Kids featured in columns ponder effects of growing up in public

Clarence Dirks moved from urban Seattle to rural Camano Island in the 1940s to farm and write.

From 1946 to 1958, he penned hundreds of newspaper columns for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer about his farming adventures and his two boys, Marty and Mike.

Dirks did Facebook-style writing about his children 50 years before the creation of social media.

Some Facebook users are angry right now about recent changes that allow non-Facebook friends to get information about them. They call the changes an invasion of privacy.

But are these same Facebook writers violating the privacy of their children when they post cute-kid vignettes and photos?

No one yet knows yet what a 25-year-old will think when looking back on a mother’s post about his potty-training mishaps.

Mike Dirks, 65, of Spokane, and Marty Dirks, 77, of West Seattle, grew up with public personas, created by their father and read by thousands of readers. Some of it was fantasy, some reality.

How do the Dirks brothers feel about it now?

The fantasy

Clarence Dirks, a former University of Washington football player and Seattle P-I sportswriter, married Cleo Coons, a college intern at the newspaper, in 1931.

Clarence’s success in the 1930s and ‘40s, freelancing stories to the big magazines of the day, gave him the confidence in 1945 to move his family to Camano Island, about 50 miles north of Seattle, where he intended to write the great American novel.

“Some people can write anything,” Mike remembered. “But my dad could not write a novel to save his soul.”

Mike was born in 1946, a year after the move. Marty, 12 years older, remembers that first year eating “a lot of salmon and clams” because his dad was going broke.

Then, P-I friends urged Clarence to write a column about life as a gentleman farmer.

The column, titled “Diary of a City-Bred Farmer on Puget Sound,” was first published in May 1946. It started as a weekly column but soon grew to five-day-a-week prominence.

Clarence referred to himself as “The Farmer.” The column often wandered from farming to family.

The headline on an Oct. 7, 1946 column read: “Baby’s curls will remain unshorn.” Clarence and Cleo had argued about cutting Mike’s curly locks. Cleo won.

In his March 3, 1947 column, Clarence shared Mike’s first steps: “He trembled, almost lost his balance, caught himself and steadied. As he groped for Farmer’s shirt, Michael took another step.”

