demanded $200,000 in cash plus four parachutes. His demands were granted at Sea-Tac, where he released the 36 passengers and two of the flight attendants. The plane took off again at his direction, heading slowly to Reno, Nev., at the low height of 10,000 feet. Somewhere, apparently over southwestern Washington, Cooper lowered the aircraft’s rear stairs and dove into a freezing rainstorm.

No sign of Cooper has ever emerged, but a boy digging on a Columbia River beach in 1980 found three bundles of weathered $20 bills – Cooper’s cash, according to the serial numbers.

A few events are planned for Saturday to mark the anniversary, including a Cooper symposium at a Portland hotel, where sleuths will present their latest findings and theories – and serve as jurists for a Cooper-themed poetry contest.

Among those planning to attend is Marla Cooper, of Oklahoma City, who disclosed this year that she had provided a tip to the FBI about her deceased uncle. Relying on childhood memories, she recalled that her uncle Lynn Doyle Cooper had arrived at a family home in Oregon with serious injuries and that she overheard him talking about the hijacking.

Cooper says she’s optimistic the FBI will be able to match her uncle’s fingerprints to those involved in the case. The agency has said DNA testing did not match samples on the hijacker’s necktie, but that the finding did not necessarily rule out the lead.

“It looks rather promising that this case could very well be solved in the next few months,” Marla Cooper said.

Other Cooper enthusiasts aren’t so sure. Agents discovered numerous partial fingerprints on an in-flight magazine, but it’s unknown if any of those was Cooper’s. He appeared to be careful not to leave fingerprints and demanded the flight attendant return the bomb note he had given her.

Partial DNA samples were recovered from the plane, including on the clip-on tie that was left on the hijacker’s seat, but no one knows if the samples came from Cooper. The items that might have provided a definite DNA profile – the eight filter-tipped cigarette butts he chain-smoked during the flight – apparently went missing while in FBI storage in Las Vegas.

Many people, including Ralph Himmelsbach, the FBI’s lead agent on the case until his retirement in 1980, believed Cooper could not have survived. The temperature at 10,000 feet was 7 below zero, not including the minus-70 wind chill, and even if he survived the jump, he probably landed in the Columbia River or in rugged, wooded mountains at the onset of winter with no outdoor gear.

Tom Kaye, a paleontologist at the University of Washington’s Burke Museum, said his presentation at the symposium will suggest Cooper lived. The three bundles of money that were found on the Columbia River beach at Tena Bar were about 20 miles east – that is, upstream – of what Kaye believes was the plane’s flight path. If that’s so, the bundles couldn’t have gotten there “without mechanical or human intervention,” he said.

That the bundles of money were found together suggests they didn’t wash down to that spot from a tributary upstream, as others have suggested, he argues.

With the FBI’s blessing, Kaye’s team tested the tie and discovered the microscopic slivers of pure titanium. At the time, he said, titanium was much rarer than it is today. Titanium alloys were used in aircraft parts, but pure titanium was found only at companies that made pure titanium or at chemical companies which used it because of its corrosion-resistance.

Of course, that doesn’t mean the hijacker worked at one of those companies. He could have purchased the tie at a thrift shop just before the flight.

Following the symposium, some participants plan to head 39 miles north to a familiar stomping ground – the Ariel Store and Tavern in Ariel, Wash., in the heart of Cooper country. The store has hosted an annual Cooper celebration for 22 years.