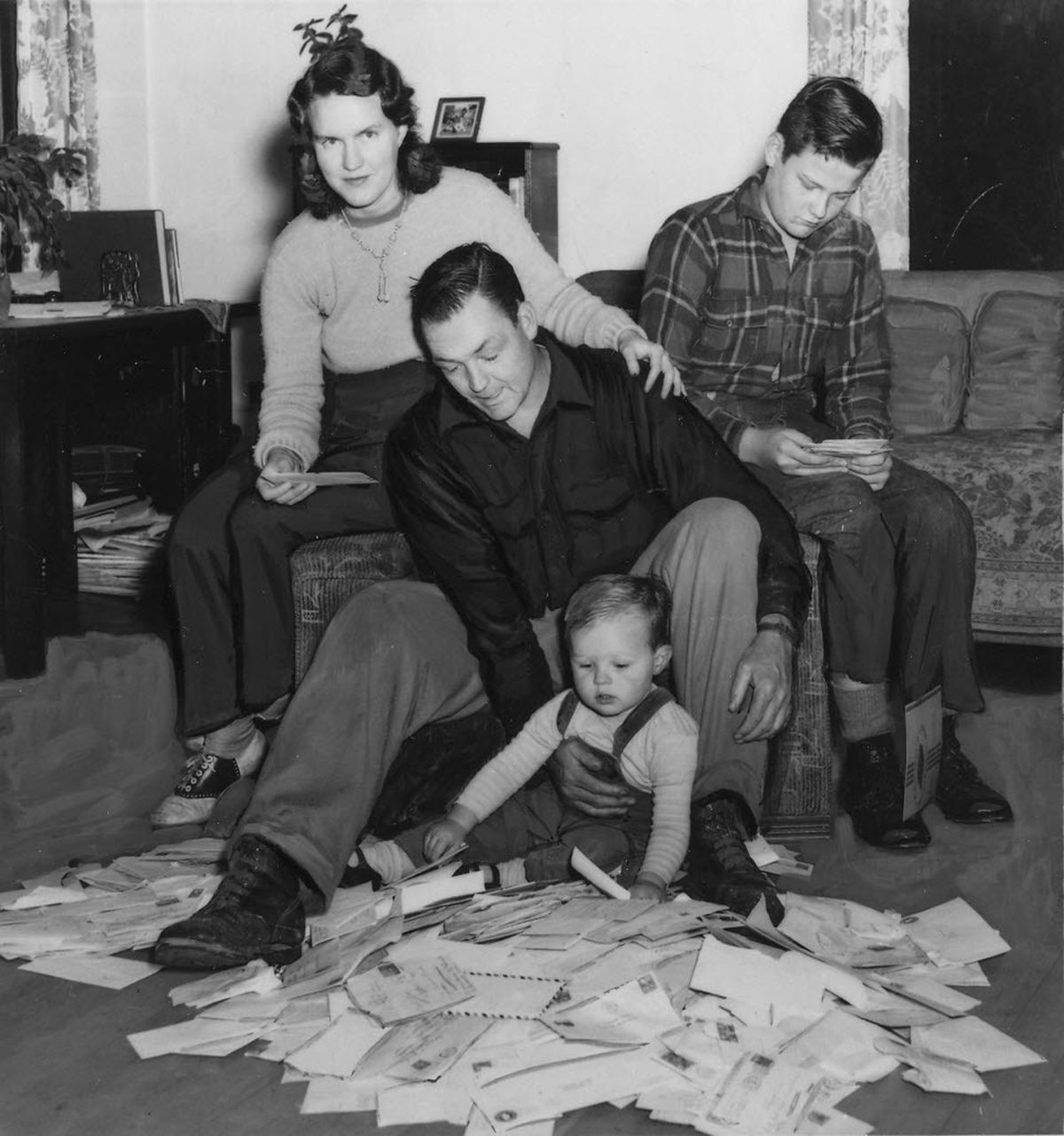

Photos accompanied many of the columns.

When Marty’s heifer, Polly, was named grand champion at a county fair, Clarence’s column about it ran on the P-I’s front page.

The reality

In 1952, Cleo left Clarence and moved to Spokane with Mike, then 6. He didn’t see his dad again for six years. Marty, a high-school senior, stayed on Camano Island.

Before the divorce, Cleo had suffered a nervous breakdown and spent time in a sanitarium.

There was so much tension in the house that the two parents “could have flipped a coin to see who would go for the timeout,” Mike said.

He believes his father’s busyness fueled the tension. Clarence farmed (though not well, his sons says now), wrote his newspaper columns and hosted a farming radio show.

He also raised money for a community church that grew so popular - in part, because he wrote about it - that Billy Graham traveled to Camano Island for the dedication. Clarence later became its minister.

When Cleo and Mike left, “I disappeared from the columns, as did my mom,” Mike said. “The column went downhill. My brother was the only living thing of interest in it.”

And Marty wasn’t crazy about the spotlight.

“In my younger years, it was kind of fun,” Marty said. “Then I got into high school and the column says, ‘Marty ate seven pancakes for breakfast’ and it was embarrassing. You are trying to fit in as a teenager.”

Marty, unlike his father, loved fixing farm machinery and working with animals.

“My dad developed an allergy to cow’s udders,” he said.

The allergy mysteriously disappeared during the fall when Marty was busy with football, his games written about in his father’s columns.

On a few occasions, Clarence even interviewed his son on his radio program.

Marty said: “He’d tell me, ‘You’re a pig farmer and we’ll talk about your farm.’”

Clarence remarried a woman named Ruth within two years of Cleo’s leaving. Clarence called her “Mama” in his columns.

“It was like one wife disappeared and another wife suddenly appeared,” Mike said.

Private lives

The Dirks brothers excelled in college and in their careers. Marty is a retired consulting engineer who still works a few hours each month.

Mike has taught math for 44 years, 25 of them at Spokane Falls Community College. He taught high school before that, in Spokane, Seattle and in Bangkok, where a young Timothy Geithner, now treasury secretary, was one of his students.

Their father died in 1985 at age 82. He continued his busy schedule into old age. He edited a small-town newspaper, wrote for fishing magazines, ran for Congress and lost.

He also returned to ship caulking, the work he did during World War I and World War II in the shipyards.

Mike reconnected with his father as a teen and when he was a student at the University of Washington. He doesn’t remember much of his early life on Camano Island but has met people who do.

“My first day at the University of Washington in 1964, I stood in these (registration) lines for hours. An elderly lady, who looked cross, said, ‘Papers, please.’

“She looks up at me and says: ‘By any chance, are you baby Michael? I used to read all about you.’”

The Dirks brothers remain in awe of their dad’s creativity. Mike has compiled his P-I columns into three bound books.

Both brothers are private people. Both have enjoyed long-term marriages, and children and grandchildren who have done well.

Though familiar with Facebook, neither use it to share family stories.

“People put things up there like they are the center of the universe,” Mike said.